Salvation and Alliance

by Charles L. Chavis, Jr.

Editor’s note: The story of how Jewish refugee professors fleeing the Nazis were shunned by U.S. antisemitism but welcomed by America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) is a little-known yet important lesson in solidarity. The film “From Swastika to Jim Crow”—streaming here—documents the struggle and the embrace.

Exploring Hate talked with George Mason University’s Dr. Charles L. Chavis, Jr., historian of racial violence, civil rights activism, and Black-Jewish relations about how those historical insights continue to resonate today.

The interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Exploring Hate: Why did Jewish refugee professors end up teaching at HBCUs?

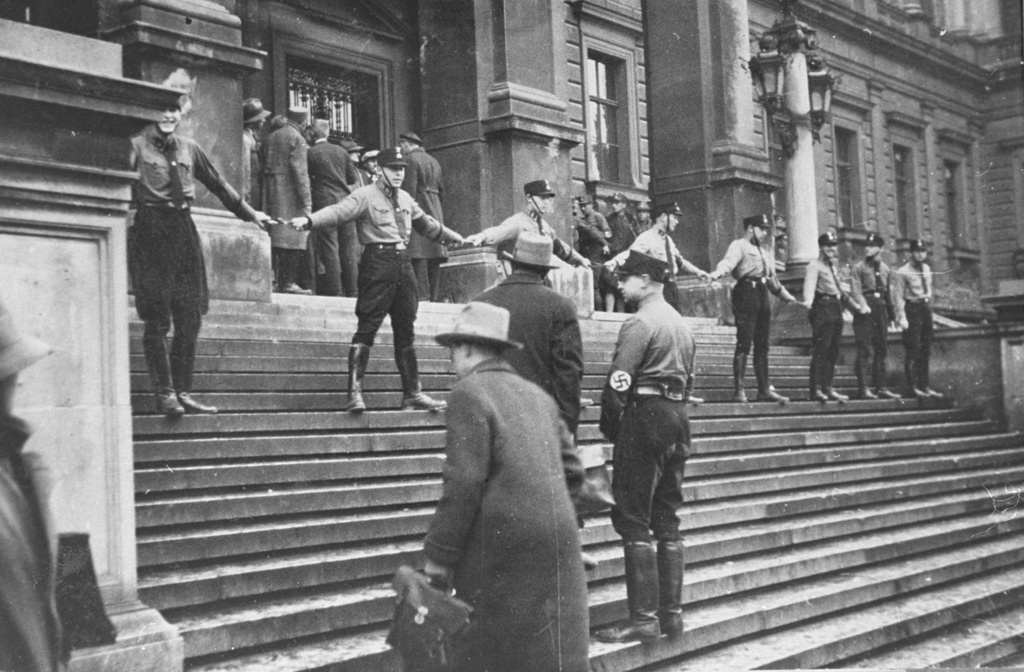

Charles Chavis: In many cases, HBCUs were the only organizations willing to sponsor Jewish refugees’ visa applications. Antisemitism was entrenched in historically white institutions from Harvard to the University of Maryland to Stanford, to name just a few, and many had previously implemented quotas on American Jewish faculty and students. These quotas became even stricter as a direct response to the influx of Jewish refugee professors. More often than not, American systems actively barred Jewish refugees, including Jewish scholars, from entering the United States. So HBCUs were among the only safe havens of higher education for Jewish refugee scholars.

EH: What made HBCUs open to hiring them?

CC: HBCUs—unlike historically white American universities—rarely had the privilege, or the depravity, to deny scholars of any race an opportunity to teach students. Nor did they wish for their students to be deprived of some of the best multiracial, interfaith scholars from the global community.

EH: How did Black students and Jewish professors see one another and react to one another?

CC: We have learned from oral histories and newspaper accounts that many Jewish refugee scholars had little exposure to Black people prior to their arrival at HBCUs. This isn’t to say that Black people did not exist in Germany. Afro-Germans were similarly targeted by the Nazi regime with various forms of persecution, including sterilization and violence during the 1930s.

Black students, particularly at Maryland HBCUs, were aware of local Jewish congregations and recognized their support of the Black liberation struggle. There was a deep-rooted Black-Jewish alliance in Maryland, which was exemplified by the anti-slavery and anti-lynching advocacy of Rabbis David Einhorn and Edward Israel. Shortly after Adolf Hitler rose to power in Nazi Germany, Rabbi Israel—together with the Black press, Black intellectuals, and Black institutions such as the NAACP—began prophetically warning both Black and white interracial and interfaith congregations of the horrors that Hitler was capable of.

It was commonplace, then, for a mutual warmth, rapport, and empathy to develop between Black students and their Jewish professors. As a student instructed by Ernst Manasse (featured in the documentary) at North Carolina University wrote in the school newspaper: “these teachers cared for us, they demonstrated a recognition of the barriers we had to confront and committed themselves to arming us with what we needed to survive it all.”

EH: How did Jewish professors respond to prejudice in the South having just fled from Nazi Germany?

CC: The ubiquity, severity, and seeming inescapability of anti-Blackness in America surprised and alarmed Jewish refugees. Even Jewish scholars with a background in history, global affairs, and similarly rigorous studies were taken aback.

“It was a great good luck of mine to find my first teaching job at a Black university where I felt I had so much in common with teachers and students.”

John Herz, Howard University, quoted in PBS documentary “From Swastika to Jim Crow”

EH: What role did your alma mater, Morgan State University (formerly College), in Baltimore, Md., play?

CC: Morgan State became an epicenter for Jewish refugees in the Upper South. This is largely thanks to its first Black president, Dr. Dwight Oliver Wendell Holmes. During his tenure, Dr. Holmes reversed the traditions of Jim Crowism, antisemitism, and white supremacy that white presidents at Morgan had historically respected.

Dr. Gerd Ehrlich was a Jewish refugee scholar who joined Morgan’s faculty in 1949. Professor Ehrlich’s journey to Morgan began in 1938, after he was expelled from high school following the Kristallnacht pogrom. He escaped from a forced labor camp near Berlin and used false papers to apply for an American visa. An expert in German language and political science at Morgan, Dr. Ehrlich was remembered fondly by his students as a supportive, empathetic mentor who truly cared for his students. And he was one of many so remembered.

Gerd Ehrlich, Berlin, between 1940 and 1943. Photo credit: Jewish Museum Berlin, inv. no. FOT 89/500/110/001.

EH: What inspired you to study Black-Jewish relations?

CC: It was during my time at Morgan State that I learned of the radical roots of Black-Jewish relations in the United States—focusing specifically on Black and Jewish leaders of the anti-lynching struggle during the 1930s and 1940s. This Black-Jewish coalition laid the foundation for future advocacy during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s and has more to teach us today as we seek to combat anti-Blackness and antisemitism.

EH: What do you find most significant about this chapter of Black-Jewish American history?

CC: The meaningful intersection between Black and Jewish histories forces us to sit with the fact that American institutions did not make every effort to aid Jewish refugees. This shatters the mythologies surrounding America and the Holocaust.

It also shows us that the friendship and camaraderie shared among Jewish refugee scholars and HBCU communities laid the foundation for a web of Black-Jewish alliances that climaxed during the Civil Rights Movement and that must be revived today. With the modern-day mass murders of Black and Jewish American citizens in their houses of worship (for example, in Charleston, S.C., and Pittsburgh, Pa., respectively), we are painfully reminded of how our struggles are linked in this country—and how urgently interfaith, interracial solidarity is needed once again.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Arlington National Cemetery, February 6, 1968. Photograph by John C. Goodwin.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.