Black History Month: “Reflection, Celebration, and Repair”

Four decades ago, Eric Ward says he was a “punk rock kid living in poverty and surviving racism” in Southern California. One day, he was attacked in a hate crime and although it wasn’t the first time he was threatened, it was the first time he “decided not run.” Now, Ward is the Executive Director of Western States Center and a Senior Fellow with Southern Poverty Law Center. Since the 1980s, he has tracked and responded to bigoted violence across the country and established hundreds of anti-hate task forces. In October, 2021, he became the first American to win the prestigious Civil Courage Prize. We asked Eric about his fight for racial justice, inclusive democracy, and what Black History Month means to him.

Our interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

Question: As a racial justice activist, what is the significance of Black History Month to you?

Eric Ward: Black History Month has been around for a long time. It first started the early 1900s as Negro History Week by Carter G. Woodson, an amazing educator. In his book, The Mis-Education of the Negro, Carter G. Woodson lays out an argument that Black history is not simply about the past. It is also a reminder of the living present; an idea that history unfolds around us each and every day. Every action we take is a moment in history, and some of those create big ripples, and some of those create small ripples, but they all create ripples.

And so Black History Month, for me, is a chance to reflect on different ripples in Black history. It’s a time of celebration. It’s a time of remembrance. It’s a reminder to not treat history as some passive thing we observe. Let us get in. Let us mold the clay as individuals and as communities. This is our chance to tell our part of the story.

Q: In describing yourself you’ve said, “the shortest biography is that I am Black in America, carrying what our ancestors got us here to do and trying to prepare for those who come after.”

EW: It’s always important for us to not place ourselves in ways that position us as being an exceptional generation in the Black community. It’s dangerous. It cuts us off from the generational struggle that brought us to this point and it confuses us in believing that it’s our job to complete the journey of liberation or the journey of democracy. That’s impossible. Both are unfolding and unending. And this is our moment to care, take and acknowledge how far we have come and prepare the way for how far we have to go in terms of building a society where we can all live, love, worship, and work free from fear and bigotry.

It’s also important to honor and acknowledge that our ancestors, the generations that came before us, lived under conditions that are unimaginable to us today. If they can move through those conditions, we can move through the conditions we face today.

Q: Borrowing the Jerry Maguire line “you had me at” you made T-shirts and paid a Twitter tribute to 14 Black Americans over 14 days during Black History Month last year.

EW: Please don’t sue me for copyright infringement. But “you had me at” means you won me over as soon as you said these words. And so I made a shirt that just simply said, you had me at, and then it had the name of an African-American leader from the past or present.

Q: Who did you include?

EW: I really wanted to recognize LaTosha Brown, who is one of the co-founders of Black Voters Matter. I think she’s one of the most powerful leaders in this country. She has been working tirelessly around the country, but particularly in the American South, to make sure that black voices are heard. Ella Baker, a great civil rights activist of the 1960s, empowered an entire younger generation. She understood it was important to engage. I gave shout-outs to Rashad Robinson of Color of Change and Glenn Harris of Race Forward. Their belief in the power and the importance of people is without parallel.

All the names on there, every person named, past, present, mentor, I wanted to make sure in that month and on that day, everyone who saw me was also seeing their names. They’ve all influenced me.

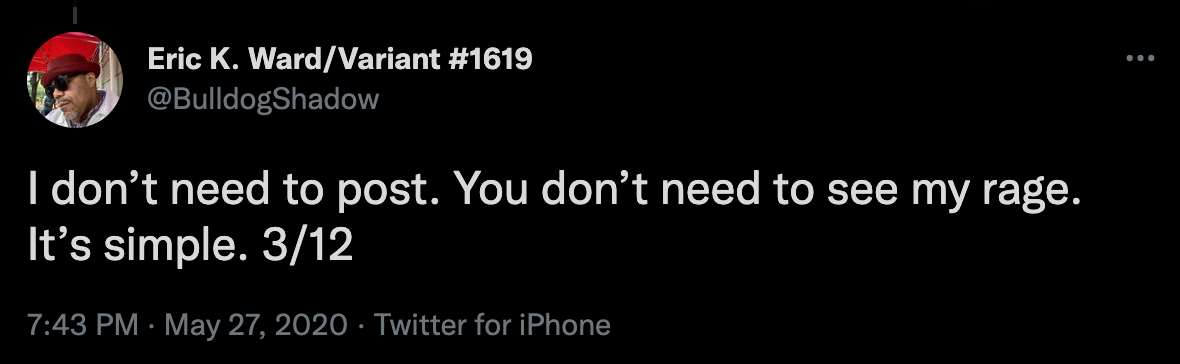

via @BulldogShadow on Twitter

Q: You said that each of them helps you remember a lesson of Black History Month. What is that lesson?

EW: You have to live Black history and you have to live it every day. Don’t let anyone deny you in your community from the opportunity to live history. That’s our choice point. No one can take that away.

Q: You are a prolific writer both long form and on social media. After George Floyd’s murder, you wrote in part: “I haven’t posted publicly about another lynching in America because it’s not my story to tell. It’s not a story of Black and Indigenous America, it’s actually your story and how it is told is all about you. So instead of posting my rage, I choose to stand here in judgment over you, because today, like thousands of Black folks, #GeorgeFloyd no longer can.”

EW: What I meant by that is, what type of society are we, and telling our children we are, that allows a man to put his neck his knee on the neck of another man for nearly nine minutes? While that person is pleading for his life. And no one intervenes. How could you be human and not rage on that day? What type of society would allow that to happen and then attempt to justify it? That is not a society that I can embrace. That is not a society that I can love. That is a society that only gives oxygen to rage. We can’t have a society like that. That is not the way forward. And that is the society I was speaking to in that moment.

In October 2021, Eric Ward became the first American to receive the Civil Courage Prize. Inspired by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, it is awarded by the Train Foundation “to those who fight tyranny as a personal mission and who stand between oppressors and the rest of us.” In his acceptance speech, Ward said: “Having the Civil Courage Prize bestowed to an American for the first time in its 21-year history is both an affirmation of those fighting to preserve and expand our inclusive democracy, and a red flag of how much is at risk.”

Q: What do you mean by inclusive democracy?

EW: Democracy at its core is the idea that all people can come together in a society and work together for the betterment of all. Inclusive democracy is a belief that we can do that as a multiracial society; that we can center people, all people. We can be accountable to all people. It’s the belief of a multiracial America, one that we have been for quite a long time but have never embraced. Inclusive democracy is the democracy that moves us all forward together.

Q: As you reflect this Black History Month, how do you assess where we are?

EW: It’s easy to despair. And we have lots to be concerned about. But we also have to celebrate the victories that have happened. Look, white supremacy is being contested in America. The fact that 25 to 35% of white America believes in a multiracial democracy is astounding to me. How is that possible after being conditioned in this kind of society? That is a sense of resilience and resistance and an embrace of humanity. So I celebrate those things. But here’s the other thing: if you had asked me two years ago if, in 2022, I could sit here and reflect that the vice president is a Black woman. That the current debate, outside of the racists, is not whether a Black woman will be nominated to the Supreme Court, but which Black woman will be nominated to the Supreme Court. In our two political party systems that in one of the parties, the leading most well-known Democrat politico is Stacey Abrams, a Black woman.

I can look all over the country and I can tell you, two years ago, if you had said, Eric, can you imagine that country? I could have told you I would have imagined, but that I would never see it. My dad, who is 96 years old, can’t believe it. But our job now is to try to convince the rest of America, and the way that we convince the rest of America is that we get serious about governance. And we can get there without political violence. We can get there by holding contradiction and disagreeing. We can get there because our children are worth it. And those who came before us are also worth it.

Q: How do you reflect on your personal role in history this Black History Month?

EW: This is a real fight and it’s a heavy fight and it’s hard and it’s scary. I don’t know about future history. I don’t know about my impact. I’m just proud of folks I’ve been able to open up space for. I’m proud of the work that I’ve been able to defend, and I’m proud any time I can help someone stay on the front lines another day

I’m a longtime civil rights activist and most importantly, I’m a Black American. And that means everything for America and everything for myself. It means ultimately I am committed to a multiracial democracy because it is the only place that is home for me. There is no other place for me to go.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.