The following is a production of Tablet Studios in association with The WNET Group’s reporting initiative, Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism and Extremism, and with support from Maimonides Fund.

Andrew Lapin: When Father Charles Coughlin first started speaking on the radio, he had one big problem to solve: how he should speak on the radio. It wasn’t like there was anyone he could ask for help. In the fall of 1926, broadcasting was barely six years old. America’s first network, NBC, had just been created. The medium was busy being born, and people were still trying to figure out how to talk to the millions of Americans who were rapidly tuning in. A few months earlier, in January, two white entertainers named Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll hit the air with a ten-minute comedy show playing two bumbling black men. This was radio blackface. It was a horrific stain on American culture. It was also the first ever sitcom. They called it Sam n’ Henry.

Sam n’ Henry tape: Get the most precious diamond in bed now, lets go to sleep, I’m going to turn over here. Come on diamond, get up, get up! I’m alright Sam, I’m alright! You ain’t got no water do you? Ain’t no water?

Andrew Lapin: A few years later, they tweak it a bit, giving radio its biggest hit: Amos n’ Andy. Then in December, folks tuning in to WCCO out of Minneapolis could hear the world’s first ever commercial jingle, asking listeners one searing question:

Wheaties jingle: Have you tried Wheaties? They’re whole wheat with all of the bran. Won’t you try Wheaties for wheat is the best food of man?

Andrew Lapin: There were opera singers on the Atwater Kent Hour. Barking dogs and banjos on the Clicquot Club Eskimos show. And a good swinging time with the Ipana Troubadours. These shows were designed to be fun and designed to sell ginger ale or toothpaste or whatever it was that their corporate sponsors were peddling. Radio was clearly a place for commerce, but could it also be a medium for big ideas? I’m Andrew Lapin and this is Radioactive, an eight part series from Tablet Studios and Exploring Hate about Father Charles Coughlin, the famous radio priest, notorious antisemite, and a man who changed American culture and politics forever.

Episode three: The Sound of America. Radio could sell cereal. But was it big enough to sell God? In 1927, just a few months into his radio career, Father Coughlin took a big bet that the answer was going to be yes. He realized that once people let the radio into their living rooms, they weren’t just going to turn it off after getting a bit of entertainment. Coughlin knew that if he packaged it right, religion could be just as dynamic and popular as a variety hour

Charles Coughlin: Whither goest thou America? Oh, surely not down the highway.

Andrew Lapin: Father Coughlin’s decision to broadcast religious services over the radio was a bold move that became a sensation. Listeners wrote in by the hundreds at first and then the thousands and then the tens of thousands. Some said the preaching on the dial next to Amos n’ Andy was sacrilegious. Others said it was a little crass, but most just wanted more of whatever it was that Father Coughlin was offering. Why? What made him so popular? The writer, Wallace Stegner, had an idea about why everyone wanted to listen to the priest, his voice, a beautiful baritone.

Actor: His range was spectacular. He always began in a low pitch, speaking slowly, gradually increasing in tempo and vehemence, then soaring into high and passionate tones.

Charles Coughlin: If not, my friends, the moment has arrived when we, too, meet Christ, face-to-face. He speaks to all of us, to bring God back into our country. He speaks to all of us to bring back that faith into our hearts.

Andrew Lapin: Coughlin had an instantly familiar voice, one that was often quite pleasant and grandfatherly. He trilled his Rs and dramatically overemphasized his Es, giving his speeches a dramatic flare

Charles Coughlin: These attacks originating with an unprecedented and unsupportable announcement.

Andrew Lapin: Sometimes he even mispronounced words on purpose

Charles Coughlin: …was not the Treaty of Versailles instrumental in removing more than a million milk cows?

Andrew Lapin: Stegner continued:

A voice of such mellow richness, such manly, heartwarming, confidential intimacy, such emotional and ingratiating charm that anyone tuning past it almost automatically returned to hear it again. Warmed by the touch of Irish brogue, it lingered over words and enrich their emotional content.

Charles Coughlin: Those who rejoice in the name of Christians are willing to pledge their talents and their services to Christ! To preserve Americanism and Christianity from attacks originating both from within and without our nation. Christ, the crucified Christ, is a prince of peace!

Actor: It was a voice made for promises.

Andrew Lapin: But what Father Coughlin promised mattered less than how he promised it. Other preachers spoke somberly, their sermons rich with scriptural allusions. Listeners really had to strain to understand the message. That might have worked for congregants sitting in the pews in their Sunday best, but not for the exhausted Americans tuning in while slumped on the couch at home. Those listeners, the masses, needed something simpler and more direct. So Father Coughlin began to develop a method. “First,” he told an interviewer, “I write in my own language the language of a cleric.” And then, “using metaphors the public can grasp, toning the phrases down to the language of the man in the street. Radio must not be high hat. It must be human. Intensely human. It must be simple.” Figuring out what human and simple meant on a brand new medium like radio wasn’t easy. So Father Coughlin turned to a local used car salesman who was notoriously proficient at moving merchandise. Coughlin wagered that selling a priest wouldn’t be that different from selling a car.

Marco Greenberg: There were very tried and true communications techniques that have worked throughout the centuries, and Coughlin was a master of many of those techniques.

Andrew Lapin: Marco Greenberg is a veteran PR executive who has worked with Fortune 100 companies, heads of state and billionaires. He says that Father Coughlin’s radio sermons are a masterclass in the art of messaging and framing, which Coughlin perfected decades before spin doctors and marketing executives made a killing plying the very same craft.

Marco Greenberg: He had command of language that was quotable. That was memorable. That was sticky. And oftentimes that can be a turn of a phrase. Or it can be something with an alliteration, or it can be language that paints a visual picture. But at the end of the day, it catches on.

Andrew Lapin: What did Father Coughlin want? Did he want his listeners to become better Catholics or more devout Christians, or even just better people? Did he want them to attend church more regularly or give more to the poor? That’s what it sounded like he wanted. Here’s what his biographer, Ruth Mugglebee had to say in 1933,

Ruth Mugglebee (actor): He made charity– of understanding of heart and of religious beliefs– the primary motive of his preachings…. He weighed a nation’s sufferings and served religious antidotes for their cure. And throughout it, all there gleamed his hope for universal understanding, the application of charity, sympathy tolerance and the common principles of good and moral living.

Andrew Lapin: In the early years, Coughlin’s show reflected those hopes. He catered his sermons to children, encouraging them to study the Bible. But Father Coughlin, as he’d done since he was a young man, really wanted a bigger stage for himself. The biggest stage, really, which in America meant politics. In 1928, a man named Norman Thomas ran as the Socialist Party’s candidate for president. He was a Presbyterian minister who wore three piece suits, a pacifist who sat out World War One, and spoke eloquently about world peace, and a gifted orator who impressed even his fiercest opponents.

Norman Thomas: We are socialist because we believe we live now in a world that requires a great deal of thoughtful planning ahead of time. We are socialist because we live in a world that is peculiarly interdependent.

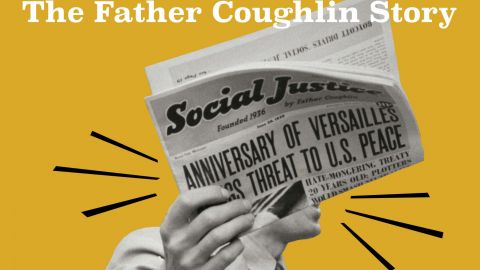

Andrew Lapin: Thomas was a perfect foil for someone like Coughlin, looking to assert himself quickly and forcefully as a player on the political scene. Up until this point, Coughlin’s show had been focused mostly on the Bible and Christian teachings. But when Thomas showed up on the national stage, Coughlin made a hard turn. He decided to use his show as a political platform, not to attack the things Thomas believed, but to go after Thomas himself. So when Coughlin greeted his audience in 1928, he told them Thomas was, quote, “a soft brained radical,” a dangerous lunatic whose aim was, quote, “to have the laboring man declare a war of sabotage against the millionaire.” Coughlin would continue to echo this idea via the radio four years

Charles Coughlin: And you will fall into the trap of Communism. And then what happens? Oh, I am undiplomatic and off the face of a majority of laboring men who love propaganda, which is stirred up by the economy and their fellow travelers.

Andrew Lapin: From that point on, there was no going back. Coughlin’s pulpit was now a lightning rod. Norman Thomas protested, of course. He wrote to Michigan Senator James Couzens to say he was being defamed. And Senator Couzens wrote to Father Coughlin’s radio station and the radio station promised it would curb the preacher’s non-factual attacks on socialists. Here’s Marco Greenberg again.

Marco Greenberg: When we’re talking about Father Coughlin, one of the things that he did, before it was coined, is FUD. The term is fear, uncertainty and doubt. And that was a huge element of why he was successful. It wasn’t simply fear mongering. He did it in a way that was very sophisticated. We see it all the time in political ads when a candidate decides to go negative. Throwing fear, uncertainty and doubt at the subject that you’re talking about can be very effective with the audience, right? They’re not always interested in nuance, in details. They want that emotive punch that they can take home with them and remember that quotable language. And that’s also something that Coughlin did big time.

Andrew Lapin: Coughlin’s controversial brush with Thomas might have been the end of his career if a world historical event hadn’t intervened. On October 29th, 1929, a stock market crash plunged the U.S. into economic ruin, sending more and more people home, jobless, fearing for their future, mistrusting anyone in a position of power and yearning for a savior. America’s fall turned into the radio priest’s rise.

Charles Coughlin: The financial system has played such an important part in closing factories, in creating unemployment, in confiscating homes, in raising taxes and in forcing you to eke out an existence from hand-to-mouth. You have been victimized by an economic system which is unsound, un-Christian and un-American.

Andrew Lapin: Next week, how the Great Depression made Father Coughlin America’s most powerful political kingmaker. Radioactive is hosted by me, Andrew Lapin, and is a production of Tablet Studios in association with The WNET Group’s reporting initiative Exploring Hate: Antisemitism, Racism, and Extremism, and with support from Maimonides Fund. The show was produced and edited by Josh Kross and Robert Scaramuccia with Quinn Waller. Our managing producer is Sara Fredman Aeder. Our executive producers are Liel Leibovitz and Stephanie Butnick. Our theme music is from the Ghostwriter and was composed by Alexandre Desplat. All speeches and material of Father Coughlin are authentic to the source, as well as music and other audio from his radio program. Additional voice acting in this episode by Lauren Lopez and Daniel Strauss. This episode was recorded at Michigan Radio, Ann Arbor’s NPR station. Our recording engineer at Michigan Radio is Peg Watson. Special thanks this episode to Bill Healy. Please go rate and review us wherever you listen to podcasts. For more information about the show, please visit tabletmag.com/radioactive.

Major funding for Exploring Hate has been provided by: The Sylvia A. and Simon B. Poyta Programming Endowment to Fight Antisemitism, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, Charlotte and David Ackert, The Peter G. Peterson and Joan Ganz Cooney Fund, and Patti Askwith Kenner. For a complete list of funders, please visit pbs.org/exploring hate.