Coming to America

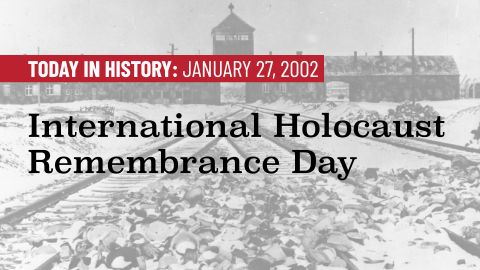

Editor’s Note: The new PBS documentary series, The US and the Holocaust examines America’s response to one of the greatest humanitarian crises of the twentieth century. Journalist Daniella Greenbaum Davis is not yet 30 years old, but the questions raised in the film are personal to her. For Today in History, she shares her perspective as a third-generation survivor.

“Raised on my family’s history, it wasn’t until college that I began to understand that my conception of America’s role in Jewish salvation was overly simplistic.”

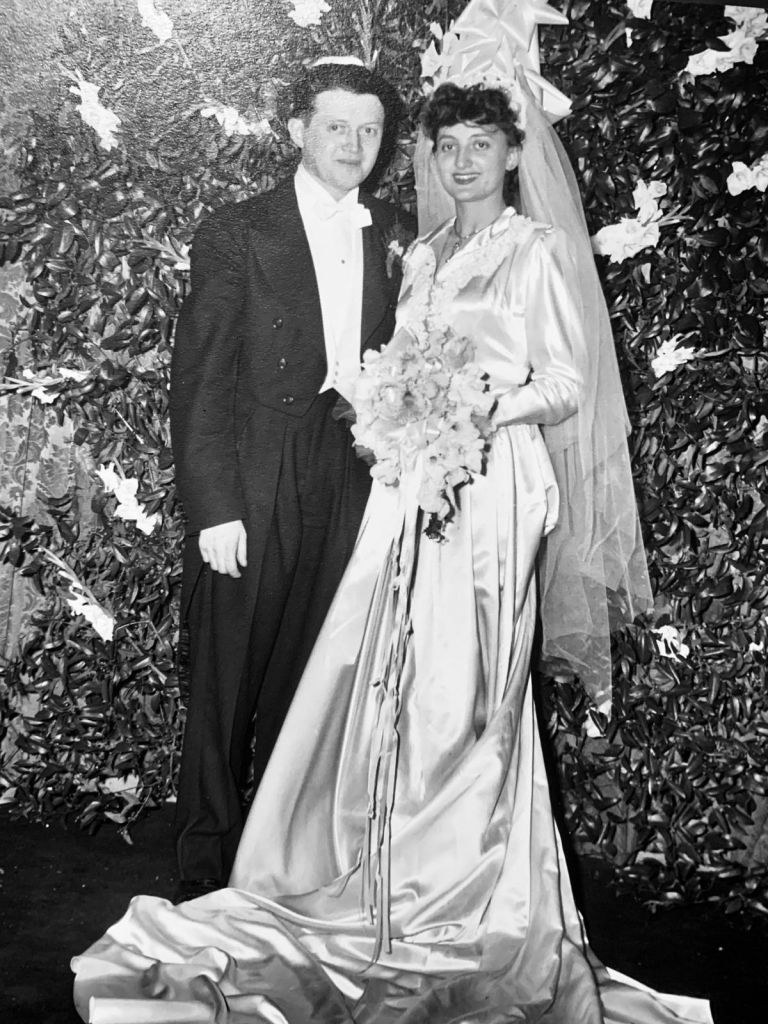

Growing up as the grandchild of Holocaust survivors and refugees in 21st-century New York, my conception of America’s role during World War II was simplistic and binary. For my family, it was totally black and white: good versus evil, genocide versus salvation. America was the heroic harbor which opened its arms to hungry, huddled masses and those masses included many members of my extended family. Both my maternal grandparents, Willy Apfel and Jenny Last Apfel sought and found refuge in this country from the storm clouds engulfing Austria and Germany in the 1930s and 40s.

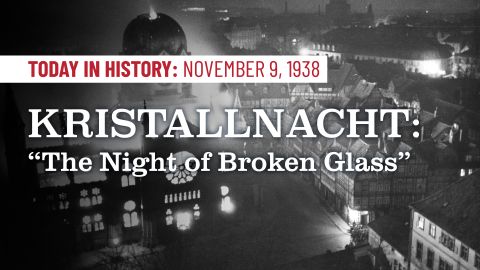

Upon arriving at immigration in the New World in 1937, my great-grandmother Sarah mumbled when asked why her documents bore two names — “Zelma,” and “Sarah.” Out poured a tragically common story of how, as a child in the early 1900s, well before the Nuremberg laws or Kristallnacht, her classmates bullied her for being Jewish. Instead of punishing the offenders, her teacher recommended that she Germanize her name, and thus, Zelma was born. The immigration officer smiled and told Sarah that her name was beautiful, that it was Roosevelt’s mother’s name, and that in America, she could be called by whatever name she chose. This welcoming, tolerant embrace was my family’s first, and oft-recounted experience with America.

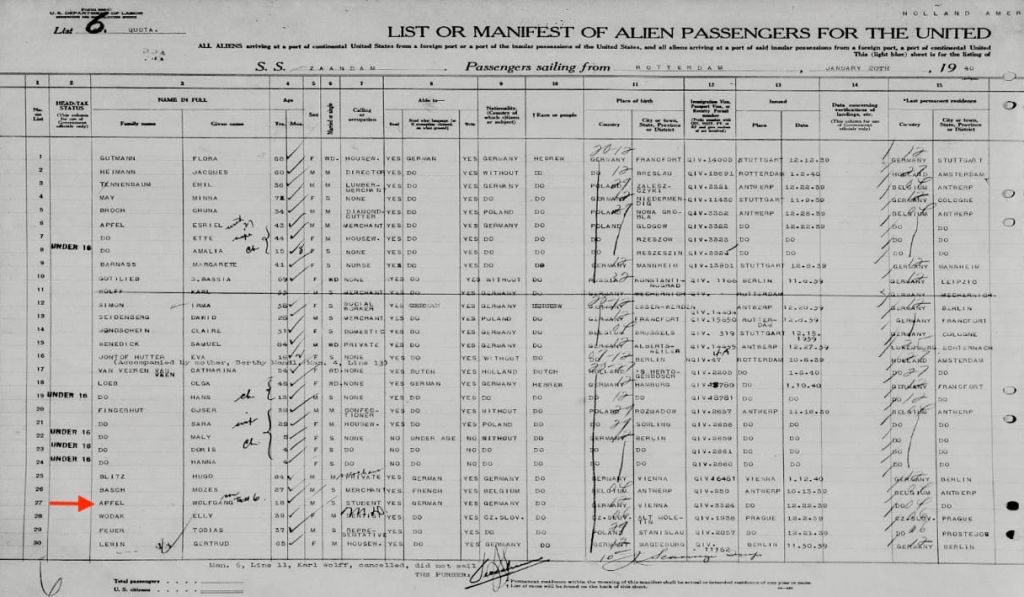

1940 Ship Manifest. Willy Apfel, fourth from bottom.

My grandparents had vastly different experiences growing up in pre-war Europe. My Viennese grandfather, Willy, (“Villy”), had an idyllic childhood. His memories of Austria were fond, until all of a sudden, weeks before the Anschluss, life turned on a dime. But for Jenny, my Berliner grandmother, childhood was an endless procession of increasing restrictions and embarrassments – signs comparing Jews to dogs, banning her from restaurants, parks, zoos, and all kinds of activities that an 11-year-old might have enjoyed in a freer land. Her father Max, was beaten to within an inch of his life for refusing to raise his hand for the Sieg Heil. The Apfels and Lasts left Vienna and Berlin relatively early on, but both would linger in Europe before ultimately securing the right to immigrate to the states. In a moment of utter desperation in Switzerland, Max Last, standing tall at over 6 feet, leaned over a much-shorter American immigration official, picking him up by just his collar. Max wouldn’t let go without the promise of visas for the family. The Apfels made their way to this country through a combination of luck, charm, and help from strangers. Each Jew who immigrated represents a triumph. Each has a story. Though many were let in, many more were never allowed to step foot on our soil.

My grandparents were the lucky ones. As news trickled in, neither harbored any illusions of what happened to the friends and relatives they left behind. After the war, the survivors they lived amongst were daily reminders of how different their lives could have been.

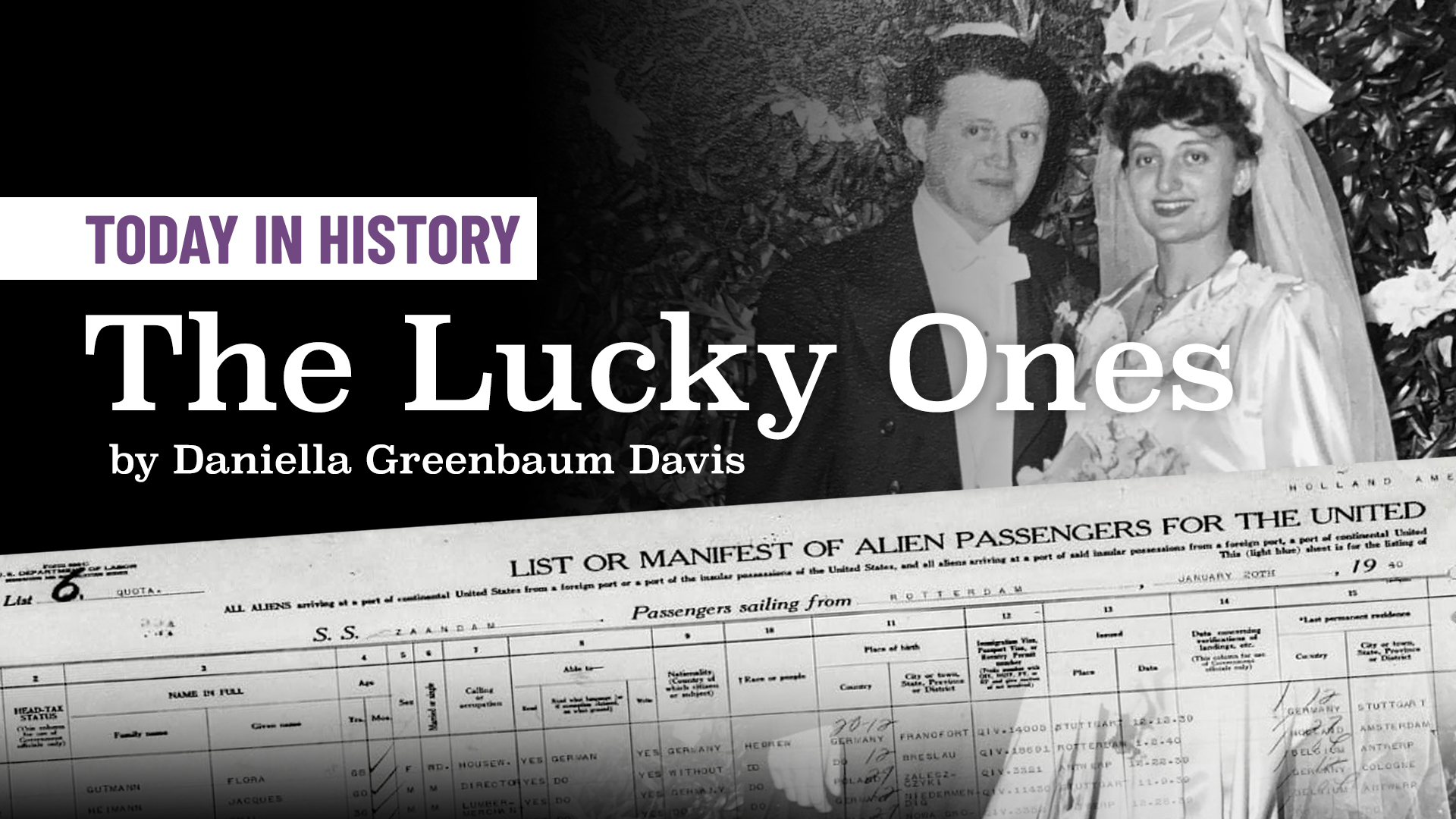

Willy and Jenny Apfel, 1950.

Raised on my family’s history, it wasn’t until college that I began to understand that my conception of America’s role in Jewish salvation was overly simplistic. This period, which sparked my grandparents’ life-long love of America, also brought some of America’s worst maltreatment of Jews. Knowing this historical dichotomy is essential for understanding the current paradigm in which many Jewish families are experiencing their most triumphant moments in America, while, in simultaneity, antisemitism is rising at meteoric rates.

“Each Jew who immigrated represents a triumph. Each has a story. Though many were let in, many more were never allowed to step foot on our soil. My grandparents were the lucky ones.”

Antisemitism has always been a fluid virus — it waxes and wanes, it mutates and grows; it exists here like it exists everywhere there are Jews. Recognizing the historic low points of American Jewish history, and confronting the diverse manifestations of modern American antisemitism are both crucial for ensuring this country remains a land of liberty and opportunity for Jews — and for everyone.

One of the crucial differences between European and American antisemitism is its roots, or lack thereof, in the ethos of the continent and the nation, respectively. America, unlike most European countries, does not have a history of antisemitism baked into its national culture.

In his 1790 letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, George Washington promised them “uncommon prosperity and security” in their new home. On May 14th, 1948, Harry Truman became the first world leader to recognize Israel, merely 11 minutes after its official establishment. And in the 1980s Ronald Reagan successfully lobbied the Soviet Union to begin liberating its tortured Jewish population.

Still, American history is not devoid of antisemitic moments. And many of the themes present in modern-day American antisemitism find their roots in the hatred of the past.

“Knowing this historical dichotomy is essential for understanding the current paradigm in which many Jewish families are experiencing their most triumphant moments in America, while, in simultaneity, antisemitism is rising at meteoric rates.”

American antisemitism has existed at all levels—among regular citizens and at the highest levels of government. In our moment of greatest need, during the war years, America shut its doors to millions of Jews who were not as lucky as my grandparents.

FDR’s State Department was at best apathetic and at worst antisemitic. The government had tight limits on immigration, and even sent refugees back to Europe, as they did with the 937 passengers of the St. Louis, many of whom the Nazis soon after killed. Roosevelt knew the grim fate awaiting these passengers. Nonetheless, his administration defended these decisions on the basis of “national security.” The implication – that Jews were spies — is the same kind of “dual loyalty” accusation that underpins many forms of modern antisemitism. Ironically, Jews fleeing Germany were too German to be trusted by the Americans, but not German enough to be spared by Hitler.

Jewish refugees in Cuba on SS St. Louis, 1939. Public Domain.

The Roosevelt Administration also refused to bomb the concentration camps or the tracks to Auschwitz, despite knowing what was happening inside and having the capability to do something about it. Although there are some who have argued that such a move would have detracted from the goal of defeating Germany —preposterous given the tiny scale of such a campaign—many see this unfortunate decision through the lens of antisemitism and apathy.

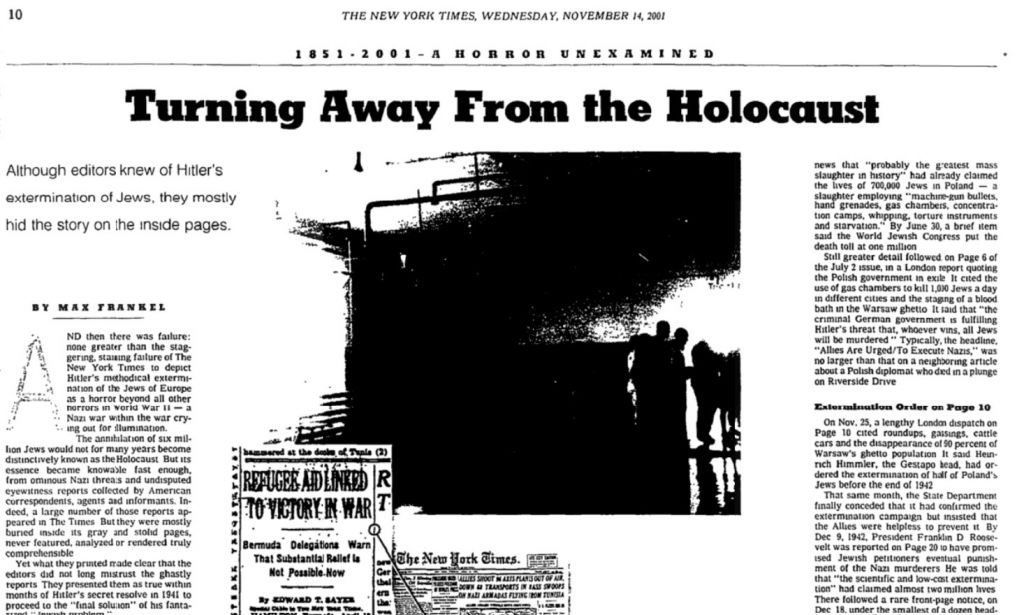

Jewish self-hatred is another form of antisemitism which is tragically on the rise, and almost never discussed. I argue that it was also responsible for a despicable campaign in which in-power elites tried, largely successfully, to close America’s eyes to the horrors in Europe during the Holocaust. Arthur Sulzberger, the Jewish publisher of the New York Times, and ancestor of its current publisher influenced the paper’s “reluctance to highlight the systematic slaughter of Jews” and “believed strongly and publicly that Judaism was a religion —not a race or nationality.” Because criticism of the paper of record has become so politicized, I took these quotes from the New York Times, a retrospective article from twenty years ago which refers to the paper’s coverage during this period as a “staining failure.” As with other forms of racism, antisemitism sometimes leads Jews to internalize the hatred against them and take action to prove their independence from the group. The article goes on to note that Sulzberger and his editorial page “refused to dwell on the Jews’ singular victimization,” and “was cool to all measures that might have singled them out for rescue or even special attention.”

The New York Times, November 14, 2001.

This determination to refuse to see Jews as victims is sadly relevant today when our status as a minority is constantly called into question and celebrities and public figures constantly portray us as white, privileged, and all-powerful.

But despite both the historic and modern examples of antisemitism in America, I can’t forget that this country gave my family refuge when it needed it most. And that despite its failings — in the past and in the present — this nation has religious and national tolerance baked into its DNA. Looking back at the war period dispassionately, and with the benefit of hindsight, we must acknowledge that America could and should have done more, and done it earlier. But we also can’t forget the countless Jewish lives that were saved because this country ultimately decided to open its doors.

Daniella Greenbaum Davis with her grandmother, Jenny Apfel, and her husband, Bobby Davis | 2018.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.