Changing the Face of America

by Mae Ngai

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act on October 3, 1965, on a blustery day in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, he announced the end of discrimination in U.S. immigration policy. The new law would apply to individuals, not nations. It would do so by determining a prospective immigrant’s individual qualifications rather than their national origin or race. It was in line, Johnson said, with America’s democratic tradition, which “values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man.”

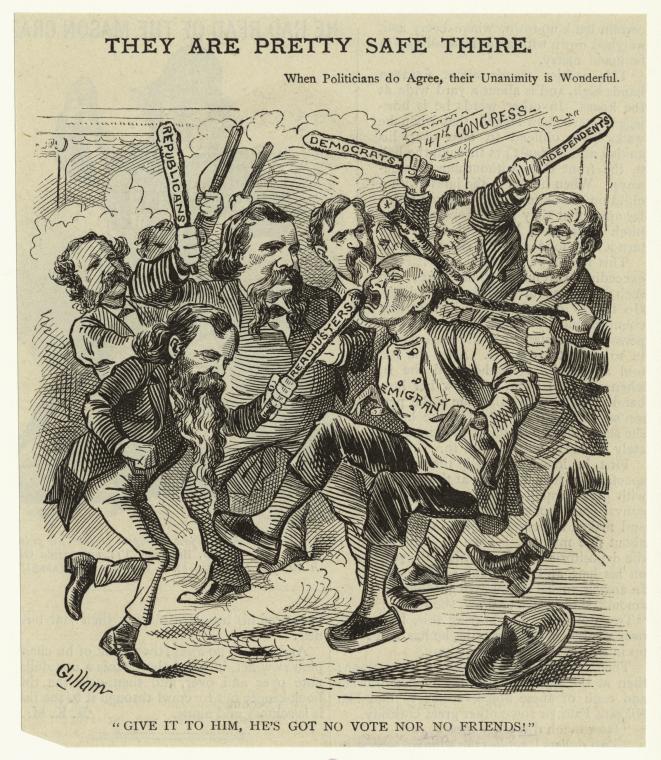

The law was a victory against the blatantly racist national-origin quotas, which since 1924 had imposed minuscule quotas on Southern and Eastern Europeans and excluded Asians altogether. President Johnson called the quotas a “deep and painful flaw in the fabric of American justice” and “a cruel and enduring wrong.”

And yet, notwithstanding the soaring rhetoric, the 1965 law, known as Hart-Celler for its congressional sponsors, would ultimately turn out to have a more ambiguous legacy. It would also provide the legal structure that allowed nativism to endure in the United States, to the point where anti-immigrant sentiment has become the bedfellow of anti-Black racism in our current moment.

The growth of non-white immigrant communities in the United States since 1965 took place not because of Hart-Celler but in spite of it. When lawmakers repealed the national-origin quotas, they sought to benefit Europeans. They did not welcome or foresee any significant increase in immigration from the Global South. In fact, they deliberately structured the law to discourage immigration from Mexico, the Caribbean, and Asia.

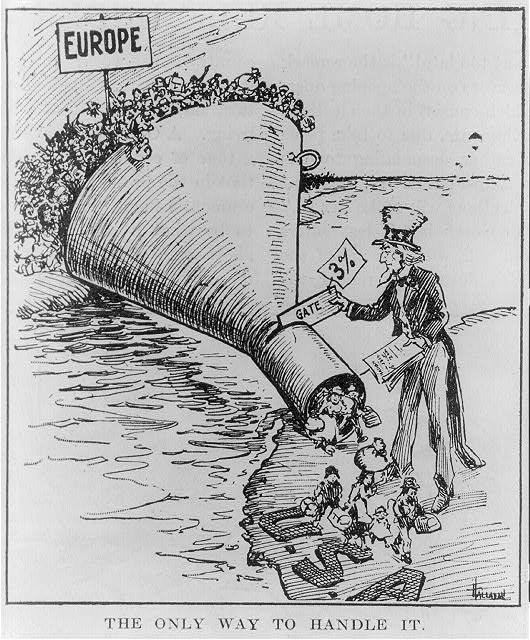

They did this in two ways. First, they kept the overall ceiling on immigration low, capping the number of immigrants from any one country at a maximum of 20,000 a year. A Congressional select commission called imposing the country-limit on Mexico, where there had been none before, a “retrogressive step.” Congress did it anyway, in the name of “fairness” and out of concern that population growth in Latin America would lead, without immigration restrictions, to a “sudden flood” from the region and a potentially “ugly” situation, according to the New York Times.

The growth of non-white immigrant communities in the United States since 1965 took place not because of Hart-Celler but in spite of it.

Second, Congress gave 80 percent of new visas to immigrants with family members in the United States, believing that meant Western and Northern European families would remain dominant. Some cynically hoped that the family preferences would achieve the same results as the national-origin quotas, that is, keep the nation white.

What actually happened? A surveillance state on the southern U.S. border and a persistent suspicion of Asian immigrants ensued.

The “fairness” principle did not limit migration from Mexico and Latin America but instead promoted unauthorized migration and created a regime of surveillance, apprehension, and deportation. Ongoing demands for labor in agriculture and service industries continued to generate high levels of undocumented immigration from Mexico. In 1976 (the year the 20,000 annual limit on Mexico went into effect), immigration officials expelled over seven times as many Mexicans from the U.S. as the total from all other countries combined.

Since Hart-Celler the idea that Mexicans are “illegal” has become central to their racialization as criminals and undesirable immigrants. The stigma passes generationally to their U.S.-born children, who are citizens, and now attaches to Central Americans, the main group recently coming across the U.S.-Mexico border. Although they are asylum seekers fleeing civil wars and gang violence, they are treated as unauthorized border crossers.

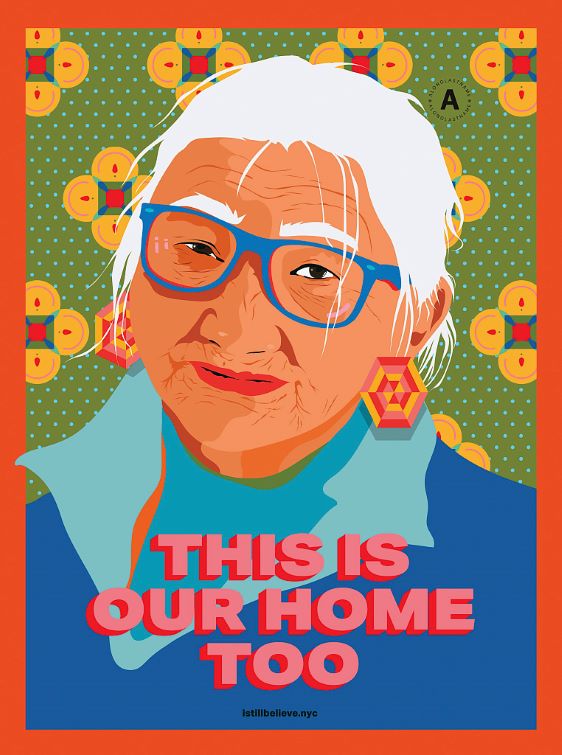

What about Asian immigration? The first wave of immigrants from Asia after 1965 came under the occupational preferences—nurses, doctors, engineers, and lab scientists. These professionals were in demand for growing industries in health care, telecommunications, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals. Once settled in the United States, they could become citizens in five years and then use the family unification preferences to bring their family members. This pattern explains the entry and growth of the educated classes that fed the so-called model minority myth. The Asian American population practically doubled every ten years, reaching about 24 million in 2020. Although they are still less than 6 percent of the total U.S. population, many Americans believe there are “too many” Asians in the country, suggesting enduring fears of the “yellow peril.”

Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, “This Is Our Home Too,” 2021. Copyright © Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya. Poster for New York City Commission on Human Rights to combat anti-Asian discrimination, harassment, and bias as a result of COVID-19.

Because Hart-Celler did not envision increases in immigration from Asia and Latin America it has been called a prime example of the law of unintended consequences. That’s true, but it’s also not that simple. Hart-Celler was a product of the 1960s civil rights era, which defined “fairness” in terms of formal equality but without addressing real inequalities.

When President Johnson stood beneath the Statue of Liberty and decried the national-origin quota act to be racist and un-American, he had Italians and Jews in mind, not Mexicans and Chinese. Hart-Celler repudiated discrimination against European ethnic groups and promoted their assimilation as white Americans. But there was no reckoning with the historical exclusions that racialized Latino and Asian people in the United States. Hart-Celler’s structure—which remains in our immigration law today—embodies the idea that non-Europeans are not welcome, not desirable, and not worthy of full inclusion in the nation.

Today in History features stories that probe the past and investigate the present to better understand the roots and rise of hate. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author.

Top photograph: Trans-Pacific passengers at the U.S. Quarantine Station, Angel Island, Cal., 1924. Courtesy of NARA, Department of the Treasury, Public Health Service.