Until You Are Remembered

There’s a vintage sign on the bookshelf in my office here at the University of Michigan, where I’m a professor. My students are often shocked and offended to see the words it bears, “No Dogs, Negroes, Mexicans.” This artifact is from 1942, a time when signs like this hung across much of the Southwest.

That they are no longer in use is partly due to a GI from South Texas who was killed fighting the Japanese in World War II. His name was Felix Longoria, and he was born 103 years ago today, April 16, 1920. While most people have never heard of him, he played a critical role in transforming nearly every aspect of American life. The irony is that Longoria wasn’t an activist when he influenced the nation. He wasn’t even alive.

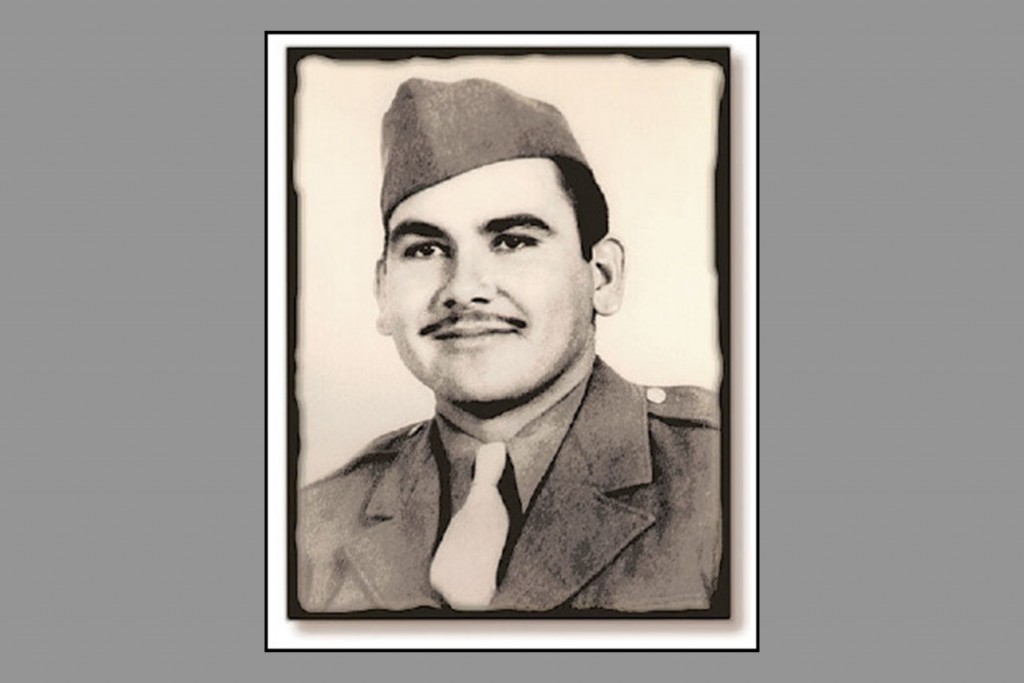

Longoria, like many Americans, volunteered to fight in World War II. He was sent to the Philippines and in 1944, at age 25, was killed in Luzon, where he posthumously earned a Purple Heart.

Four years later his remains were sent to his hometown of Three Rivers, Texas, for a proper burial. But the only funeral home in the county refused to let his wife, Beatriz, use the small funeral chapel because, as the owner told her and later a local reporter, “The whites wouldn’t like it.” Beatriz was distraught, but she shouldn’t have been surprised. The town had long been segregated, with a “Mexican” part and school on the other side of the railroad tracks from the town center. Even the cemetery had a section for “Mexicans,” and signs like the one in my office were not uncommon. Americans of Mexican descent generally kept their heads down and avoided confrontation. And for good reason: in proportion to their numbers, Mexican Americans in the West were lynched as often as African Americans in the South.

Change for Mexican Americans was slow in coming. Small in number, they were for the most part uneducated, disproportionally impoverished, almost always segregated, and often fearful and traumatized. With World War II things began to change. Half a million Latinos served, and many had distinguished themselves with acts of heroism. From Purple Hearts to Silver Stars to Congressional Medals of Honor, Mexican Americans were the most decorated of any ethnic group. They had earned the respect and admiration of their commanders, sharing the same hopes and fears, boredom and terror. After facing down Nazi and Japanese storm troopers, Mexican Americans were less willing to tolerate white violence and bigotry at home.

When Beatriz’s sister heard what happened at the funeral home, she contacted Hector P. Garcia, a medical doctor who ran a clinic in Corpus Christi. During the war Garcia had commanded mobile surgical units in North Africa and Europe, earning six Bronze Stars for combat heroism. Discharged with the rank of major, he founded the American GI Forum. Made up of recently discharged soldiers, it quickly became the nation’s largest Latino civil rights organization.

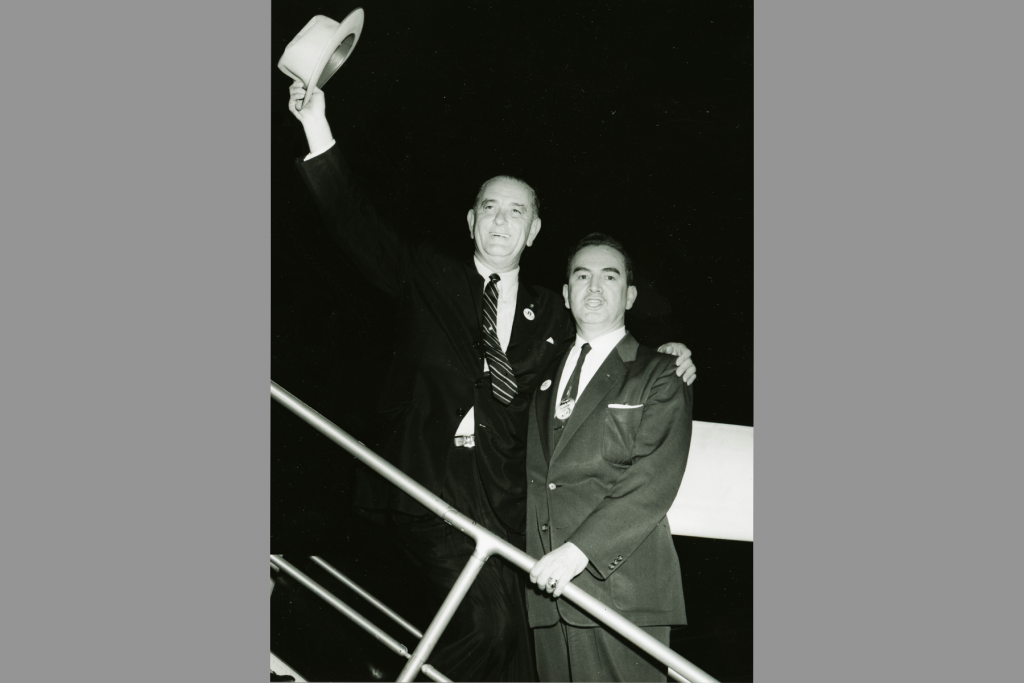

Garcia sent off a dozen telegrams demanding justice for Private Longoria. He wrote to President Truman, the Secretary of the Army, and the Governor of Texas. But the only person to respond was the junior senator from Texas, who had just been elected. His name was Lyndon B. Johnson, and he was livid. Having served during the war as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve, he felt this was an insult to all who had fought and died. He also felt an even deeper connection. He had grown up desperately poor in rural Texas and taken a teaching job after his freshmen year of college to pay for school. At the segregated “Mexican” school in Cotulla, Texas, about an hour west of Three Rivers, Johnson saw up close the discrimination, poverty, and waste of human potential and learned “the high price we pay for poverty and prejudice.”

Johnson worked with Garcia to have Longoria buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery just outside Washington, D.C., in February of 1949. They arranged for family members to attend and put them up in a fancy hotel. And they continued working together long after the Longoria Affair to advance the fortunes of Mexican Americans, securing them government jobs and greater access to the ballot box. But because Johnson’s political supporters and patrons were wealthy southern segregationists and outright racists, this work was done in secret.

It was not until Johnson became president in 1963 and began pushing forward civil rights legislation that his private alliance with Garcia became public. Stunning and outraging his supporters, Johnson ushered in the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. A year later, he signed the historic Voting Rights Act, which made it possible for Mexican Americans, African Americans, and other minorities to participate in the electoral process at last.

In his address to Congress and the nation, Johnson publicly revealed his personal motivation, saying:

“My first job . . . was as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas, in a small Mexican American school . . . My students were poor, and they often came to class without breakfast, hungry . . . Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child . . . It never even occurred to me in my fondest dreams that I might have the chance to help the sons and daughters of those students and to help people like them all over this country. But now I do have that chance. And I’ll let you in on a secret—I mean to use it.”

Sixteen years after the Longoria Affair, Johnson would go on to bring more Mexican Americans into the federal government than any president in history. The Voting Rights Act would lead to the election of Latinos to local school boards and city councils, and as mayors, legislators, senators, governors, and judges in unprecedented numbers across the country. For Dr. Hector P. Garcia, it was a triumph. For the nation, it revealed we could summon the courage, the compassion, the strength of character, the vision, and the grit to bridge the distance between what is and what ought to be.

And yet the Longoria Affair, like Latino history itself, is not widely known. One reason is the lack of highly educated Mexican Americans to do the research, write the books, and make the films that tell their history. While 42 percent of white people have a four-year college degree, only about 13 percent of Mexican Americans do. The figures are even more stark at the graduate level: only 1 percent of Mexican Americans have advanced degrees, compared with 14 percent of whites.

But perhaps the biggest reason is racism. Mexican Americans tend to be educated in underfunded schools and live separate lives from their white brothers and sisters. Rarely are their contributions to the American story integrated into the curriculum.

Maybe by acknowledging the hatreds of the past, we can find a new road forward, and events like the Longoria Affair will finally enter the chapel of our national memory.

Feliz Cumpleaños, Felix Longoria. Until you are remembered, we will not forget. You are a hero in ways you never knew and could never have imagined.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.