Today in History: “We Hold the Rock”: The Occupation of Alcatraz and the Native American Fight for Sovereignty in the Age of Fracture

Ricard Oakes

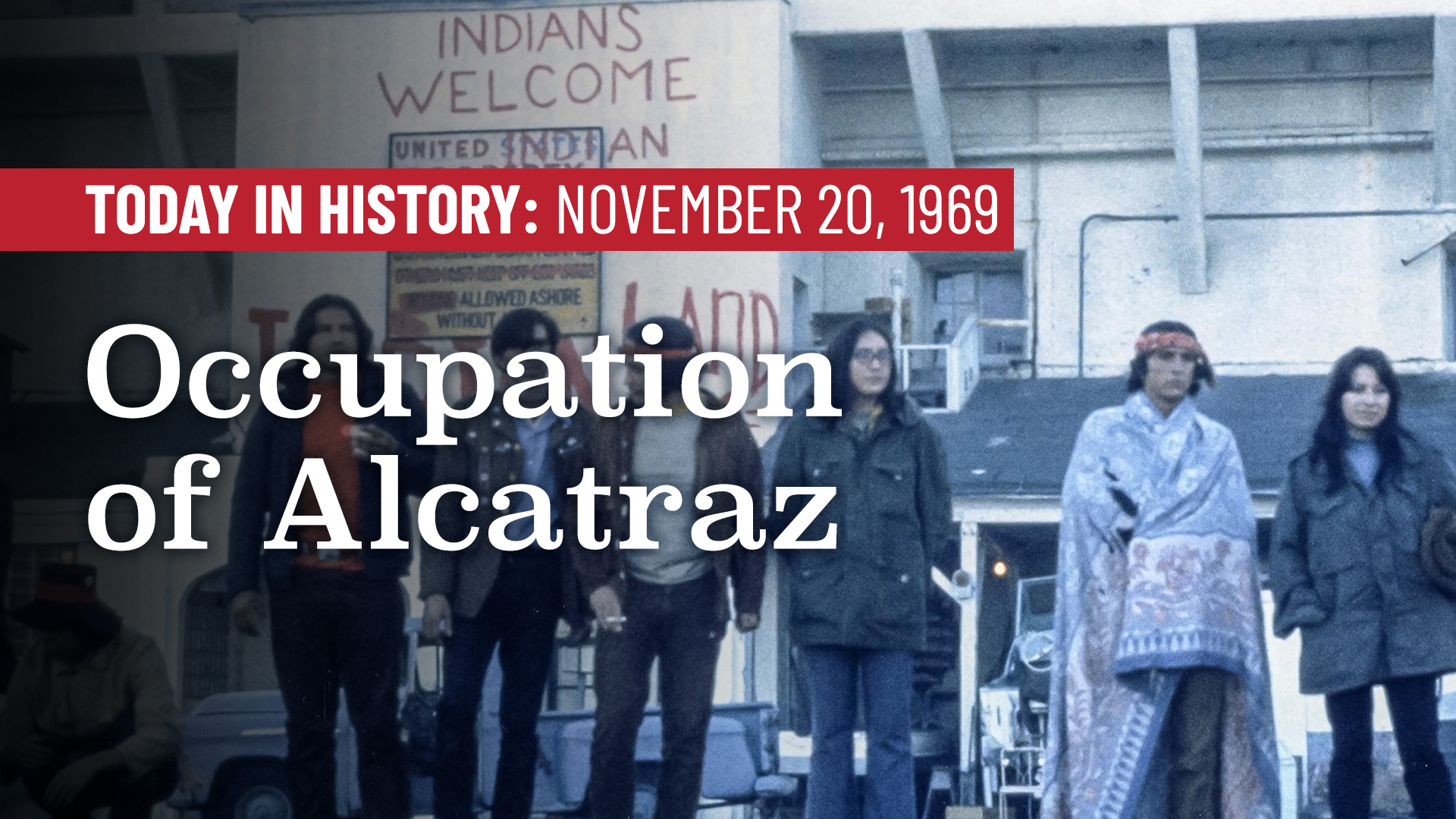

Before Standing Rock, there was the Occupation of Alcatraz, a moment and a movement that has been credited with rediscovering unity among all Native American tribes. Six years after the infamous prison closed its doors, hundreds of Native American activists and students occupied Alcatraz Island for 19 months to raise awareness of continued Native American oppression. Led by two young Native American activists, Richard Oakes and LaNada War Jack, the protesters took over the island, also known as “The Rock,” early in the morning of November 20, 1969. Oakes, a Mohawk student, and War Jack of the Shoshone Bannock Tribes, have since emerged as two central figures in twentieth and twenty-first century Native American activism.

The protest ended in defeat in June, 1971, but the occupation galvanized a movement. Recognized today as one of most important events in recent Native American history, it focused the nation’s attention on the injustices endured by native peoples and ushered in new federal policies and proposals supporting tribal self rule.

For the 52nd anniversary and in honor of Native American Heritage Month, I spoke with Mark Charles, co-author of the award-winning book, Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing, Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery. Charles, a speaker, writer, and consultant who recently moved to Washington DC from the Navajo Reservation, ran as an independent candidate for President of the United States in 2020. He is currently advocating for a Truth and Conciliation Commission – a formal and national dialogue on issues of race, gender, and class.

This interview was primarily conducted on the ancestral lands of the Manahoac, Nacotchtank (Anacostan) and Piscataway people, and was edited and condensed for clarity. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

Charles Chavis: Tell us about your childhood and your upbringing.

Mark Charles: I am the son of Theodore and Eveline Charles. My mother’s American of Dutch Heritage. My father is Navajo. I was born at a mission complex run by the Christian Reformed Church in New Mexico. It was founded in the early 1900s as a school hospital and church and operated for nearly seventy years as a boarding school for Native children.

I went to college at UCLA, and I like to tell people that that’s where I kind of began to own my faith and to explore some of my native identity. I frequently refer to myself as a dual citizen of the United States and the Navajo Nation.

CC: How did this experience returning to the Navajo Nation inform your understanding of the Native American experience?

MC: It feels like our native communities are this old grandmother who had a very large and very beautiful house years ago. Some people came into our house, and they locked us upstairs in the bedroom. Today, our house is full of people. They’re sitting on our furniture. They’re eating our food. They’re having a party inside our house. But the thing that hurts us the most, that causes us the most pain, is that virtually nobody from this party ever comes upstairs, seeks out the grandmother in the bedroom, sits down next to her on the bed, takes her hand and simply says, “Thank you. Thank you for letting us be in your house.”

CC: When did you first learn about the Occupation of Alcatraz?

MC: I don’t remember the first time. You read interviews with people who were alive during that era, and they will talk about how this became an almost mythological thing. It was a very, very big event, and it really sparked a lot of peoples’ imagination and that doesn’t surprise me for a moment. When you look at the period of history when that took place, we were right in the middle of the determination era of the United States for Native Americans.

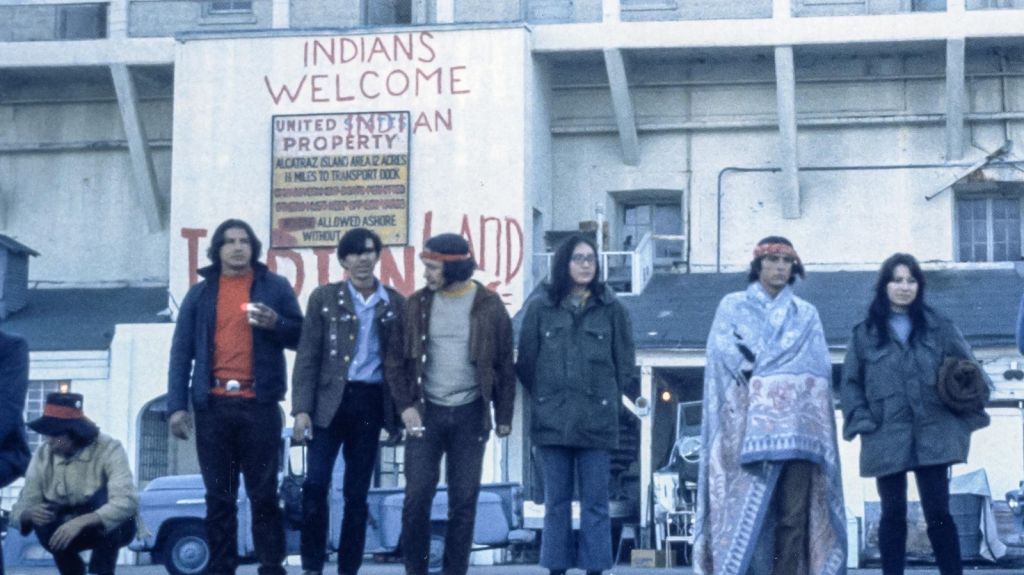

Occupiers standing on the dock at Alcatraz, 1969.

CC: The Self Determination Era began in the late 1960s when Native American Activists began to force the United States to confront its history of mistreatment toward Native Americans. While the Occupation of Alcatraz was part of that movement, a fire that destroyed San Francisco’s American Indian Center was a pivotal event leading up to the occupation.

MC: After the burning of the Indian Center in San Francisco, Richard Oakes and others had the idea of occupying Alcatraz Island, as it was unused federal land. They didn’t go there only for a period of a protest. Native Americans went there to establish this new community. They went there to create a space that they could literally begin to call their own, and they were trying to do it in a very open way of this isn’t just one tribe. The occupation was not in response to one broken treaty or one native nation’s plight. This was really about all of the Indian country.

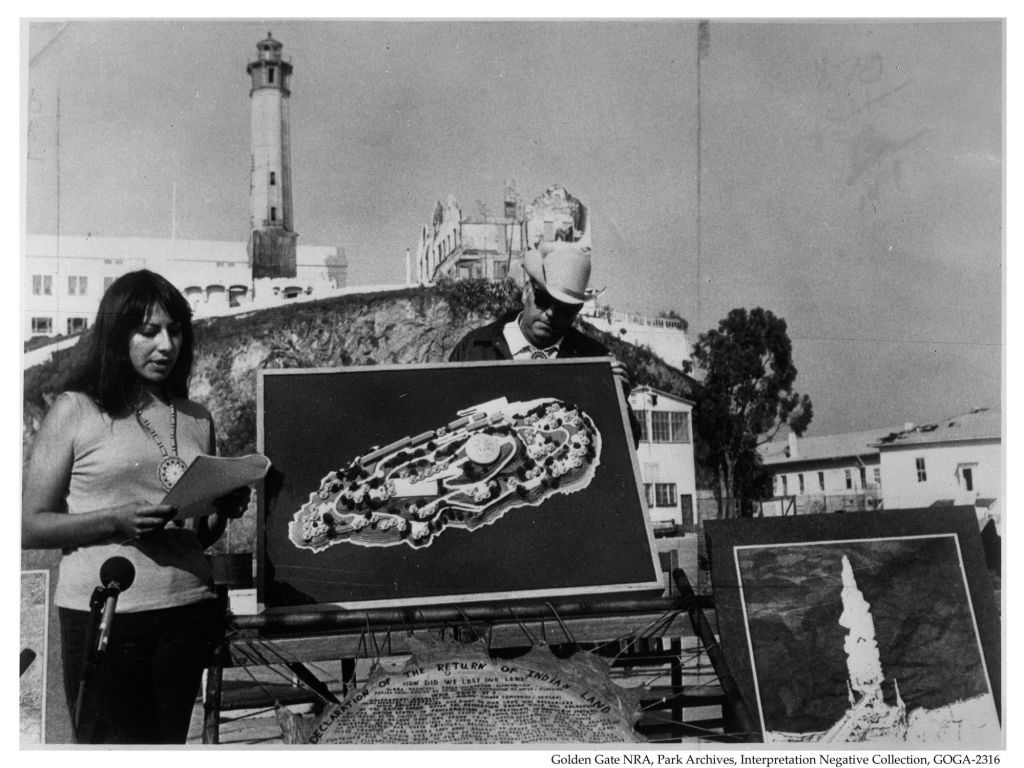

At a press conference celebrating the one year anniversary of the occupation, LaNada War Jack presents an architectural model and blueprint for the creation of a “$6 million tuition free university,” by the Indians All Tribes

“This was really about all of the Indian countries and all of the native nations and it was open to all that wanted to go…..”

CC: Charles Oakes and LaNada War Jack, the leaders behind the occupation, represent a long legacy of overlooked Native American activists, where do you see yourself in this legacy?

MC: The more I’ve learned about the leaders of that occupation, the greater my respect is for them. They were not only trying to counter the reality that was thrust upon them. But they were committed to doing this non-violently, to bring transformational change through nonviolent means. It’s so easy when you’re fighting on the side of the marginalized when you’re fighting from a position of being among the oppressed to allow your anger, your frustration to turn into hate or even violence. They were unarmed. They were trying to really do something very, very positive. That’s definitely a legacy that I want to be a part of, a legacy I want to help leave behind, and it’s something I’m working very hard to do.

“We actually have something that our colonizers can’t steal, they can’t take, they can’t commandeer, they can’t even buy it, which is legitimacy in these lands.”

Mark Charles | Courtesy of Mark Charles

CC: What is your message for current and future Native American activists as they continue to fight for freedom and justice?

MC: We are the host people of this land, and we have to step into our role as the host. This is where I tell our native peoples: We actually have something that our colonizers can’t steal, they can’t take, they can’t commandeer, they can’t even buy it, which is legitimacy in these lands. They tried to conquer, they tried to colonize, and we’re still here.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.