The following is a production of Tablet Studios in association with The WNET Group’s reporting initiative, Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and Extremism, and with support from Maimonides Fund.

Andrew Lapin: Like so many good mysteries, the story of Father Charles Coughlin’s rapid rise to fame, fortune and influence begins on a train. In 1925, Coughlin was headed back to Detroit from a small town nearby, where he occasionally gave sermons to a flock of farmers who live nowhere near a church and looking around at his fellow passengers. He immediately recognized one of them. That shock of white hair with a dip right in the middle, like the footprint of a giant tidal wave and that large cross dangling down his chest. It was the Most Reverend Michael Gallagher, the bishop of the Diocese of Detroit, a celebrated and beloved priest. He lived in a thirty nine thousand square foot mansion, the largest private residence in the city of Detroit, complete with a massive copper statue of St. Michael the Archangel, defeating Satan. Bishop Gallagher was the man you wanted to know if you were a new priest in town hoping to make a splash. By the time the two reach their destination, young Charles Coughlin charmed his older Superior so much that the bishop was already talking about setting up a new parish. He told Coughlin that he had just returned from France, where he was taken with a new shrine for Saint Therese of Lisieux, known as the Little Flower. Gallagher had an inside track to Pope Pius XI, and he let Coughlin in on a closely guarded secret. Therese was about to become the youngest Catholic saint ever canonized. Royal Oak, Michigan, Gallagher told Coughlin, would be a fine place for the world’s first church, named in honor of Saint Therese. Coughlin didn’t need much convincing. Decades later, long after his fall from grace, Coughlin remembered the moment when his life changed forever.

Charles Coughlin: It was quite a shock to me to find that my bishop had so much reliance on my ability to start a new parish. Michael Gallagher had the dream. I was perhaps the instrumentality of his dream.

Andrew Lapin: Gallagher dreamed of another beautiful church in his diocese, but Father Coughlin had his own American dream, one that went much further. I’m Andrew Lapin and this is Radioactive, an eight part series from Tablet Studios and Exploring Hate about Father Charles Coughlin, the famous radio priest, notorious antisemite, and a man who changed American culture and politics forever. Episode two: The Church and the Celebrity.

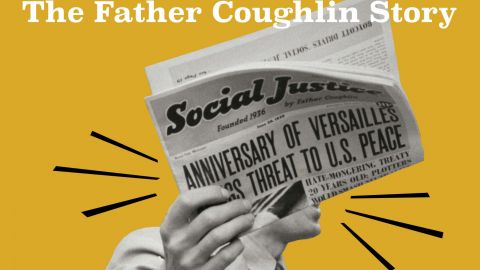

Andrew Lapin: In April of 1926. Father Coughlin put out a notice in the local paper, the Royal Oak Tribune, presenting himself, somewhat dishonestly, as an honors graduate of Toronto University. He announced not only the upcoming church, but also the founding of a national magazine. The times, Father Coughlin understood, were changing. Catholics, long considered a strange and misunderstood minority in vastly Protestant America, were coming into their own and they would need a voice.

Michael Kazin: Well, of course, America was founded unofficially, but definitely as a Protestant nation. Most Americans were Protestants, and Catholics had been the subject of bigotry.

Andrew Lapin: Michael Kazin is a historian of social movements at Georgetown University. He says that Catholics began to gain a toehold in America at the beginning of the 20th century.

Michael Kazin: The mass immigration in the United States from places like Italy and Poland and Hungary, other Catholic nations, in late 19th early 20th centuries. I think the ground was set, if you will, for a Catholic spokesperson for a kind of populism. Coughlin filled that role. He comes out of a Catholic community, which has been the target of bigotry by the Protestant elite, by Protestants, generally throughout much of American history. And yet in different ways, as Catholic community is also beginning to see themselves as part of mainstream America and are really part of the core of the dominant party in the country. They are ready, I think, to sort of claim their place in the American mainstream, and Coughlin exploits that.

Andrew Lapin: But being accepted by Americans was one thing, and building a platform that let you speak to millions of them was another father. Coughlin learned that lesson the hard way when he arrived at the site of his soon to be empire. He told an interviewer years later, “I discovered I had only 28 families, 13 of which were mixed marriages. It wasn’t too bad when the husband was Catholic, when the wife was the Catholic. I couldn’t expect much money.” That meant the most pressing order of business was cash, making a lot of it, and fast, to replace the small brown shingled wooden church with something more befitting of Charles Coughlin’s ambitions. And to raise that kind of money, he knew, he’d have to turn to the one class of people Americans understood to be their secular saints. Celebrities.

Andrew Lapin: Some of the biggest celebrities at the time were on the baseball diamond. The biggest was star slugger for the New York Yankees, Babe Ruth. All time career home run leader, heavy drinker, notorious womanizer and devout Catholic…

Radio announcer: Whose mighty bat was the magnet that drew the crowds. The terror of his major league pitches had won him all that the nation could offer.

Andrew Lapin: One of Coughlin’s friends, Wish Egan, was a scout for the Detroit Tigers, and when the Tigers played the New York Yankees, Egan helped bring the Sultan of Swat to the Shrine of the Little Flower. Here’s Coughlin describing the day.

Charles Coughlin: Well, you can imagine what happened. The Sports page carried it, carried my picture on the Sports page, carried Babe Ruth and all those wonderful players, and here they were at the four doors of the little shingled church that was built here where the cross now stands. Babe was on one side, Wish Egan was at another side, as all the thousands of persons pouring into the church, they were ushered right through one door out the other, and they couldn’t pass without putting some green money in the hats of these Yankees and Tigers. And thus it happened. That over ten thousand dollars was collected by Babe Ruth, who told everybody, “We don’t know how to change money, keep on moving.” And they put it in the bank for me the next day. Well, that’s how the little parish got started.

Andrew Lapin: The Babe’s fundraiser was a stunning success, drawing throngs of people to the church. Coughlin was elated, but his confidence soon faded when he realized that many of those who crowded the pews to see the Bambino smiling and waving weren’t coming back. If he wanted to draw them in, he realized, he would need to become a celebrity himself. How does a Catholic priest from a small, struggling parish outside a big, prosperous city inject himself into the bloodstream of American celebrity? Father Coughlin had an idea. Like many other American cities at the time, Detroit was a hotbed for the Ku Klux Klan. In fact, Charles Boles, the mayor of Detroit for a few months in 1930, counted the Klan among his biggest supporters. In addition to their well-publicized hatred of black people and Jews, the Klan also hated Catholics. Anyone who wasn’t a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant could conceivably find themselves on the hit list of their local Grand Dragon. Coughlin did. As he repeatedly told anyone who would listen, once the local Klan chapter discovered a new Catholic Church was encroaching on their territory, they burned a cross on the front lawn of Coughlin’s small church.

Charles Coughlin: A fiery cross has been planted outside the little finished chapel, and this fiery cross did more than amuse me, I’m telling you, because it was a threat from the Ku Klux Klan, as it was called in those days, that I was not welcome in this territory.

Andrew Lapin: Suddenly, Father Coughlin had precisely the sort of emotional claim he needed, a sure way to pull on the heartstrings of his listeners. He was now a victim of injustice. In a newsreel from 1936, an actor playing Coughlan dramatically rises in the middle of the night to discover the Klan has mounted their fiery cross in front of his beloved shrine.

NEWSREEL ACTRESS: Father Coughlin! Father Coughlin!

NEWSREEL ACTOR: Bigots! Bigots! Bigots! They want a fight? I’ll give them one by radio.. Sermons over the radio from my church! Somehow I’ll get the money to do it!

Andrew Lapin: It was a picture-perfect origin story, so persistent that nearly a century later, in 2012, a Catholic fraternal order dedicated a brand new plaque commemorating the incident outside the building.

Charles Coughlin: I do remember when this cross was put up, that I ventured to say to some of the bystanders and parishioners that one day there’ll be a cross on this corner which neither the Ku Klux Klan nor any other organization will be able to tear down.

Andrew Lapin: Despite the fact that Coughlin told the story repeatedly to the news media and anyone else he encountered, there’s no evidence that the much publicized cross-burning, as reported by the newsreel, actually took place. The local paper, which covered such things pretty closely, wrote about the Klan applying for a parade permit nearby and a couple of automobile accidents a few blocks away. But that’s it. It’s unlikely that something as dramatic as a cross burning would have gone unreported. Father Coughlin wasn’t one to let a few facts get in the way of a great story, and the media narrative now backed him up.

Radio announcer: Father Coughlin’s anger ignites an idea. An idea which he is soon announcing to his little congregation: to combat bigotry and intolerance, he will broadcast his sermons by radio. Out from Royal Oak goes the voice that takes the radio public by storm.

Charles Coughlin: In the five thousand one hundred and ninety nine years of the creation of the world, from the time when God in the beginning created the heaven and the Earth…

Radio announcer: A few years later, over a cornerstone zipped from the Holy Land, rises a new church, dedicated by Father Coughlin’s sympathetic superior Bishop Gallagher, a pretentious million dollar church paid for by his radio audience, a shrine to the political power of Jesus.

Andrew Lapin: This approach worked so well that Coughlin now spoke of cross burnings, plural, as if the entire nation was burning with anti-Catholic hate and only he, Christ’s emissary of love, could douse the flames. As he published in a pamphlet in 1930, “fiery crosses flashed their crimson light upon a peaceful starlit night. It occurred to me that surely no Christian would dare to use the emblem of love and sacrifice and charity to express hatred. Surely there must be some mistake. The whole ghastly affair, the Red Battalion of Fiery Crosses, which blazed from the Gulf of the Great Lakes and from Golden Gate to the Statue of Liberty, must have been lighted not by the torch of faith, but rather by a brand snatched from the hell of ignorance.” Coughlin told his listeners that if you wanted to fight the hellish flames of hate, you needed some serious equipment. So he founded what he called the Radio League of the Little Flower, a membership organization, much like public radio today, that collected fees from listeners across the country to better tell the story of his church.

Radio announcer: Father Coughlin wishes me to thank you in his name, and in the name of all his associates for your loyal support, which is making possible the continuation of these broadcasts throughout the entire summer. May I remind you that this is your broadcast, supported by those who are making sacrifices to preserve Americanism and Christianity in this nation?

Andrew Lapin: Donations started pouring in by the thousands, then tens of thousands, usually just a few dollars at a time. The hard-earned money of working class believers who believed Father Charles Coughlin was fighting for them. Coughlin used that money to build bigger and louder platforms. Now a bit of a celebrity himself, Coughlin spent his days at the Detroit Athletic Club. It was one of the city’s most prestigious venues, designed by the Jewish architect Albert Kahn, although at the time it did not admit Jewish members there. Coughlin could play racquetball and hobnob with the city’s elite: captains of industry, media moguls and war heroes. More than anyone else, he found his people in a group he called, only half in jest, the Evil Four. They were brothers Fred and Lawrence Fisher, who built the bodies for the cars General Motors was putting out and were second only to Henry Ford in the auto industry

Andrew Lapin: That big mansion that Bishop Gallagher lived in? That was paid for by the Fisher brothers. The annual deliveries of the latest model Cadillac to Coughlin’s front door? Also courtesy of the Fisher Brothers. Then there was Dick Richards, the vulgar, charismatic businessman who took the local radio station WJR from the brink of bankruptcy to one of the most successful stations in the country, with a signal so powerful it could be heard all the way in Cleveland. Richards could admire the spectacular views of all of Detroit from his station’s headquarters on the top floor of the Fisher Building.

Radio announcer: Three miles from the river in downtown Detroit stands the Fisher Building, headquarters for WJR. The radio station that is one of a kind.

Andrew Lapin: And there was Eddie Rickenbacker, the World War, one flying ace turned businessman and full time famous person.

Eddie Rickenbacker: Land of Ours America, as I love it…

Andrew Lapin: Rickenbacker was a lifelong believer in the superiority of the white race and a key investor in WJR. They spent their days betting on horses and watching the Detroit Lions football team, which Richards owned. Coughlin took care to dress in civilian clothes whenever he attended any activity not exactly befitting a priest. With the Evil Four in his corner, Father Coughlin could finally see a path to stardom, and it passed through radio.

Neil Verma: This is kind of the beginnings of what we think of as the golden age of radio.

Andrew Lapin: Neil Verma is a radio historian at Northwestern University.

Neil Verma: In the 1920s, the vast majority of this country was rural, and the vast majority of people had almost no electrical implements of any kind. If you want to chart the rise of radio listening across the country, you should chart the rise of electrification across the country because most people the first electrical appliance they ever got was a light. Second was probably in iron, the third was a radio and that became their connection to the outside world. Now, before that, their main connections to the outside world were through their churches.

Andrew Lapin: Radio was like the Wild West in its early days. Anyone could build a transmitter and start broadcasting something. Out in Kansas, for example, a quack doctor named John Brinkley had built the country’s most powerful radio signal and used it to advertise his miracle cure for impotence, surgically inserting a piece of goat testicle into his patient’s scrotum.

Andrew Lapin: The operations made him a millionaire. Clearly, there was a need for regulation, and so the Federal Radio Commission, the predecessor to the FCC, was established in 1927. One of their first orders of business keep propaganda out of broadcasting. Unfortunately, they didn’t get it quite right. Here’s Verma again.

Neil Verma: In 1928, the radio commission passed what’s called General Order 40 and in General Order 40, one of the rules that they set down was that radio stations couldn’t be propaganda stations, so they couldn’t be affiliated with a particular interest group too strongly. That was interpreted to include churches. However, the federal regulators also insisted that every radio station had a public service mandate, and so a lot of local stations interpreted that to mean, including religious content. And so this is the kind of narrow gap in the legislation into which someone like Father Coughlin emerged.

Andrew Lapin: What would it mean for a priest to be on the radio? Was it propaganda or was it public service? No one knew the answer because no one had dared to do it before, nor had any priest ever taken the loan he got from his diocese—a loan traditionally used to build and maintain parishes—and invested it in buying airtime. But Coughlin didn’t care for precedent. The future, he knew, was in being famous on the radio. And so on October 17th, 1926, a full year before the Federal Radio Commission was even established, Father Coughlin stood at the altar of his church and made his first ever radio broadcast. He was not yet 35 and had been preaching at his church for a mere four months.

Charles Coughlin: Jesus Christ, the eternal God and a son of the eternal father willing to consecrate the world by his most merciful coming, being conceived by the Holy Ghost and nine months having had since his conception was born in Bethlehem of Judah of the Virgin Mary made man. Such my friends of the record tally down the ages,

Andrew Lapin: But very soon Coughlin would become the most famous priest, in fact, one of the most famous people in America.

Charles Coughlin: I re-encourage the Christians of America to carry on in this crisis for the preservation of Christianity, and Americanism.

Andrew Lapin: Maybe too famous.

Radio announcer: Unfortunately, Father Coughlin has uttered mistakes of fact and station WMCA wishes to reiterate its position that the views expressed by Father Coughlin on these broadcast are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the station.

Andrew Lapin: Next week: what exactly was Father Coughlin saying on the radio? Radioactive is hosted by me, Andrew Lapin, and is a production of Tablet Studios in association with The WNET Group’s reporting initiative Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism, and Extremism, and with support from Maimonides Fund. The show was produced and edited by Josh Kross and Robert Scaramuccia with Quinn Waller. Our managing producer is Sara Fredman Aeder. Our executive producers are Liel Liebovitz and Stephanie Butnick. Our theme music is from the Ghostwriter and was composed by Alexandre Desplat. All speeches and material of Father Coughlin are authentic to the source, as well as music and other audio from his radio program. This series was recorded at Michigan Radio, Ann Arbor’s NPR Station and WDET, Detroit’s NPR station. Recording engineers at Michigan Radio are Peg Watson and Bob Skon. Recording engineer at WDET is David Leins. Special thanks this episode to Bill Healy, Robin Amer and Penny Lane, director of the documentary Nuts!, for the clip featuring John Brinkley. Please go rate and review us wherever you listen to podcasts. For more information about the show, please visit tabletmag.com/radioactive.

Major funding for Exploring Hate has been provided by: The Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Charlotte and David Ackert, The Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, and Patti Askwith Kenner. For a complete list of funders, please visit pbs.org/exploring hate.