Staten Island Graveyard

by Heather Quinlan

On December 12, 2023, New York State Assembly members met on Staten Island to tour a shopping plaza. “I hate coming here,” admitted their guide, David Thomas. “This is just desecration.” Yet David—along with his sister, Ruth Ann Hills—have returned time and again as a quest. “I didn’t ask for this burden,” David said. “I wish it had been somebody else. But that’s not the way it is. It’s a part of my history, it’s a part of American history. So I won’t abandon this.”

David and Ruth Ann’s third great-grandfather, Benjamin Prine, is buried here, beneath what is now the 1440 Forest Avenue Shopping Plaza. For nearly a century, this was the site of Cherry Lane Cemetery, the final resting place of 90-1,000 formerly enslaved and free African Americans. They came from New York, New Jersey, and as far away as the Carolinas. Many had worshipped at the Second Asbury AME Church, which was torn down in the 1880s. The cemetery remained long after the church but attempts to mark the graves were vandalized. By the 1950s, the cemetery looked like a vacant plot of land—and it was in the way of a quickly expanding commercial district.

You can talk about politics, you can talk about anything you want to. But this is personal to me, because my third great-grandfather was a slave. His mother was a slave. Children in my family were slaves, and I just think it should be recognized.

Ruth Ann Hills

But municipal maps proved Cherry Lane was a cemetery. Developers knew this plot of land wasn’t vacant. They just didn’t care. Labeled “African,” and seen as “other,” the cemetery was not protected against development. In 1954, it was sold for $1,000. Developers built a Shell station, then a shopping plaza. The bodies were never moved.

There’s babies buried there. People’s families are buried there.

David Thomas

And, it’s like, no one knows about it. It’s thrown under the rug. And in this case, paved over.

I’m a fourth-generation Staten Islander and knew that shopping plaza well. But I was shocked when I discovered it had been a cemetery. When I first read about Cherry Lane while researching burial grounds in New York City, I was determined to find out more. My upcoming documentary, Staten Island Graveyard, is now in production.

When I began researching, I hoped to connect those buried at Cherry Lane to their descendants who are alive today. As our team scoured archival records and newspaper accounts, the name “Benjamin Prine” came up repeatedly.

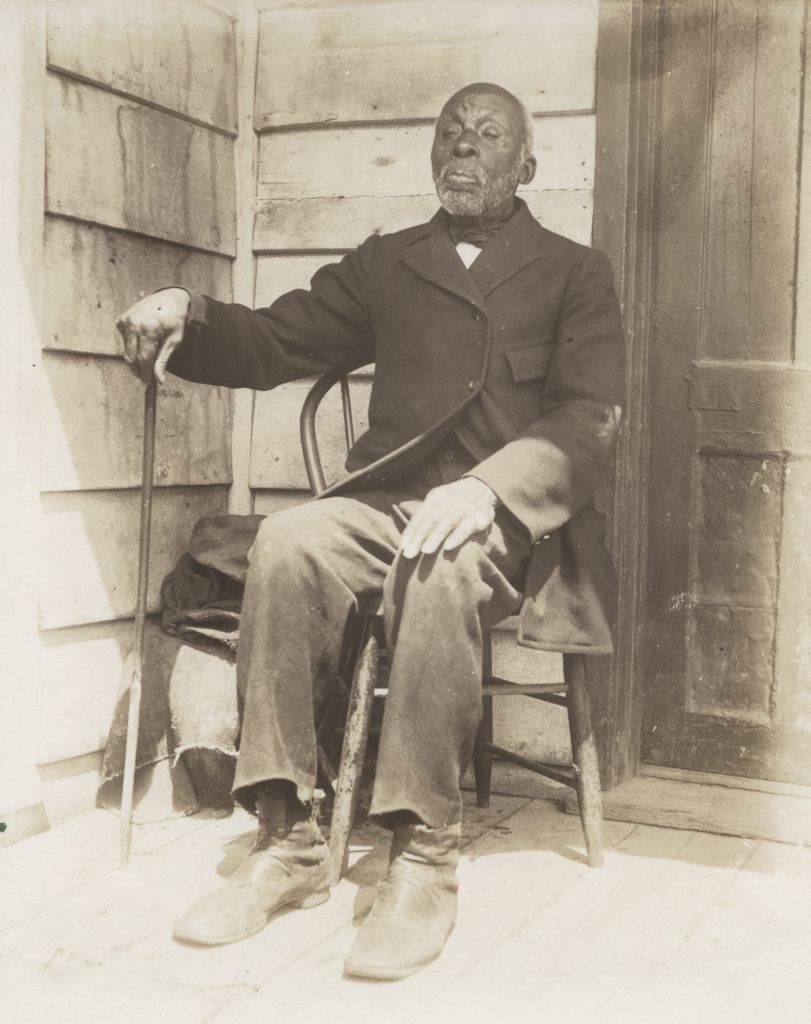

Benjamin Prine was star power. He was Commodore Vanderbilt’s childhood playmate, built fortifications during the War of 1812, drove Staten Island’s first stagecoach, and lived his final days on Elm St.—named for the numerous elm trees he’d helped plant as a young man. When Benjamin died in 1900—his age estimated 99-106—he was so well-known that his obituary was printed in the New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, and even Davenport, Iowa. A rarity for someone who’d been enslaved on Staten Island.

Following this paper trail, I was able to build a family tree that connected Benjamin Prine to David and Ruth Ann. When they learned the story they were as astounded as I’d been. Like so many Staten Islanders, they’d driven past the shopping plaza countless times. Years ago, their grandmother and great-aunt had even been on the Cherry Lane Cemetery’s board, but the siblings had never heard of him. “No one ever said anything to us,” David said. “And I ask myself, ‘Did they know?’”

When David, Ruth Ann and I first met, the site had dumpsters out in the open, used as public bathrooms. A dead tree sat crooked in the front. There was no recognition of its past.

But while we were filming in 2022, that began to change. A Santander Bank manager approached David and Ruth Ann and asked how they could help. Santander has since earmarked funds to landscape the grounds around its branch as a memorial garden. They paid for the New York City Parks Department to replace the dead tree with a cherry tree. And thanks to community efforts, on May 2023, Livermore Ave., which runs alongside the shopping plaza, was co-named “Benjamin Prine Way.” This is the first time in New York City that a street has been co-named for a formerly enslaved person from New York City.

After we filmed the New York State Assembly members touring the site in December, the dumpsters were finally locked up. One week later, Gov. Kathy Hochul signed a bill that convened a commission to research how reparations can address the persistent consequences of enslavement. This is part of an ongoing look into how legislation can help transform spaces like Cherry Lane Cemetery. Now, through the collective efforts of family, community, activists, politicians and even a financial institution, Cherry Lane has grown into a grassroots movement.

Most did not know Cherry Lane’s story but have been galvanized into action by David and Ruth Ann and the national coverage Staten Island Graveyard has garnered. Cherry Lane is today setting the blueprint for sites in a similar condition. Its revival will also help right the injustices that have taken place for decades at this site, unbeknownst to the family members who are only learning of it now.

“As African Americans, burying our dead was a revolutionary act,” said Peggy King Jorde, a Cultural Projects Consultant who worked at the African Burial Ground Memorial in Manhattan. “So when I look at this site I see a revolutionary site. It’s a battleground. And this country preserves battlegrounds.”

We really do need to look to the past to understand where we are standing right now.

Debbie-Ann Paige, Historian & Genealogist

And then, how do we use that information to move ourselves forward.

More Exploring Hate stories about Black history in America:

Today in History: Repairing a Racist Nation

In honor of Black History Month, The Rev. Dr. Jacqui Lewis, Senior Minister and Public Theologian at Middle Church in New York City, reflects on what becoming an antiracist society really entails.

Today in History: Reflection, Celebration and Repair

A Black History Month essay written by Racial Justice Advocate, Eric K. Ward