Expelled from Spain: July 31, 1492

“Recalling the pivotal events of 1492 in Spain compels us to recognize the complexity of patterns of hate and the urgency of addressing them.”

Just a few weeks ago, I stood in awe in the Alhambra palace in Granada. My Rutgers students and I were on a two-week trip to Spain to see the places we had studied all semester in an Honors Seminar—relics of centuries of coexistence between Muslims, Christians, and Jews. In that moment, the Alhambra’s dazzling architecture, graceful water fountains, and rose-filled courtyards stole our breath.

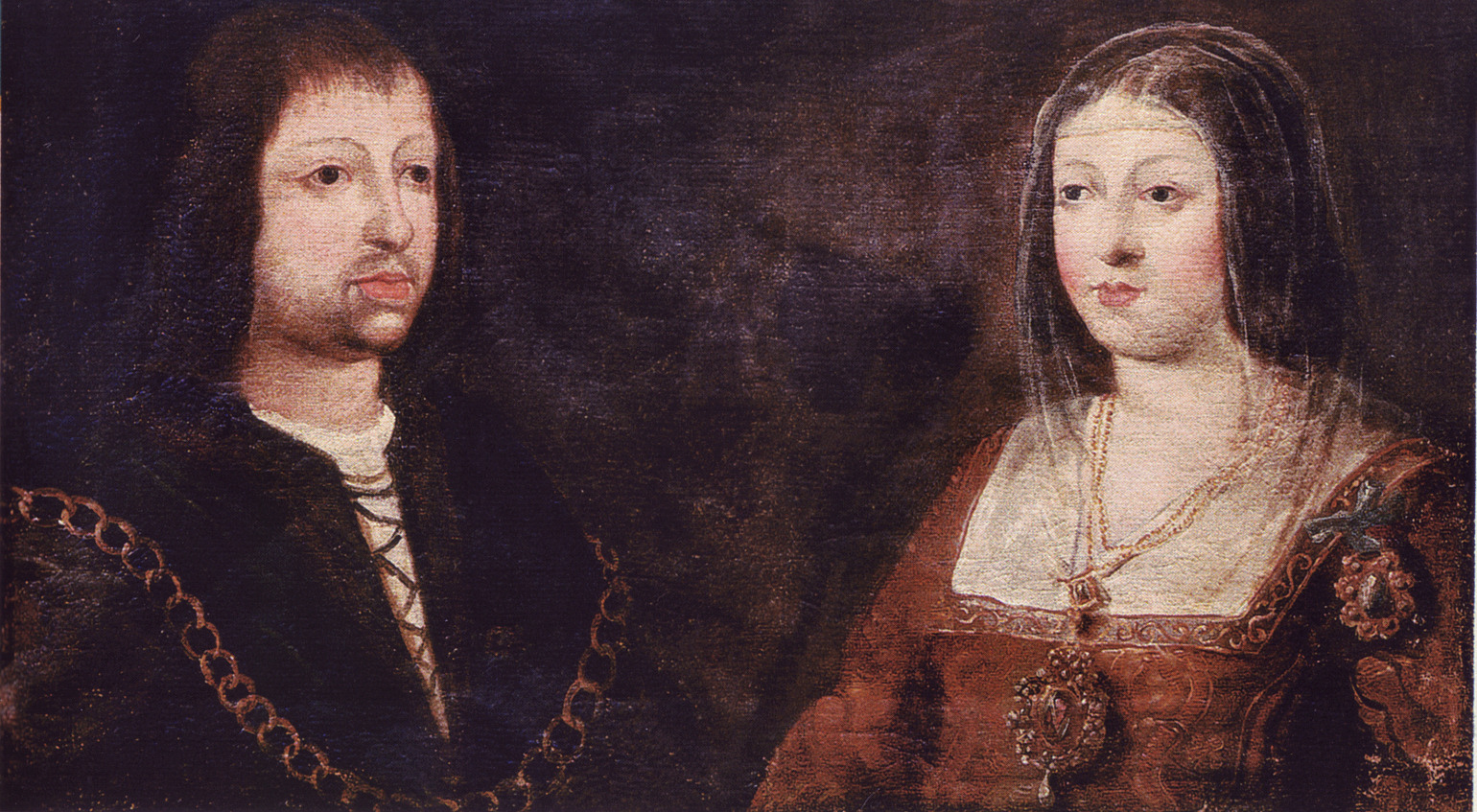

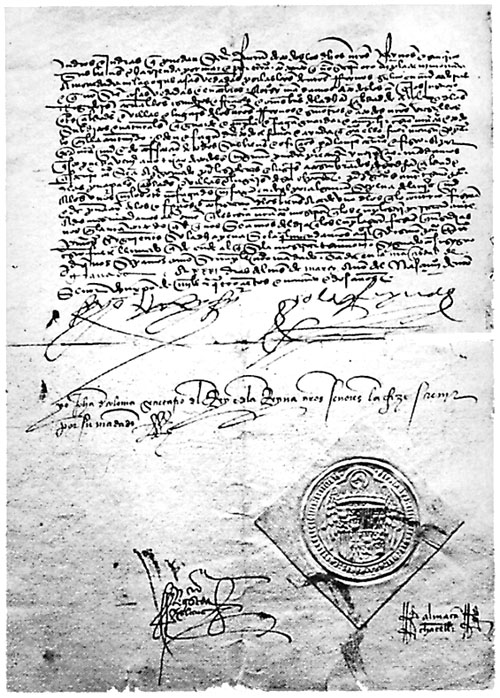

Yet, history weighed on us, too. We knew that this magnificent Nasrid fortress was bitterly surrendered to the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, on January 2, 1492, and that, thereafter, Muslims were forcibly converted to Christianity. We knew also that, on March 31, 1492, in the Alhambra’s resplendent Hall of the Ambassadors, Ferdinand and Isabella signed an edict, the Alhambra Decree, expelling the Jews from Spain. This document gave Spanish Jews four months—until July 31—to choose between abandoning their religion or leaving the land where their families had lived for over a thousand years.

What can we learn from these two medieval Spains—on the one hand, a land of religious pluralism, on the other, the epitome of religious intolerance? Recalling the pivotal events of 1492 in Spain compels us to recognize the complexity of patterns of hate and the urgency of addressing them. It reminds us that mass violence does not emerge out of the blue. Instead, it is propelled by a multiplicity of factors, including deep histories of prejudice and bigotry. It also reminds us that societal animosities seldom target only one group. In late medieval Spain, Jews and Muslims both endured forced conversion and exile. In fact, the edict of 1492 later served as a model for regional charters expelling converted Muslims.

“My students and I contended with these troubling truths during the months leading up to our trip, as we considered continuities, parallels, and differences between the past and the present.”

Medieval Spain is sometimes remembered as an interfaith utopia, a land where Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived together in peace. Under Muslim rule and, initially, under Christian rule, Muslims, Christians, and Jews experienced periods of economic prosperity and cultural flourishing. Members of all three communities collaborated intellectually, artistically, politically, and financially, and all three cultures shaped one another. Spectacular architecture—including Granada’s Alhambra—and literary, legal, and scientific masterpieces in Arabic, Hebrew, Latin, and Spanish are among the fruits of these dynamics that survive to this day.

But the coexistence of Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Spain was, in fact, never free of tensions.

Long before July 31, 1492, Spain was the site of massive religious violence—of massacres, forced conversions, inquisitorial torture, and expulsions. In fact, Christians forcibly converted Jews to Christianity as early as the fifth century. In 1391, thousands of Jews were baptized at sword’s point. These “Conversos” were suspected of continuing to practice Judaism in secret. To police Converso beliefs and practices, Ferdinand and Isabella established the notorious Spanish Inquisition in 1478.

In the meantime, the Doctrine of Purity of Blood was established which stated that that Jewish and Muslim “blood” was tainted, inferior, and ineradicable. This discriminatory policy undergirded the legal marginalization of descendants of Muslims and Jews, regardless of whether these individuals were baptized.

Thus, the mass expulsions of late medieval Spain drew on centuries of hate, even as they marked a turning point.

In 1492, and during the years that followed, tens of thousands of Jews fled Spain (estimates range from 40,000 to over 150,000). Describing the Jewish exiles of 1492, one eyewitness wrote:

“[In Portugal,] the king acted [even] worse toward [the Spanish Jews] than the king of Spain… He made slaves of [them] and banished seven hundred [Jewish] children to a remote island… [In North Africa,] many died in the fields from hunger, thirst, and lack of everything… [On the vessels that carried them to other countries,] the crews acted maliciously and robbed them… [In Naples,] some died by famine, others sold their children to sustain their lives. A plague broke out and many died, so that the living wearied of burying the dead.”

“July 31, 1492 notably coincided with the ninth day of the Jewish month of Av. A day of communal mourning, the Ninth of Av commemorates a roster of tragedies in Jewish history including the destruction of the first and second temples in ancient Jerusalem. Thus, the sixteenth-century chronicler Joseph Ha-Kohen called for his account of the Spanish Expulsion to be read aloud every year on the Ninth of Av.”

The expulsion of 1492 went down in Jewish history on a par with biblical calamities. “Jews’ fear in 1492 was unequaled,” wrote the Jewish courtier Isaac Abravanel, “since the exile of Judah from its land.”

Thousands of Jews who stayed in Spain converted to Christianity. Over the next decades and beyond, many Conversos left Iberia, heading not only to North Africa, Italy, and the eastern Mediterranean but also to Amsterdam and the Americas, sometimes returning to the open practice of Judaism. Meanwhile, the Spanish Inquisition (and its sister institution, the Portuguese Inquisition) expanded, establishing tribunals in Spanish and Portuguese colonies. By 1530, the Spanish Inquisition had sent some 2,000 Conversos to the stake. It also prosecuted Muslim converts, Protestants, and others accused of religious deviance.

The legacies of these developments defy enumeration and continue to make headlines. In 2015, in an ostensible effort at reparations, the Spanish Parliament voted to grant citizenship to anyone who could show that their ancestors included Jews who had been expelled from Spain. According to Spain’s Ministry of Justice, 132,226 people had applied for this program as of October 2019. At the same time however, my students are always particularly shocked to learn that residents of the Spanish town of La Guardia continue to celebrate the annual feast day of a fictitious local boy—the “Holy Child of La Guardia”—whom the Inquisition falsely and fatefully accused Jews and Conversos of murdering in 1491.

Exploring the Alhambra this Spring, my students and I delighted in the sights and sounds, and we were spurred to deeper reflection. We had spent the semester learning about Spain. Now in Spain, our thoughts turned to our own lives and the ways knowledge of history empowers us to recognize, and strive to dismantle, patterns of hate, wherever we find ourselves.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.