Today in History: Reading the Holocaust 77 Years After the Liberation of Auschwitz

In an article that has been frequently reprinted since it appeared in The New York Times Magazine in 1958, A.M. Rosenthal wrote, “There is no news to report from Auschwitz.” He visited the concentration camp soon after being named bureau chief in Warsaw, 13 years after Auschwitz was liberated. There were children playing near the gates and the trees were green.

“There is merely the compulsion to write something about it,” he went on, “a compulsion that grows out of a restless feeling that to have visited Auschwitz and then turned away without having said or written anything would somehow be a most grievous act of discourtesy to those who died here.”

As we mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, the 77th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz – as designated by the United Nations in 2005 — there are fewer Holocaust survivors in our midst. But new stories keep unfolding, sometimes in unexpected ways. As a longtime culture editor for a Jewish publication, I receive piles of Holocaust-related books every year. I’m always drawn to the urgent memoirs penned by survivors who have found words to match their suffering and, often, their resilience, and also to other stories that emerge from the shadows, bringing new light.

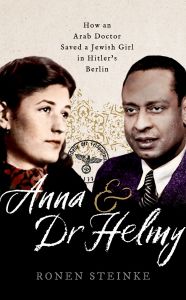

A book published for the first time in English on this anniversary tells a little-known story of a Muslim doctor who risked his life to save Jews, the only Arab to be named “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Israel.

How an Arab Doctor Saved a Jewish Girl in Berlin by Ronen Steinke (Oxford University Press) opens in the autumn of 1943, with the Gestapo charging into the Berlin office of Dr. Mohamed Helmy – a German-trained doctor born in Egypt – and demanding that his headscarf-covered young assistant find her boss. Thanks to the doctor, the young Jewish woman was safe, hiding in plain sight, posing as the doctor’s Muslim niece. From the office, Anna Bolos could hear the trains leaving for Auschwitz. When things became less safe, Dr. Helmy found other places for her to hide and enabled her survival. Aided by a colorful network of Arab and German friends, he also secured safety for members of her family and other Jews.

Anna died in New York in 1986; Dr. Helmy, who married his German fiancé (they weren’t allowed to marry during the war), remained in Berlin and died there in 1982. After the war, Anna and her family visited him twice.

“It is a perception shared by many Muslims in Western countries that the Holocaust has nothing to do with them, that Muslim migrants played no part in that history,” Steinke writes. “This book is evidence to the contrary.”

When Anna & Dr. Helmy was published in Germany in 2017, Steinke, a journalist who grew up in a German-Jewish family in a small town near Nuremberg, did readings around the country. He explains that in many schools, where the Holocaust is part of the curriculum, the large numbers of Muslim children feel alienated. “This helps to include them, to see that their ancestors had a role.” In addition, Steinke participated in community events co-sponsored by synagogues and mosques, including a large event in his hometown, with more than 300 Muslims and Jews.

Carla Gutman Greenspan of New York City, Anna’s daughter, is thrilled that her mother’s story is being told. For her, it’s “a story of hope at a time when there’s so much hatred.”

“If this story could change one person’s mind, it would be good. It’s not just about Muslim-Jewish relations, but about relations between people of all different groups.”

“I’ve always found that human relationships are the most powerful way to combat hatred. You can talk theoretically, but until you really know someone and care about them, you’re not going to be able to lift them up.”

And, stories ignite new stories: Last fall, Rabbi Ariana Capptauber of Beth El Temple in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, whose grandmother and great-grandmother were hidden by a Polish family during the Shoah, took in a family of six Afghan refugees to live in the basement of her home. She sees them almost daily and while they don’t share a language, they communicate through gestures and a translating app; the kids play with her toddler, and the family always invites the rabbi and her family in for tea.

Photo credit: Dan Gleiter of Penn Live

“When you do broad actions, like a protest or educational program, you reach a lot of people a little bit. With something like this, you reach a few people a lot,” she says. “I’ve always found that human relationships are the most powerful way to combat hatred. You can talk theoretically, but until you really know someone and care about them, you’re not going to be able to lift them up.”

This year, Blue Card, an organization assisting Holocaust survivors in need, has partnered with the Turkish Cultural Center to provide a first-ever Holocaust education program for Muslim high school students in New York City.

“This is an important and unique project that will teach students not just about the Holocaust, but the devastating effects of bigotry and hate,” Masha Pearl, executive director of Blue Card, says. “We are teaching youth, our future leaders, about genocide and genocide prevention. Unfortunately, there aren’t many programs across the U.S. that implement Holocaust education in schools — a scary thought as statistics show how little today’s youth know about the Holocaust.”

Aron Krell | Credit: Claims Conference

As Rosenthal understood in 1958, there is an obligation to keep writing, retelling and listening to stories. I was pleased to speak recently with Aron Krell, a 94-year old Holocaust survivor, in advance of this anniversary. For Krell, every day is a remembrance of the Holocaust. He can’t help but see the number tattooed on his left arm when he arrived in Auschwitz in August 1944.

When Krell was 12, he and his mother and brothers were taken from their home to the Lodz ghetto in August 1940. After deportation to Auschwitz, he never saw his mother again. Krell was transported to other camps and liberated in 1945 – the only member of his extended family to survive.

“I can’t forget and I can’t forgive. But I don’t hate.”

After coming to New York, he served in the U.S. Army in Germany and later worked as a waiter for decades. In 2008, he wrote a brief memoir called Overcoming Evil.

“What we went through during the German occupation, there is no comparison. I can’t forget and I can’t forgive,” he says. “But I don’t hate.”

Krell considers himself an optimist. But on this Holocaust Remembrance Day he adds a word of caution.

“Let nobody fool you. I think antisemitism is very serious today. It grows like a cancer.”

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.