Maryland is the first state to formally reckon with its history of lynching and racial violence

Healing wounds over and violence from years past can be an extremely difficult endeavor. South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commission was the most famous attempt of its kind—but now, Maryland is the first U.S. state using the resolution model to reckon with its history of racial violence. Charles Chavis, assistant professor at George Mason University and the vice-chair of Maryland’s truth and reconciliation commission, joins.

Our partners at PBS NewsHour Weekend report on this story.

Read the Full Transcript

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Earlier this year, we reported on a movement to confront historical acts of racial terror in a place you might not expect.

Horrific lynchings occured after the Civil War in the Deep South and the former Confederacy, but also in many border states, including Maryland.

As Special Correspondent Brian Palmer reported, Maryland is now the first state to undertake a formal truth and reconciliation process to reckon with its painful and violent history.

We’ll speak with a historian about that but we begin our update with an excerpt from our June report, which we need to warn you, includes graphic descriptions of violence.

This story is part of our ongoing series “Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and Extremism.”

===STORY ORIGINALLY AIRED IN JUNE 2021===

-

Brian Palmer:

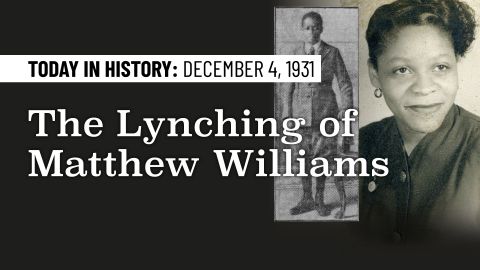

In the center of downtown Salisbury, on Maryland’s eastern shore, the historic Wicomico County courthouse stands today as it did in 1931. Back then this supposed hall of justice was the site of a brutal, extra-judicial killing: the lynching of 23-year-old Matthew Williams. Charles Chavis, Jr.: You know, he was a normal child. I mean, he played with his cousins. He loved going to watch pictures. And during the Depression, he had money in two bank accounts, he had a stable job, was employed and was able to maintain employment. Charles Chavis, Jr. is a historian at George Mason University, and the author of the forthcoming book, “The Silent Shore: The Lynching of Matthew Williams and the Politics of Racism in the Free State.” The horrific lynching of Matthew Williams was reported widely at the time, including in The Afro-American, a Black-owned paper in nearby Baltimore.

While there are differing accounts of what happened that day, what we do know is that Williams worked for a wealthy white business owner in Salisbury. After an altercation, Williams’ boss was dead and Williams himself suffered several gunshot wounds but was still alive.

Once word got out, a white mob formed at the hospital where he had been taken. The nurse in charge of the segregated Black ward reportedly stepped aside to allow his abduction.Charles Chavis, Jr.: There’s a famous quote that’s actually published in The Baltimore Sun where she says, ‘If you’re going to take him, take him quietly.’Brian Palmer: The injured Williams was thrown from a hospital window and dragged several blocks to the courthouse. The white mob tortured, hanged, and then burned his body. The crime was captured in this drawing that ran in the Baltimore Morning Sun.

-

Charles Chavis, Jr.:

Williams was not only lynched on the courthouse lawn, but his body was taken after, you know, when it was burned to the Black section of Salisbury, put on display for onlookers to drive by while the local police department directed traffic.Brian Palmer: No one has ever been held accountable for his killing. Matthew Williams is buried somewhere in this cemetery, his grave unmarked. But after nearly 90 years since the lynching of this Black man, the city of Salisbury is beginning to acknowledge its history of white racial violence.James Yamakawa: When the mob came for him, they faced little resistance.Brian Palmer: On a recent Saturday, a group of several dozen people gathered to retrace the path that the mob took as it dragged Williams to his death, from the hospital where he was kidnapped, still a medical center, across the Wicomico River, to the courthouse lawn,

The occasion was the unveiling of a sign memorializing Williams, an unidentified Black man found beaten to death a day later —and believed to be a victim of the same mob—and Garfield King, an 18-year-old Black man lynched in the county in 1898.

===END OF CLIP===

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Today marks the 90th anniversary of the brutal lynching of Matthew Williams and the anonymous man believed to be a victim of the same white mob in Salisbury, Maryland.

Joining us again is Charles Chavis, assistant professor at George Mason University and the vice-chair of Maryland’s Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission joined us again on the work being done in the state.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Charles, tell me what is the significance? I mean, it’s symbolic, but why the marker in Salisbury? Why is it important?

-

Charles Chavis, Jr.:

These are acts of symbolic reconciliation and we see them as being a first step in a number of steps. They have to take place in order for communities to heal. And in Salisbury, where the Lynching Memorial Taskforce has established this marker, it’s so important that it is right there on the courthouse lawn where the act actually took place.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

I know the state Maryland lynching. Truth and Reconciliation Commission. You’ve started doing public hearings, so to speak. Now you cannot, you can’t retry the case or the crime. You can’t provide justice, so to speak, for the descendants of those people who were lynched. But what are those meetings like or what are you hoping to get from them?

-

Charles Chavis, Jr.:

So the meetings are deeply powerful, not only for those who witness it, but most importantly for the victims, the descendants of the victims in which we’ve had the honor of connecting with and providing them with the space to share their story of their loved ones.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

You went into this process and began researching the death of Matthew Williams, who’s– at the anniversary of the unfortunate anniversary is 90 years ago now. 90 years actually doesn’t seem like that for ago long time ago when we think of the word lynchings.

-

Charles Chavis, Jr.:

I hope that it dispels the myth that these things that lynchings took place at the hands of persons unknown. I titled my book “The Silent Shore,” because this– there’s a myth of silence. What I’m able to uncover in the book is that white members of the community talked about this openly among themselves. We know that this lynching, the lynching of Matthew Williams, like most lynchings, was a state-sanctioned lynching where you had states, attorneys and local law enforcement officers all complicit and culpable in the lynching of Matthew Williams. And there’s still a silence even 90 years later, that is palpable in this community, and it’s very important for us to understand that if we’re going to move forward and break the silence, then the truth has to be validated and we have to make sure that those who are continuing to experience this have their opportunity to speak truth to power. And the one other thing is important to understand Ms. Shannie Shields, who’s a Salisbury activist, she mentions that, you know, one of the reasons why people didn’t speak up is because they worked for the family members of those who were involved. And to this day, some of those family members still hold power over this community, and there’s still that power dynamic at play, which speaks to the continued silence even 90 years later.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Charles Chavis, thanks so much for joining us.

-

Charles Chavis, Jr.:

Thank you so much, Hari, for having me.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

For more, including an essay from Charles Chavis and a new video, please check out the Exploring Hate website, pbs-wnet-preprod.digi-producers.pbs.org/wnet/exploring-hate.

.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Charles, tell me what is the significance? I mean, it’s symbolic, but why the marker in Salisbury? Why is it important?

-

Charles Chavis:

These are acts of symbolic reconciliation and we see them as being a first step in a number of steps. They have to take place in order for communities to heal. And in Salisbury, where the Lynching Memorial Taskforce has established this marker, it’s so important that it is right there on the courthouse lawn where the act actually took place.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

I know the state Maryland lynching. Truth and Reconciliation Commission. You’ve started doing public hearings, so to speak. Now you cannot. You can’t retry the case or the crime. You can’t provide justice, so to speak, for the descendants of those people who were lynched. But what are those meetings like or what are you hoping to get from them?

-

Charles Chavis:

So the meetings are deeply powerful, not only for those who witness it, but most importantly for the victims, the descendants of the victims in which we’ve had the honor of connecting with and providing them with the space to share their story of their loved ones.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

You went into this process and began researching the death of Matthew Williams, who’s at the anniversary of the unfortunate anniversarie is 90 years ago now. 90 years actually doesn’t seem like that for ago long time ago when we think of the word lynchings.

-

Charles Chavis:

I hope that it dispels the myth that these things that lynchings took place at the hands of persons unknown. I titled my book my book The Silent Shore, because this there’s a myth of silence when I’m able to uncover in the book is that white members of the community talked about this openly among themselves. We know that this lynching, the lynching of Matthew Williams, like most lynchings, was a state sanctioned lynching where you had states, attorneys and local law enforcement officers all complicit and culpable in the lynching of Matthew Williams. And there’s still a silence even 90 years later, that is palpable in this community, and it’s very important for us to understand that if we’re going to move forward and break the silence, then the truth has to be validated and we have to make sure that those who are continuing to experience this have their opportunity to speak truth to power. And the one other thing is important to understand Mushiness Shields, who’s a Salisbury activist. She mentions that, you know, one of the reasons why people didn’t speak up is because they worked for the family members of those who were involved. And to this day, some of those family members still hold power over this community, and there’s still that power dynamic at play, which speaks to the continued silence even 90 years later.

-

Hari Sreenivasan:

Charles Chavis, thanks so much for joining us.

-

Charles Chavis:

Thank you so much for having me.