Today in History: Who Tells Our Stories?

“The material spoke of a lost world and lost hope. It is recalled now for Today in History to explore how the past ever shapes the present and how preserving memory is essential in a world that remains no stranger to atrocities.”

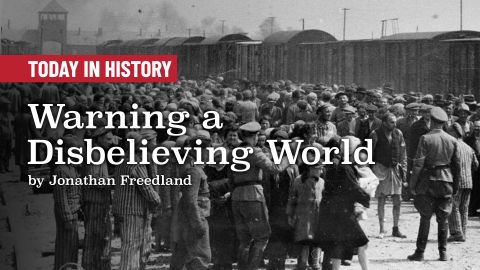

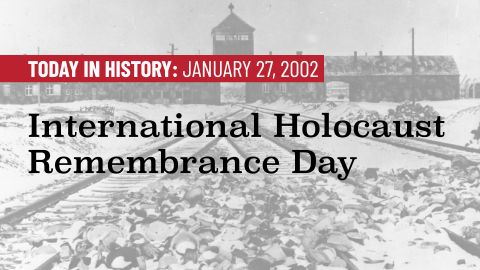

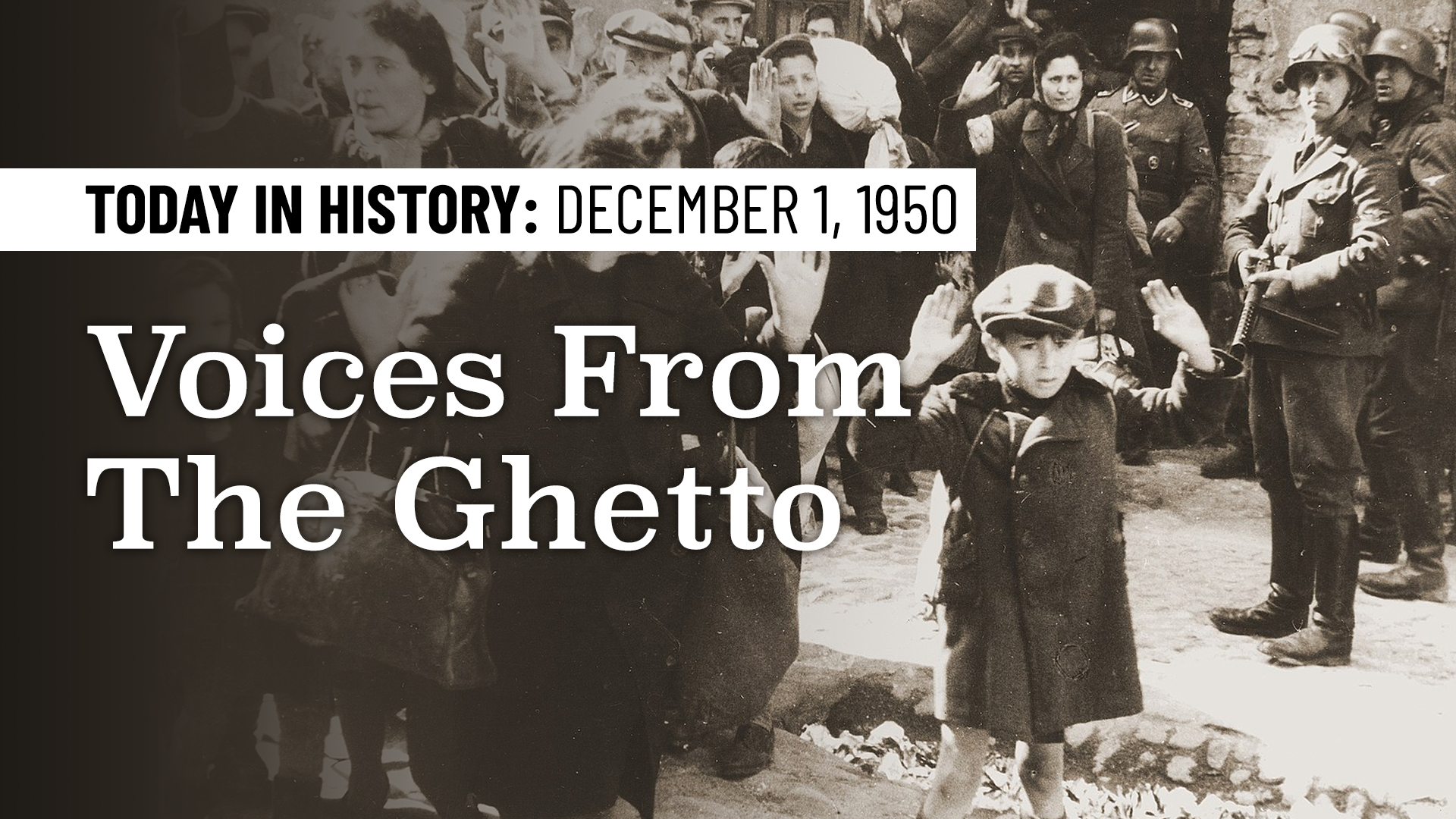

Amid the mass death that defined the Warsaw Ghetto under Nazi oppression, memory managed to survive. Its oxygen was bearing witness, in good measure thanks to a historian named Emanuel Ringelblum. In the first years of the 1940s, Ringelblum organized the collection of thousands of artifacts and written observations that recorded Nazi Germany’s methodical annihilation of Polish Jewry – an archive, he wrote in a diary, intended to “present the whole truth, however painful it might be.”

The pain was undeniable. After invading Poland in September 1939, the Germans forced nearly half a million Jews into the ghetto, an area of 1.3 square miles with a population density five times that of today’s Manhattan, the most thickly populated county in the United States. Conditions there were unbearable. By the spring of 1943, most everyone perished, first from starvation and disease, then – by the hundreds of thousands – in Treblinka, Sobibor and other Nazi death camps.

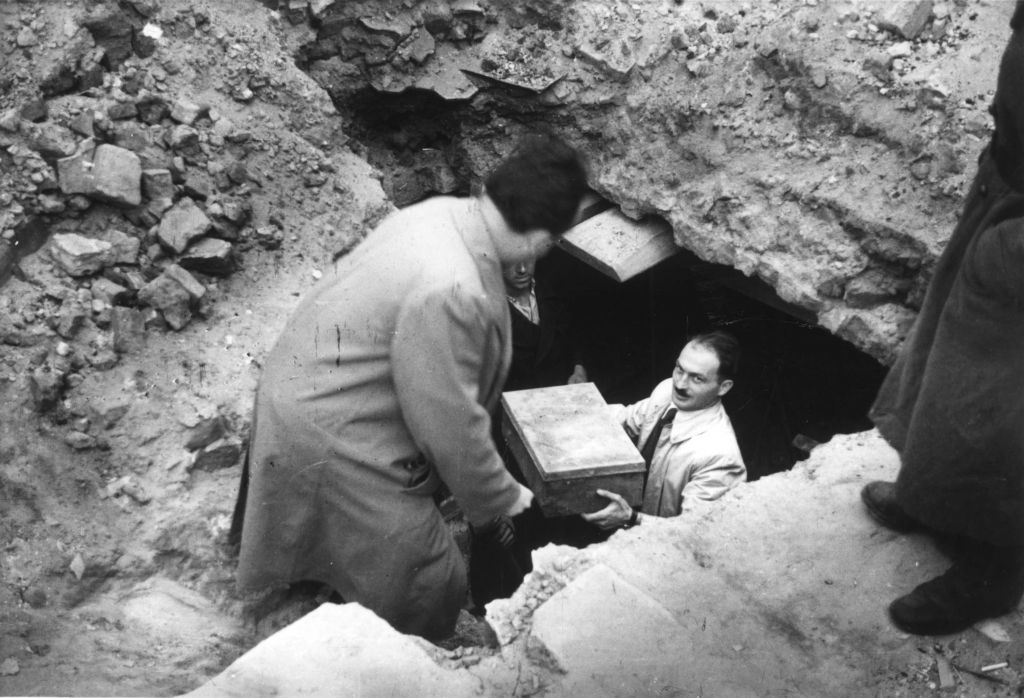

The ghetto itself was demolished. But beneath the rubble, postwar diggers discovered much of what Ringelblum and his team had worked so hard to preserve and had hidden. In September 1946, they found 10 clay-covered tin boxes filled with documents. Then, on December 1, 1950 – exactly 71 years ago – they unearthed two milk cans containing still more matter in the cellar of a collapsed house on Nowolipki Street. A third trove believed to exist has never been found.

The material spoke of a lost world and lost hope. It is recalled now for Today in History to explore how the past ever shapes the present and how preserving memory is essential in a world that remains no stranger to atrocities.

The Warsaw archivists included underground newspapers, eyewitness accounts of ghetto life, wall posters, drawings, poems, official notices, diaries, and mundane items like candy wrappers, ration cards and school assignments. People across the religious and political spectrums were called on to write what they had seen and felt. So were children. There was even dark humor, like a joke about Hitler dying and wondering, upon seeing Jesus in heaven, why he wore no armband identifying him as a Jew. “Let him be,” St. Peter says. “He’s the boss’s son.”

Ringelblum, whose name means “marigold” in German and Yiddish, recruited a cadre of scholars and writers to amass the documents. To report on their progress, they met covertly on Saturday afternoons, the Jewish Sabbath. Thus, the operation came to be called Oyneg Shabbos, in normal times a traditional gathering that can be translated as the Joy of the Sabbath.

What Ringelblum insisted upon was the truth in all its starkness. If possible, various versions of the same events were included in the archive. If some Jews were complicit with Nazi barbarism, that was dutifully noted, as were instances of kindness by Germans and Polish Gentiles.

“Comprehensiveness was the principle of our work,” he said in a diary written in Yiddish. “Objectivity was the second principle.” He further wrote: “Every redundant word, every literary gilding or ornament, provoked our anger. Jewish life in wartime is so rich in tragedies that it is unnecessary to enrich it with one superfluous line.” The goal could not have been plainer: to guarantee “that our suffering remain on record for future generations and for the whole world.”

“There was even dark humor, like a joke about Hitler dying and wondering, upon seeing Jesus in heaven, why he wore no armband identifying him as a Jew. ‘Let him be,’ St. Peter says. ‘He’s the boss’s son.'”

The Oyneg Shabbos project ended in April 1943, with the ghetto in rebellion and Nazi extermination of European Jewry in high gear. Documentation included descriptions of the suffering of Jews in Polish cities other than Warsaw, plus accounts of death camp horrors that had begun to make their way to the ghetto.

With exquisite understatement, Ringelblum wrote that, to his regret, the archive turned out to be less thorough than envisioned: “We lacked the necessary tranquility for a plan of such scope and volume.”

There was, of course, no tranquility in the ghetto. Its Jews staged a valiant but ultimately unsuccessful uprising in the spring of 1943. Of the perhaps 60 members of the Oyneg Shabbos collective, only three survived to the end of World War II in 1945. Ringelblum was not among them.

In March 1943 he escaped with his wife, Yehudit, and their son, Uri, and hid elsewhere in Warsaw. But he made it back to the ghetto in the midst of the uprising, only to then be captured and deported to a Nazi concentration camp in the Polish town of Trawniki. Again, he escaped, and went into hiding with his wife and son. Again, he was found. In March 1944, he at age 43 and his family were shot to death.

The Oyneg Shabbos material is now stored at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, a research foundation created in 1947 and bearing Ringelblum’s name. In 1999, Unesco included the archive in its Memory of the World initiative, a program begun seven years earlier to keep humankind’s documentary heritage from disappearing, whether through deliberate destruction or mere neglect.

And so, in death, Ringelblum prevailed. It was not the Nazis who had the final word about the fate of the Warsaw Ghetto. That belonged to their victims.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.