Against Mind and Heart

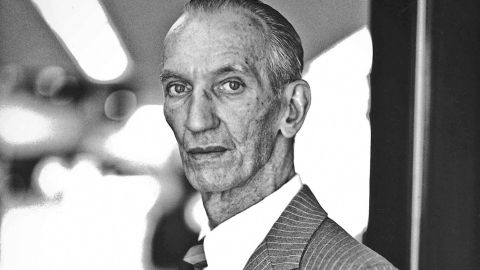

One day in 1943, the truth collided with a very human failing: our inability to believe those facts which are too awful to bear. The collision occurred in Washington, D.C. The two players were Felix Frankfurter, who four years earlier had become only the third Jew ever appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and Jan Karski, a Pole of aristocratic bearing who brought word of the horrors then underway in his home country.

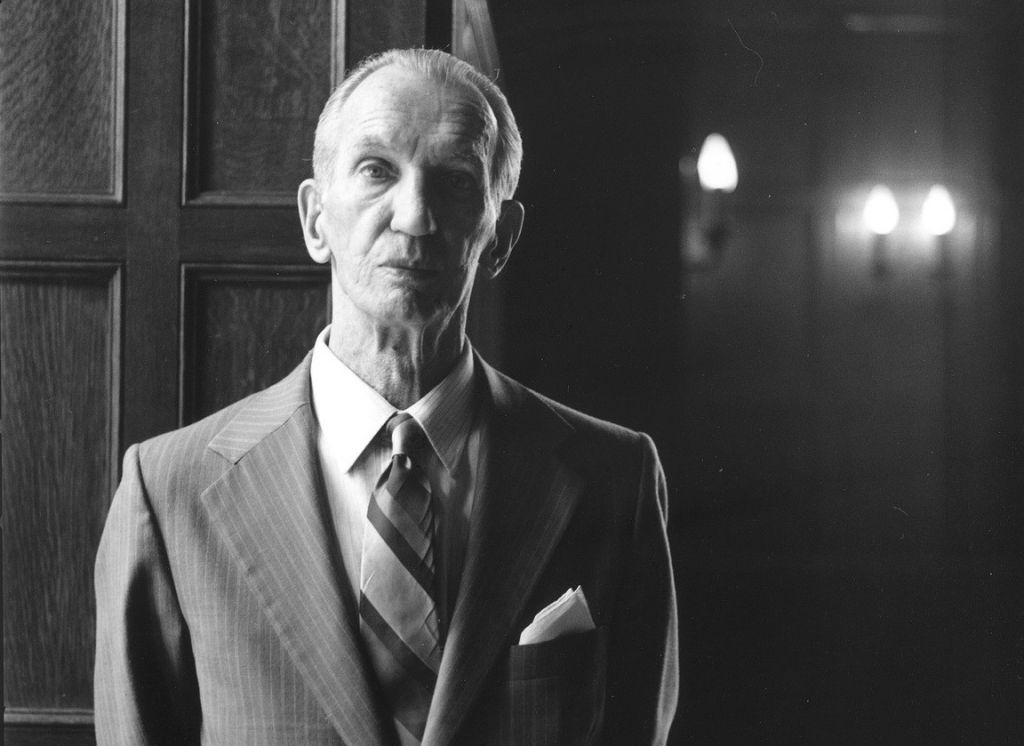

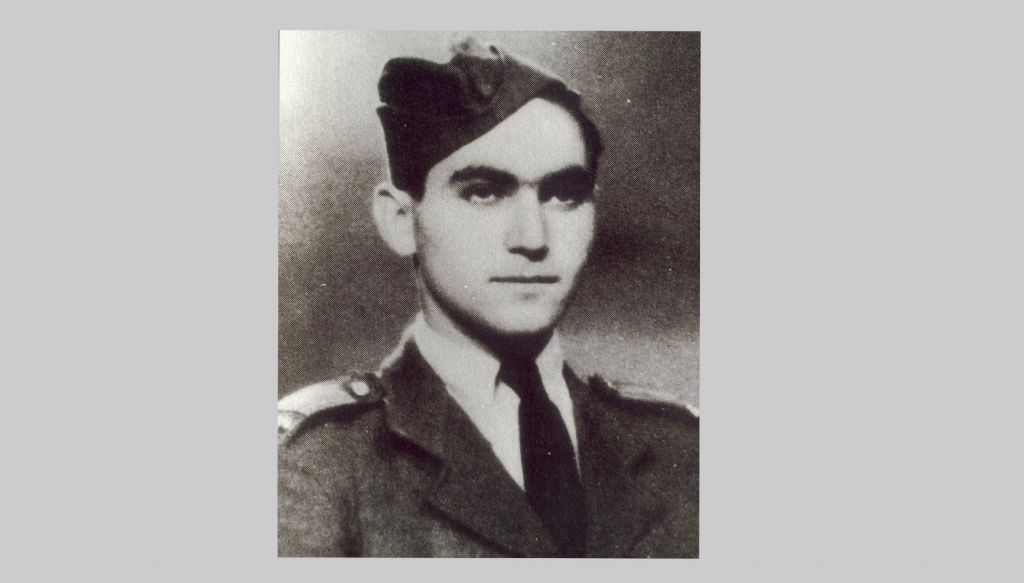

Karski, whose story is told in Remember This starring David Strathairn and airing nationally on PBS’s Great Performances on March 13, would later refer to himself rather modestly as a “courier.” The message he was carrying was his own eyewitness testimony: he had seen what the Nazi occupiers of Poland were doing to the Jews whose masters they had become. Karski had gone undercover, twice, inside the Warsaw ghetto, and he had seen the Izbica transit camp. He did not know the whole story, but he knew enough to describe mass shootings as well as the loading of Jews onto freight cars which were then sent to “special camps at Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor,” supposedly for the purpose of resettlement. “Once there, the so-called ‘settlers’ are mass murdered,” he wrote. Now he was in Washington to brief one of America’s most eminent judges.

Frankfurter did not react as Karski expected. After listening to the Polish courier for 20 minutes, the judge said, “I do not believe you.” The diplomat who had brought Karski to Washington felt compelled to defend the credibility of his countryman: “He is not lying!” he insisted.

“I did not say that he is lying,” the judge replied. “I said that I don’t believe him. These are different things. My mind and my heart are made in such a way that I cannot accept it. No. No. No.”

The judge was admitting to a human quality—defect might be a more honest word—that is rarely discussed: we struggle to absorb information from which we recoil, that either appalls or terrifies us or both. That failing would be confirmed even more dramatically the following year.

In April 1944, a Slovak Jewish prisoner, later to be known as Rudolf Vrba and then just 19 years old, would become one of the very first Jews to escape from Auschwitz. Together with his fellow Slovak Alfred Wetzler, the pair would accomplish one of the most remarkable feats of World War II. Not only did they pull off an extraordinary act of daring and ingenuity in getting out of the camp, they also fled through Nazi-occupied Poland, as Vrba would later put it, “without documents, without a compass, without a map, and without a weapon.” Moving only at night, they crossed mountains, rivers, forests, and marshland and, in one of several brushes with death, dodged German bullets, until they reached the border with their home country.

Once in Slovakia, they made contact with the country’s remnant Jewish community and, hiding in a basement in a provincial town, they poured out the details of what they had witnessed and survived in Auschwitz. They were aided by Vrba’s freakishly good memory: he had made a mental note of every transport of Jews he had seen arrive during the nearly two years he had been an Auschwitz prisoner. He could give the date, point of origin, and estimated numbers for each trainload of Jews that had pulled into the camp, trainloads that delivered children, women, and men to their deaths.

The result was a 32-page, single-spaced document that would then embark on an escape story of its own—passed hand-to-hand across borders, secretly smuggled by resistance activists and diplomats through occupied Europe until it reached the desks of Winston Churchill in London, Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, and Pope Pius XII in Rome. But what Vrba and Wetzler did not bargain for was a recurrence of the same reaction Frankfurter had shown to Karski: disbelief.

Sometimes that incredulity came laced with prejudice. Witness the British official who wrote of the Vrba-Wetzler report on August 26, 1944, “Although a usual Jewish exaggeration is to be taken into account, these statements are dreadful.” Or the response of the U.S. Army journal, Yank, which declined to use material from the report for a feature on Nazi war crimes, finding it “too Semitic,” asking instead for a “less Jewish account.”

“The judge was admitting to a human quality—defect might be a more honest word—that is rarely discussed: we struggle to absorb information from which we recoil, that either appalls or terrifies us or both.”

But often the disbelief was just that—disbelief—untainted by bigotry. When the report reached the people Vrba had most wanted to warn—the Jews of Hungary, then the last Jewish community not yet pulled into the Nazi inferno—Samu Stern, the president of the Jewish council in Budapest, suggested that the Vrba-Wetzler testimony might be the product of the fertile imagination of two rash young men. For multiple reasons, including some still fiercely contested to this day, the Hungarian Jewish leadership chose not to distribute the warning Vrba and Wetzler had done so much to deliver.

Nevertheless, some glimpsed it. One of them was a boy roughly the same age as Vrba, György Klein, who worked in the Budapest offices of the Jewish council. The instant he read the words Vrba and Wetzler had set down, the instant he became convinced that deportation meant death, he resolved to act. He passed on the warning to his uncle, but the older man was not grateful. Instead, he was furious with his nephew for passing on such obvious nonsense. When Klein visited other relatives and friends, a pattern emerged. Those who were young believed him and began to make plans to evade the deportations. But the middle-aged, those who, like his uncle, had dependents, careers, and property—those who had much to lose—refused to believe what they were hearing.

And finally there is Czesław Mordowicz who, just a few weeks after Vrba and Wetzler, also escaped from Auschwitz. In a bitter twist, Mordowicz was caught by the Gestapo and sent back to the death camp. Inside the cattle car, he told his fellow deportees what awaited them. He urged them to jump off the moving train, to get away while they still could. They didn’t simply disbelieve him. They began shouting, summoning their German captors, urging them to eject this troublemaker. They attacked Mordowicz and beat him so badly, he was all but incapacitated.

“My mind and my heart are made in such a way that I cannot accept it. No. No. No.”

Shortly after I’d completed the manuscript of The Escape Artist, my book about Rudolf Vrba, in February 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine. The papers were full of stories of Ukrainians phoning their relatives in Moscow, describing the nightly bombardment—and their Russian relatives’ refusal to believe them. Around the same time, Netflix aired the movie “Don’t Look Up,” satirizing our refusal to pay attention to the climate emergency.

Both were echoes of the story of Rudolf Vrba and, before him, Jan Karski, men who brought out from the abyss a desperate warning, only to run headlong into a very human weakness: our inability to absorb bleak news, especially when that news portends our imminent destruction.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.