Today in History: The Father Coughlin Story

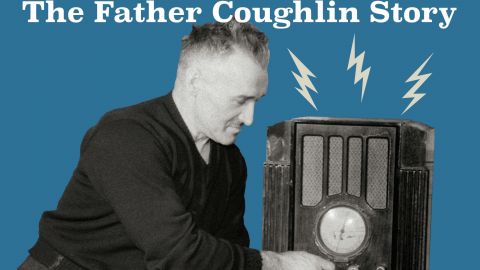

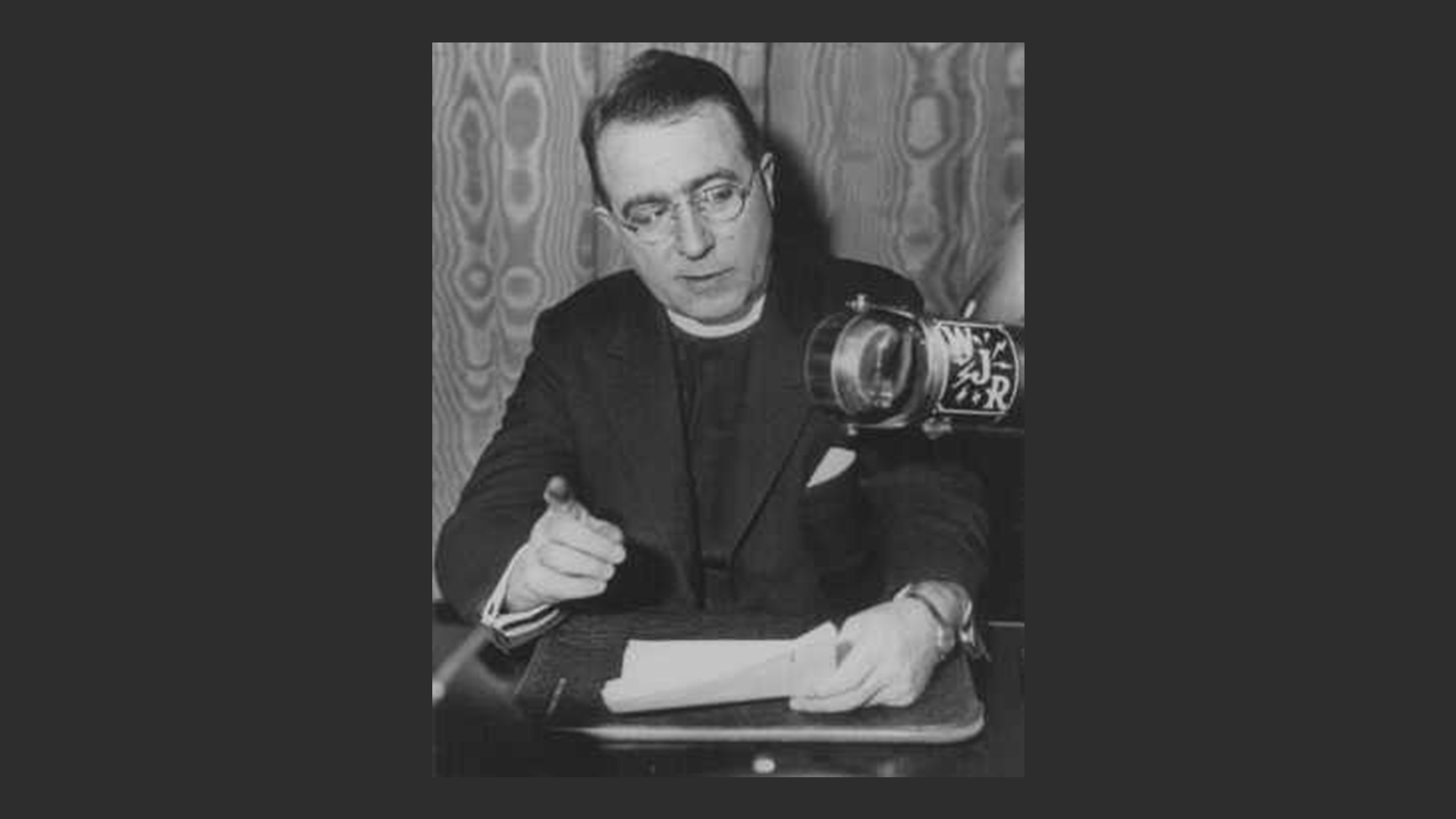

Long before Tucker Carlson’s unvarnished nationalism, before Glenn Beck’s conspiracy theories and Rush Limbaugh’s philippics, Charles Edward Coughlin held millions of American radio listeners in his thrall, playing to their fears while also stoking their prejudices. Make that Father Coughlin, for he was a Roman Catholic cleric. Known as “the radio priest,” he in many ways paved a path for today’s relentless stream of talk-show bluster and televangelism.

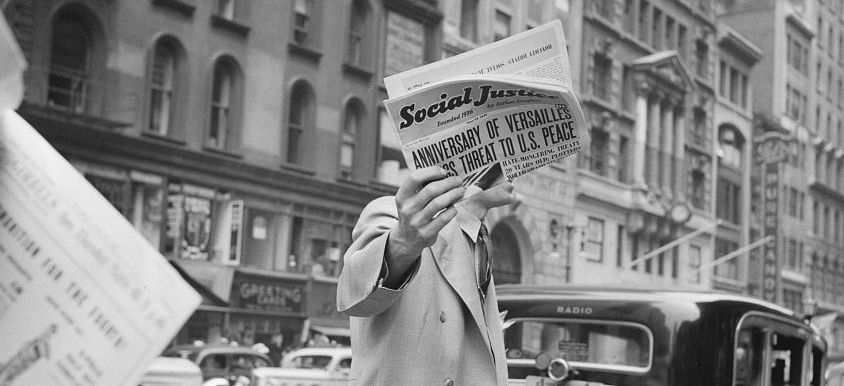

On Sunday afternoons in the 1930s, in a voice rich and vibrant, he addressed an audience so vast that he reached nearly one of every four Americans. Broadcasting from his church, the National Shrine of the Little Flower near Detroit, this Canadian-born priest thundered. He denounced the evils that he saw in both capitalism and socialism. He started out supporting President Franklin D. Roosevelt, newly elected in 1932, then soon turned against him as being “anti-God.” In that Great Depression, he called for nationalizing some natural resources and creating a government-run bank that would control prices and the value of the dollar.

But laced through his sermons and writings, ever more blatantly over time, was an antisemitism that parroted many of the tropes invoked across centuries to persecute Jews.

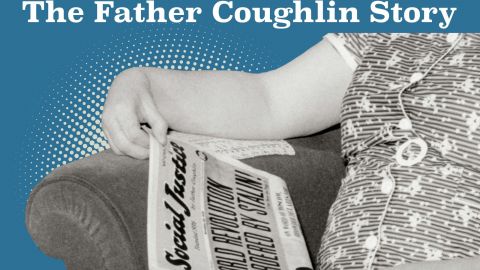

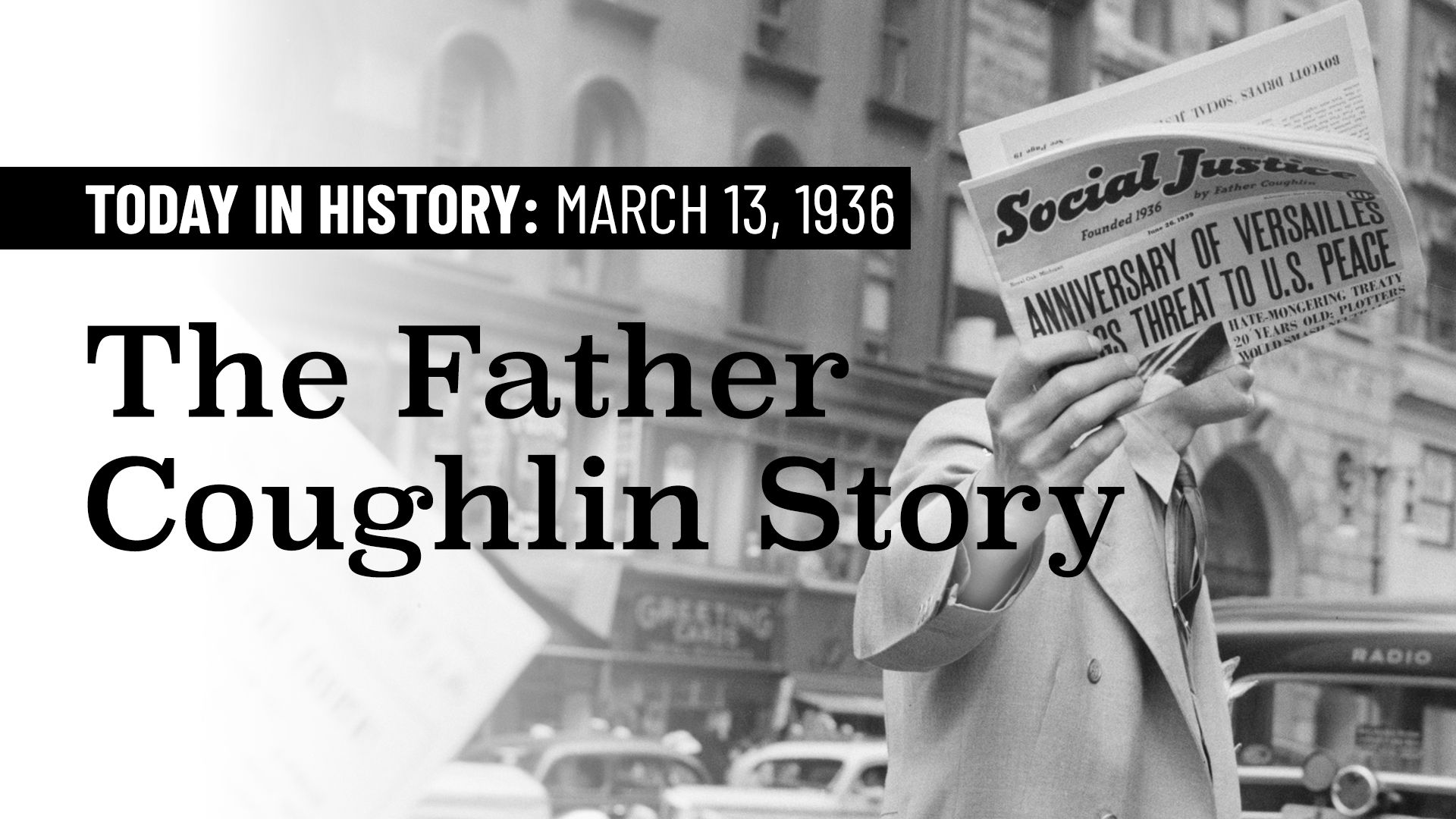

Recalling the huge influence that the priest wielded in the 1930s, The WNET Groups’s Exploring Hate reporting initiative and Tablet Studios launched an eight-part podcast this month called Radioactive: The Father Coughlin Story. March 13 marks a key anniversary in his crusade. On that date in 1936, he began Social Justice, a periodical through which he advanced views that before long put him out of step with American democratic values and with the Catholic hierarchy. By the early 1940s, the church had had enough. It silenced him.

In print and on the air, Father Coughlin (pronounced COG-lin) denounced “modern Shylocks” who had “grown fat and wealthy.” His magazine reprinted portions of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a notorious antisemitic fabrication that described a Jewish plan – nonexistent – for world domination.

“When we get through with the Jews of America, they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing,” he said in 1938. Moreover, “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.” As for democracy, it was “doomed,” he asserted in 1936. “This is our last election. It is fascism or communism. We are at the crossroads. I take the road to fascism.”

Father Coughlin insisted he was not an antisemite, and he distanced himself from detestable groups like the pro-Nazi German-American Bund. Nonetheless, he spoke admiringly of Hitler and Mussolini and also of Huey Long, a homegrown master of demagoguery. He resorted to shopworn phrases in the lexicon of anti-Jewish hatred, with references to “every money changer in Wall Street” and “international bankers.”

Urging the United States to adopt a monetary standard based on silver, he called it “the gentile metal.” And seven months before the start of World War II, he asked, “Must the entire world go to war for 600,000 Jews in Germany who are neither American nor French nor English citizens but citizens of Germany?” Social Justice even carried an article by him with passages that copied a speech delivered by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazis’ chief propagandist. Decades later, in 2004, Philip Roth wrote an essay for The New York Times in which he called Father Coughlin “our nation’s antisemitic propaganda minister.”

Bear in mind radio’s enormous importance back then, with the regulation of the airwaves in its nascence and television, not to mention the internet, beyond most people’s imagination.

At his peak in the ’30s, the radio priest had 30 million listeners, his Sunday broadcasts carried on dozens on stations across America. Bear in mind radio’s enormous importance back then, with the regulation of the airwaves in its nascence and television, not to mention the internet, beyond most people’s imagination. More than 100 clerks were assigned to handle the many thousands of letters that he received each day. For the 1936 election, he even formed his own Union Party, with a North Dakota congressman, William F. Lemke, as its presidential candidate. Father Coughlin predicted Lemke would win 9 million votes. He got fewer than 900,000 in that year’s Roosevelt landslide.

Before too long, Father Coughlin wore out his welcome. Appalled by his diatribes, major radio networks like CBS and NBC dropped him. When the United States entered World War II after the 1941 Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the priest’s commitment to American isolationism and his opposition to American entry into the war became toxic. Invoking the Espionage Act of 1917, the government revoked the second-class mailing permit that Social Justice had enjoyed.

Finally, on May 1, 1942, his superiors in the church ordered him off the airwaves. He obeyed, saying later that “disobedience is a great sin.” He returned to his Michigan church (dubbed “the Shrine of the Little Führer” by some of his enemies) and led it until he retired in 1966. He died in 1979 at age 88. Eleven years earlier, he told an interviewer that he stood by the stances he took in his heyday. Upon being silenced in 1942, he could have resisted, and “the people would have supported me,” he said. “But I didn’t have the heart left, for my church had spoken.”

The radio priest may not be broadly remembered today. Nonetheless, he foreshadowed what was to come on a much larger scale in the broadsides and diatribes that define much of today’s political broadcasting.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

For more about the Radio Priest, Father Coughlin, listen to Radioactive: The Father Coughlin Story: an eight-part podcast about the rise and fall of the first mass media demagogue.