Today in History: Antisemitism, an American Problem

When, if ever, Americans think of antisemitism, they think of the Holocaust. By the time students find their way to my American University course in Holocaust history, they have read The Diary of Anne Frank and Elie Wiesel’s Night. They have seen Schindler’s List and JoJo Rabbit. They have visited Holocaust museums and memorials, many of them in the U.S. They know what antisemitism is. It is the Holocaust.

This focus on the Holocaust gets Americans off the hook. It stakes out a claim that antisemitism is a problem that happened a long time ago in Europe. It implies that the antisemitism erupting in America recently is a new phenomenon. It suggests that the white nationalists, brandishing semiautomatic rifles and chanting “Sieg Heil” as they paraded past a Charlottesville synagogue in August 2017 have no precedent, nor did the murders of Jews at prayer in Pittsburgh and Poway, CA, nor did the hostage taking during services in January at a synagogue in Colleyville, TX.

But these attacks were not the first on Jews on American soil. Sixty-four years ago today, on March 16, 1958, a Miami synagogue and a Jewish community center in Nashville were bombed.

At 2:30 am, under the cover of night, dynamite blasted the school annex of Miami’s Temple Beth El. It tore a gaping hole in the rear wall and hurled a chunk of iron railing onto the roof of a house more than a hundred yards away. Windows shattered and lamps toppled in nearby homes shaken by the blast. Eight hours later, in broad daylight, someone, leaning out of a car rolling past another Miami synagogue, shouted: “You’re next!”

That evening at 8:07 pm, an explosion rocked the car of two detectives parked not far from Nashville’s Jewish Community Center. Earlier, the center had been filled with families and boisterous children attending clubs and activities. Now the empty building had been bombed.

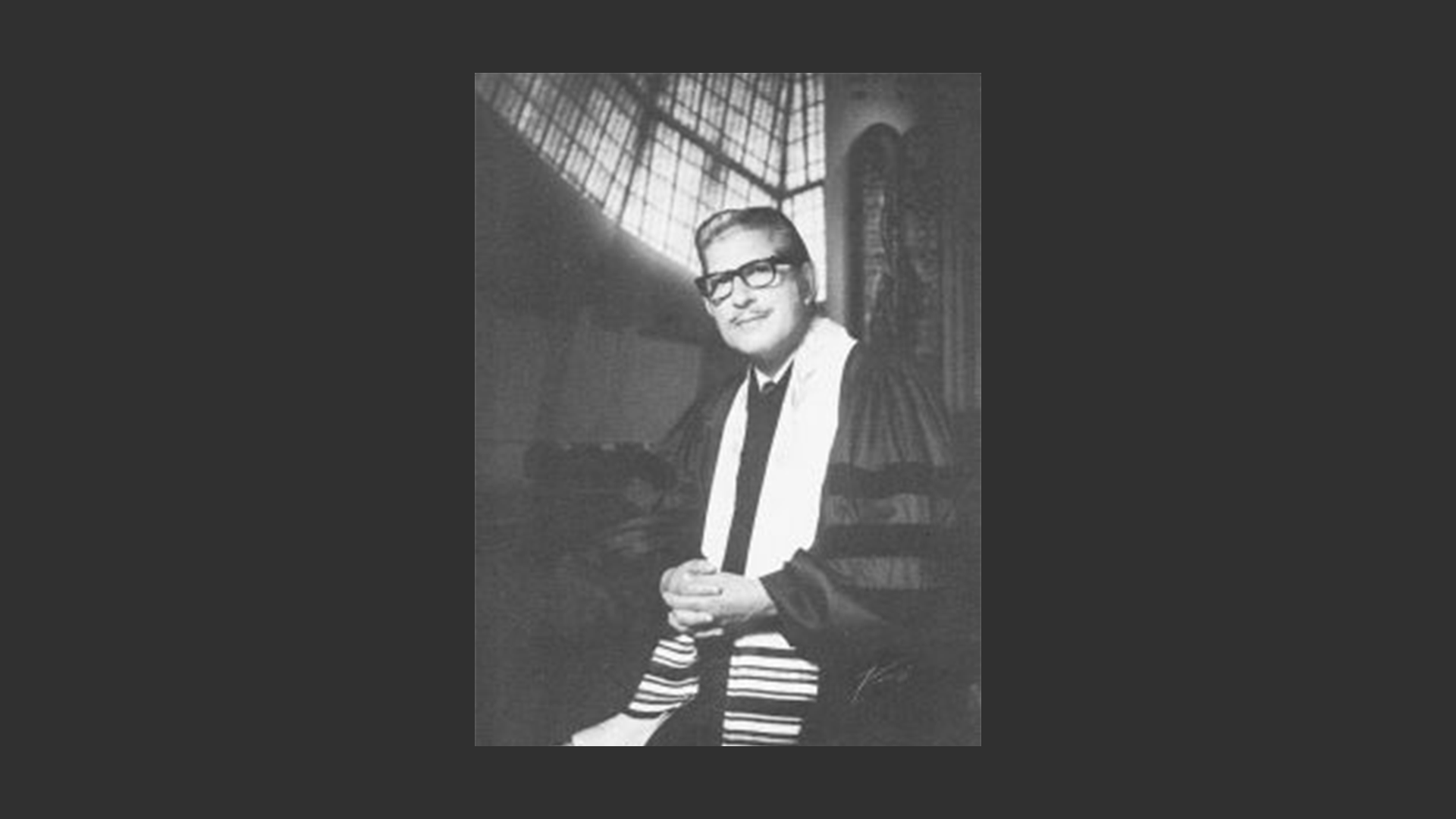

Twenty minutes later, as crowds gathered at the scene, the phone rang in the home of William Silverman, rabbi of Nashville’s Temple. His wife Pearl answered. A “member of the Confederate Union” bragged: “We have just dynamited the Jewish Community Center. Next will be the Temple and next will be any other n****-loving place or n****-loving person in Nashville. And we’re going to shoot down Judge Miller in cold blood,” referring to the judge whose rulings had enforced desegregation in the city’s schools.

Two days after the bombings, Nashville’s daily The Tennessean denounced “Kasperism.” Its editors were referring to John Kasper, whose 1956 rants against integration at a Tennessee high school had sparked a three-day riot quelled only by the National Guard. Sentenced to a year in jail, he was released in time for the FBI to instruct its agents to find out where he was during the October 12, 1958 bombing of Atlanta’s Peachtree Street Temple.

“Rage against Jews was fundamental to the opponents of the civil rights movement.”

Assaults on Jewish institutions in the South came from vigilantes fighting integration, many, like John Kasper, members of the resurgent Ku Klux Klan. Americans rightly remember the terrorism of these years against African-Americans, their homes, churches, and schools: the horrific brutality of fourteen-year old Emmett Till’s murder, the 1963 bombing of Birmingham, Alabama’s 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls. They were but two of the myriad crimes perpetrated against African-Americans meant to break the civil rights movement. As for attacks on Jewish synagogues, community centers, and even rabbis’ homes, these events have left little footprint in American memory.

Yet rage against Jews was fundamental to the opponents of the civil rights movement. Writing of the bombing in Miami, the Anti-Defamation League’s Nathan Perlmutter underscored how racists were convinced that African-Americans were utterly “incapable” of orchestrating the social revolution underway. Only Jews could mastermind that. Perlmutter had witnessed this antisemitism first hand at a KKK rally in northern Florida. There, flanked by giant burning crosses, Kasper had spewed his venom. The crowd thronging the stage cheered and those watching from their cars honked their horns as he ranted against African-Americans. But they gave their loudest cheers and longest honks whenever he targeted the Jews, a people “white on the outside and black inside,” who had to be expressly demoted to “second-class citizens.”

More often, American antisemitism has not turned violent, but that does not mean that it has not persisted. When the very first Jews landed in New Amsterdam in 1654, the colony’s governor Peter Stuyvesant tried to expel them. Calumnies about Jews and money made it difficult for nineteenth-century Jewish businessmen to get credit. The twentieth-century automobile magnate Henry Ford introduced The Protocols of the Elders of Zion with its wild conspiracy theories about Jews’ plotting to control the world. In 1922, when Harvard University President A. Lawrence Lowell justified establishing quotas on the admission of Jews as a way to mitigate antisemitism, the story appeared on the front page of the New York Times.

“This focus on the Holocaust gets Americans off the hook. It stakes out a claim that antisemitism is a problem that happened a long time ago in Europe. It implies that the antisemitism erupting in America recently is a new phenomenon.”

Antisemitism is part of this nation’s conflicted heritage. American history brims with accounts of discrimination and injustice toward many minorities. The African-American experience since 1619 encompasses enslavement, terror, and violence. The wholesale slaughter of this country’s original inhabitants is a permanent stain on the nation. During World War II, the federal government interned Japanese Americans. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill apologizing and paying reparations to each survivor of those camps.

Yet, antisemitism has never figured prominently in this narrative of hate and prejudice. Antisemitism on American soil, by contrast, has been erased from this history. Recalling the bombings sixty-four years ago of a Miami synagogue and a Nashville Jewish center compels us to reckon with antisemitism’s deep roots in this nation’s past.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.