Today in History: “The Silent Shore”

On November 4th, Mrs. Audrey Jackson Matthews, 93 years old, returned to John Wesley United Methodist Church, the only institution that remains from the Georgetown Neighborhood, a black business district located in Salisbury, Maryland. Ms. Audrey, nursing a foot injury, made her way up the same steps that she remembered climbing as a child. Up for the challenge, she reached for my hand, and I guided her up each step. After a minute or so, she finally made it into the sanctuary.

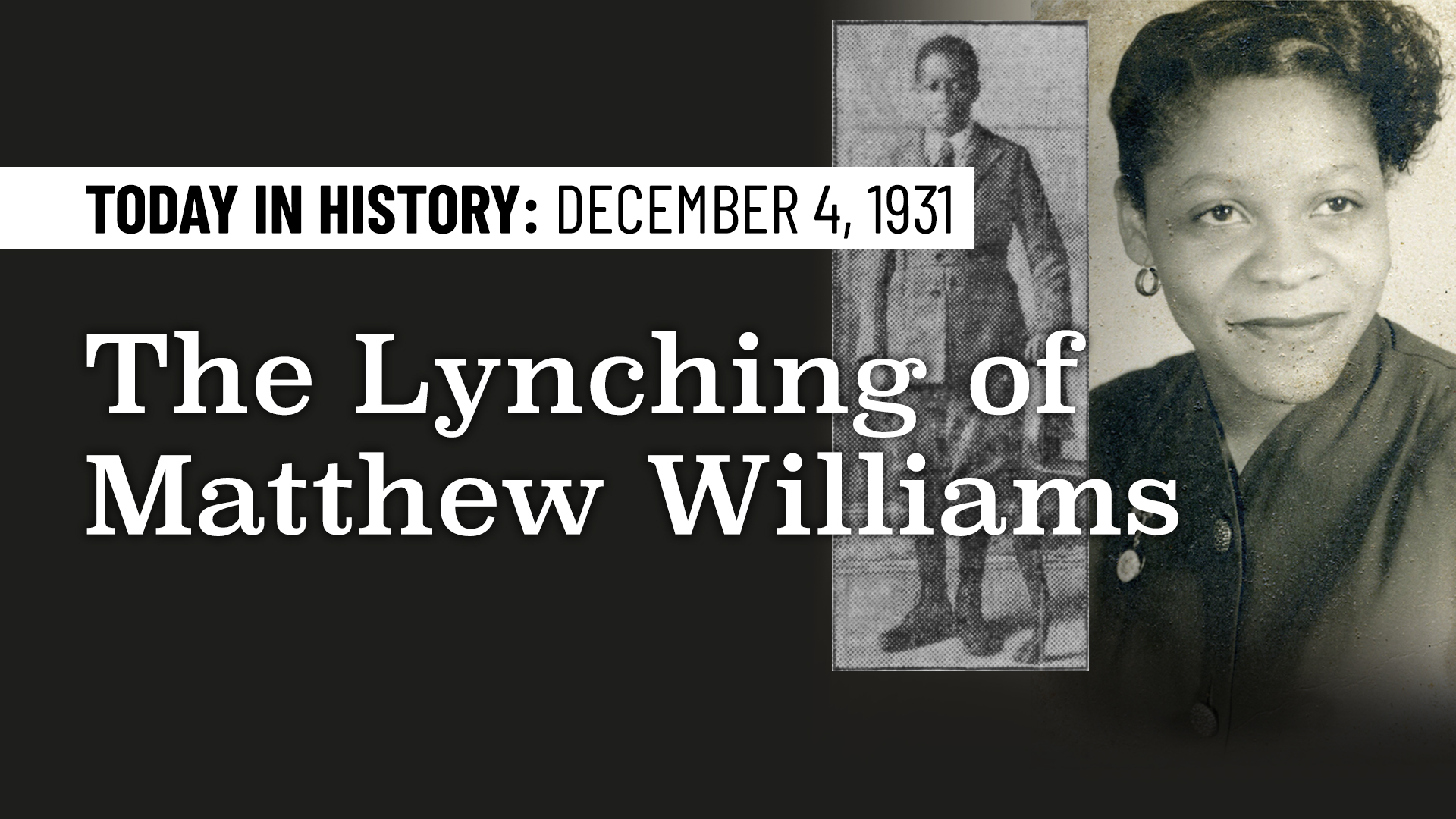

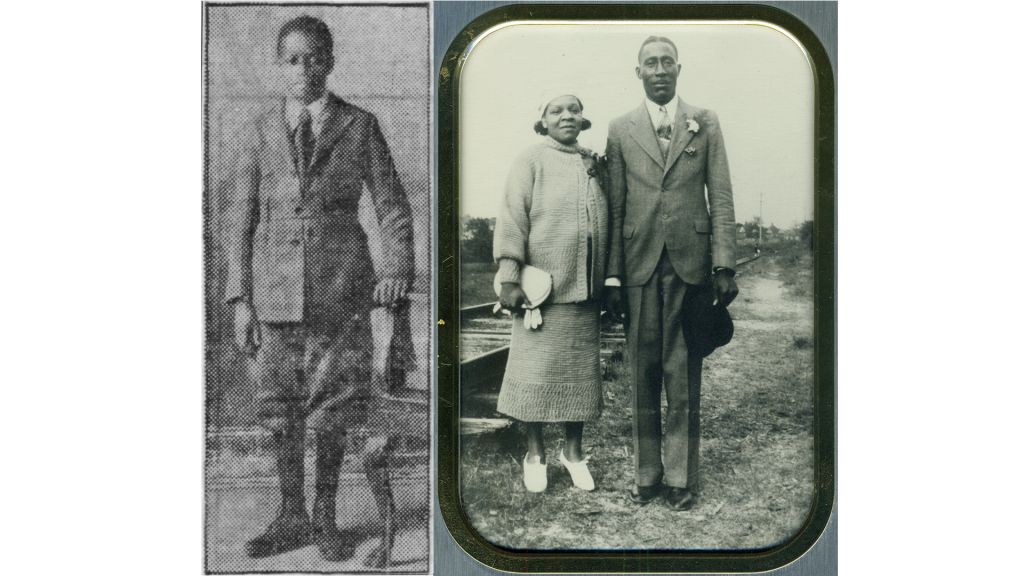

Young Mrs. Audrey “Jackson” Matthews (Circa 1950’s) | Photo Courtesy of Ms. Audrey Matthews and the Charles Chipman Cultural Center.

She is the only one left; all of her friends and family are gone, she has survived them all. However, her community’s memories live on, and upon stepping foot in the sanctuary, she was awakened to their presence. To truly understand what she lived through and the story of her community, we have to travel back in time, back ninety years, when she was only three years old.

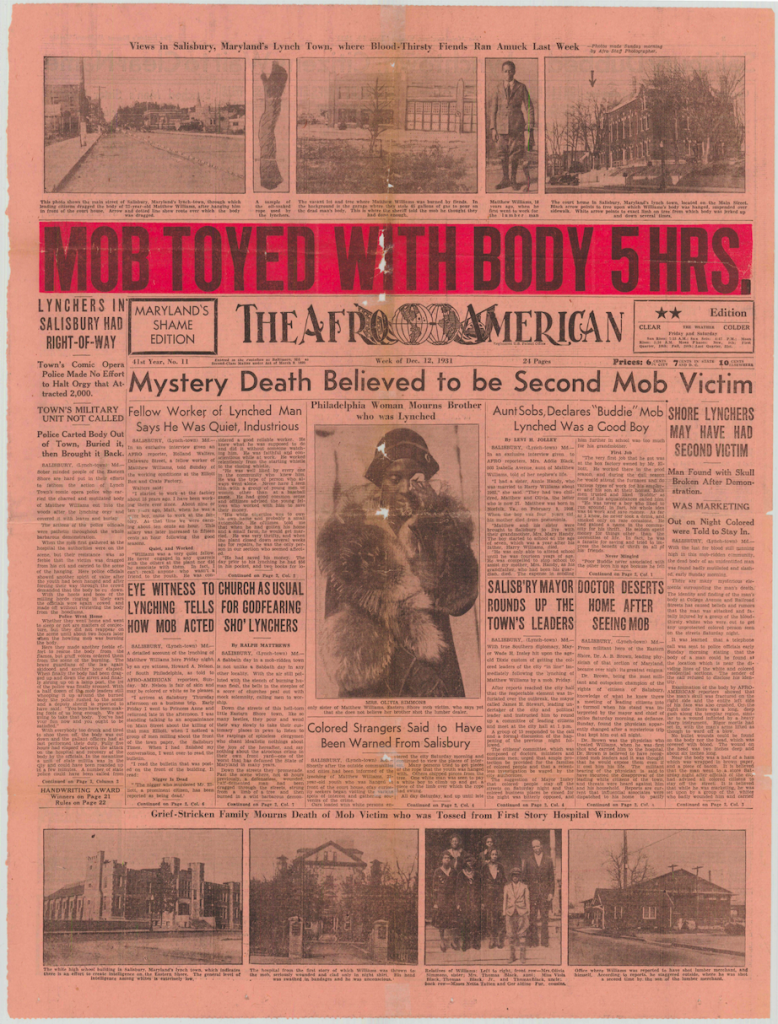

On December 4, 1931, a mob of white men in Salisbury, Maryland, lynched and set ablaze a twenty-three-year-old Black man named Matthew Williams. His gruesome murder was part of a wave of silent white terrorism in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929, which exposed Black laborers to white rage in response to economic anxieties. For nearly a century, the lynching of Matthew Williams has lived in the shadows of the better-known incidents of racial terror in the deep South, haunting both the Eastern Shore and the state of Maryland as a whole.

The story of the lynching of Matthew Williams and the subsequent destruction of the Georgetown Neighborhood of Salisbury, MD is rife with lessons of our racial past. The truth of the story offers potential for restoring and repairing the country to ensure a healthy and vibrant future for Black people.

“Maryland’s Shame Edition exposé on the Lynching of Matthew Williams.” | Source: Baltimore Afro-American, December 12, 1931.

(on left) Matthew Williams, when he first went to work for Daniel “D.J.” Elliott, c. 1915. | (on right) Mr. William and Mrs. Viola Jackson, the parents of Mrs. Audrey Jackson Matthews. (Circa 1930’s) | Photo Courtesy of Ms. Audrey Matthews and the Charles Chipman Cultural Center.

“Everybody had to stay inside, I remember mom and dad telling me we had to stay in the house, you could not go out…during that time Blacks were not seen in the streets.”-Ms. Audrey Matthews

The Story of Matthew Williams

On this day in 1931, following a dispute over pay discrepancies between Matthew Williams, a native of Salisbury, Maryland, and his employer, Daniel Elliot, witnesses heard two shots fired. When authorities arrived, Elliot was dead, and Williams, incapacitated and unconscious, was lying in a pool of blood. Shortly thereafter, Williams was taken to the segregated wing of Peninsula General Hospital located in downtown Salisbury. After discovering that he was alive, a crowd of more than a thousand people demanded that the hospital turn Williams over.

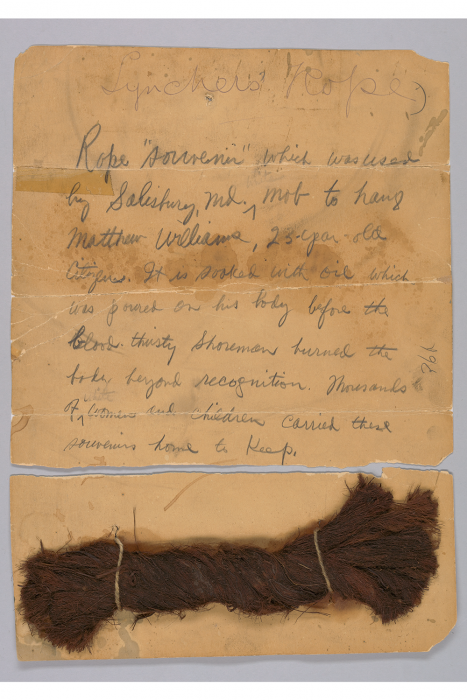

Eventually, the mob reached Williams, who was straight-jacketed in the hospital. Mob members threw him out of the window to the angry crowd below. White thugs including local law enforcement officers then stabbed and dragged Williams three blocks to the courthouse lawn, where they hung his unconscious body twenty-five feet above the ground, with an oil-soaked rope provided by the local fire chief. A piece of that rope now resides in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Handwritten note and rope used to lynch Matthew Williams, December 1931. | Source: Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

Shortly thereafter, onlookers witnessed the traditional conclusion to such a ritual, which historian Donald Mathews names “the southern rite of human sacrifice,” as ruffians cut Williams’ toes from his body as souvenirs. Finally, as if they had not done enough, the white mob anointed Williams’ lifeless corpse with oil and gasoline and set his mutilated body ablaze directly in front of the Georgetown community.

Courthouse yard where Matthew Williams was hanged before his body was burned, c. December 5, 1931. The arrow points to the tree limb from which he was hanged, directly in front of the Wicomico County Courthouse and next door to the city jail. | Collection of Maryland State Archives.

The Georgetown Community

The Black community that Williams and Matthews were part of consisted of two neighborhoods within the city of Salisbury, Maryland — known together as Georgetown. Georgetown, like Greenwood, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Florida was a Black community with businesses, schools, several churches, and a number of residences. Before the lynching of Williams, there were a total of 19 structures. In 1931, following his lynching, a lesser massacre was levied on the entire Black neighborhood of Salisbury, Maryland.

Instead of using direct violence, the white community of Salisbury implemented a government-sponsored land displacement strategy, stripping the Black Community of wealth, financial stability, resources, and educational opportunities. This process was set in motion directly following the lynching and continued into the 21st century. Today, the Black community of Salisbury has yet to recover from this systemic assault. Ms. Audrey Matthews recalls the second phase of this assault when, years later, urban renewal exacerbated pre-existing inequities, and gradually laying waste to the remaining homes and Black businesses in Georgetown. These inequalities gradually undermined Georgetown and other Black communities throughout the United States.

“I didn’t have much of a choice, but to come home one day and go around on popular hill avenue and the house was gone, it was demolished. There was nothing that I could do, but pay for the demolishing of the house, then we would practically give it to them. They paid but it wasn’t what it should have been.”-Ms. Audrey Matthews

Today nothing is left of Williams’ community but the church in which he was raised, John Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1838, five local freedmen purchased the property and built the church. In 1994 it became the Charles H. Chipman Cultural Center and is the only structure left representing a successful Black community.

Charles Chipman Center, only institution of the original Black neighborhood still in existence. | Photo Courtesy of Ms. Audrey Matthews and the Charles Chipman Cultural Center.

For more than five years, guided by descendants of Williams, I have devoted my life to researching and investigating racial terror lynchings on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. As a result of this work, the silence that surrounded Williams’s death has finally been broken. Today, we finally know the story of townspeople who stole a life, terrorized Black residents, destroyed a Black business district, listened to testimony from 124 witnesses to the brutal lynching, and held no one accountable. In a town where silence has persisted for over ninety years, the story of brave descendants and witnesses willing to use the truth to fuel transformative justice is finally coming to the light.

From the lynching of Matthew Williams to the modern-day lynching of Ahmaud Arbery, these unrelenting acts of systemic racial violence have traumatically shaped the identity of Black citizens and communities throughout the United States. My work has joined forces with #breathewithme Revolution and together we have catalyzed an unprecedented national movement of over 300 national organizations and influencers. Seeking to establish a U.S. Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation (TRHT) Commission and implement lasting, transformative policies, our goal is to dismantle the systemic racism that has continually interfered with and injured Black lives, Black communities, Black entrepreneurial endeavors, and Black businesses.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.