Ben Ferencz: Never Give Up

Across his nearly 80 years as a lawyer, Benjamin Ferencz has tried only one case. In it, he called only one witness, and he needed little more than one day to present his evidence. It was more than enough to send some of history’s most grotesque mass murderers to prison and even to the gallows. “If these men be immune,” he told the court, “then law has lost its meaning, and man must live in fear.”

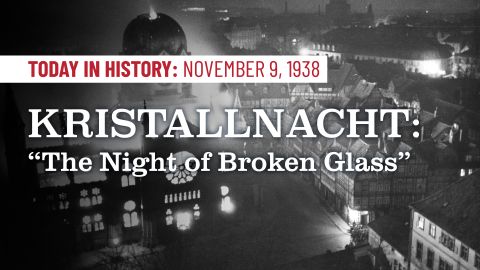

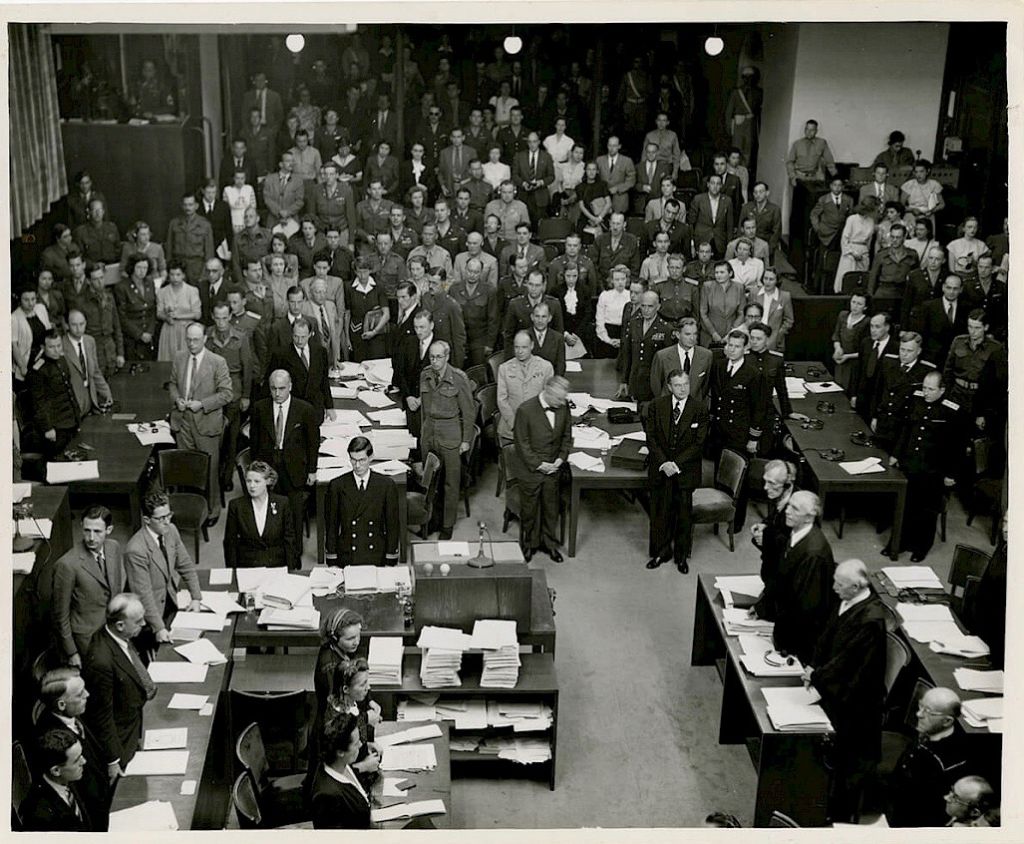

That was in the autumn of 1947. The courtroom was in Nuremberg, the German city where postwar judgment fell on the masterminds and willing cogs of the Nazis’ industrialized slaughter of millions of Jews, Roma, gays and others. A year earlier, leading Nazi figures had been put in the dock and sentenced to death, among them Hermann Göring, Martin Bormann and Julius Streicher.

Twelve other trials soon followed, of lesser-known men who were nonetheless integral to the Nazi killing machine. Mr. Ferencz’s trial was No. 9. He was then a 27-year-old from New York. Now he is 102, the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor.

As a soldier, he had borne witness to the evil of Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Flossenburg and other concentration camps. His task in 1947 was to prosecute 22 officers of the Einsatzgruppen, the politely named “deployment groups.” They were, in fact, paramilitary death squads responsible for killing at least 2 million people, including 1.3 million of the 6 million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. Mr. Ferencz did his job well. All 22 were found guilty, with 14 sentenced to death, though ultimately only 4 were executed.

“Vengeance is not our goal,” he told the presiding American judges. “Nor do we seek merely a just retribution.” Rather, he said, “the case we present is a plea of humanity to law.”

Benjamin Berell Ferencz (pronounced Fer-RENZ) would make that plea his life’s work, notably as a principal proponent of a juridical system to deal with acts of brutality that shock human conscience. His advocacy helped lead in 2002 to the establishment of the International Criminal Court, which the United States, to his dismay, has refused to join. In recognition of his efforts, he was invited to the Hague in 2012 to deliver closing remarks in the court’s first case: the successful prosecution of a Congolese warlord, Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, sentenced to 14 years in prison.

“The illegal use of armed force, which is the soil from which all human rights violations grow,” Mr. Ferencz said then, “must be condemned as a crime against humanity.”

He lives now in Florida, as committed as ever to his long-standing motto: “Law. Not war.” His dedication shapes this installment of Today in History, a series focused on past events with lasting resonance. For sure, antisemitism endures. In this country, its virulence is evident in increased attacks on synagogues and cemeteries, in the embrace of time-worn antisemitic tropes by celebrities like Kanye West and Kyrie Irving, in the hate-filled chants of 2017 marchers in Charlottesville, Va.

Across the decades, Mr. Ferencz has received various honors. In May, the House of Representatives voted to award him the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest legislative expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements. Senate action is pending.

Born in 1920 in what is now Romania, he was 10 months old when his family left for New York. He graduated from City College of New York in 1940 and from Harvard Law School in 1943. Barely 5 feet tall, he then was a soldier in Patton’s Third Army as it crossed the Rhine and fought the Battle of the Bulge. When the American Army reached concentration camps, he observed grim scenes, like that of prisoners beating up a German guard and burning him alive.

“Could I have probably stopped it? No,” he told The Washington Post in 2016. “Did I try? No. Should I have tried? No. You try being there.”

In 1946, returned to New York and newly married, he was unexpectedly summoned back to military duty – and the pursuit of justice – by Telford Taylor, lead counsel at Nuremburg in the prosecution of Nazi war criminals.

For the Einsatzgruppen trial, Mr. Ferencz stripped his presentation to a bare minimum: no witnesses other than a man who attested to the authenticity of the Nazis’ accounts of their own barbarism. Meticulous record keepers, they were hanged by their own words – entries that told of 10,000 Jews “liquidated” in Minsk, of 34,000 murdered in Kyiv, of entire towns “cleansed of all Jews.”

The young lawyer needed but two days to make his case. The accused took much longer trying to justify their actions. Some boiled it down, absurdly, to an argument that Germany had acted in self-defense against the threats of communism and Jewish Bolsheviks. The prosecution prevailed.

So did civilization, many would say, though years later Mr. Ferencz took a somewhat different tack. “These men would never have been murderers had it not been for the war,” he told the CBS show “60 Minutes” in 2017 and added, “War makes murderers out of otherwise decent people. All wars, and all decent people.”

After Nuremberg, Mr. Ferencz remained in West Germany until 1956, handling restitution claims brought by the Nazis’ victims and negotiating a reparations agreement between the West German government and Israel. After returning to New York, he joined a law firm led by Telford Taylor and taught international law at Pace University.

But his passion lay in the creation of the international court to bring mass murderers to justice. He urged, in vain, that the United States join it. He argued that Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein should have been brought to justice, not killed. He suggested that President George W. Bush might well have been brought up on war crimes charges stemming from the invasion of Iraq.

He kept at it even as he entered his second century.

“Never give up,” he said. “Keep going.”

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

Ben Ferencz Nuremberg video courtesy of the Robert H. Jackson Center.

For more about the Nuremberg trials, visit Exploring Hate’s Legacy Archive Project.