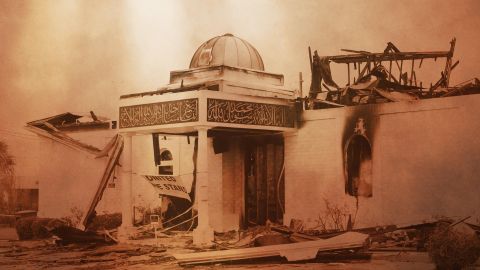

Rachel Raney (Director of National Productions, PBS North Carolina) leads a conversation about the hate crime that took place in Victoria, Texas. Members of the mosque and the filmmaker talk about the tragic events and the path for healing. Our panelists: Li Lu, filmmaker; Omar and Lanell Rachid, film participants and former members of the Victoria Islamic Center.

- Good evening.

My name is Rachel Raney.

I'm Director of National Productions here at PBS North Carolina.

I'm also the executive producer of the documentary series "Reel South," and I have spent a good part of the last three years helping to bring this incredibly powerful docuseries, "A Town Called Victoria," to public television.

Thank you so much for joining us for this special preview of the program, part one of three.

You know, when we first started working on "A Town Called Victoria," I could not have imagined the events that would unfold right as this series is being released, or that Islamophobia and antisemitism would be significantly on the rise here in the United States.

Sadly, the news right now is filled with stories of people across America in schools and workplaces and neighborhoods who are feeling unsafe because the discourse has become very inflamed.

So tonight I just wanna create a safe space where we can discuss community, interfaith connections, marginalization, and most importantly, healing.

I have some very special guests with us this evening.

Li Lu, producer and director of "A Town Called Victoria" is here.

We also have Omar Rachid and his wife Lanell Rachid, who are former residents of Victoria and members of the mosque, you met them in the film.

And I wanna thank them for being here with us.

Good evening, welcome.

Li I would love to start with you, and ask you, I mean, this was such an epic undertaking, I mean, really, six years in the making.

Why did you decide to tell this story, the story of Victoria?

Could you share that with us?

- Sure.

Hello, everybody.

Well, I grew up in a town nearby called Sugarland, Texas, and the night that the fire had occurred, I was just inundated with so many messages from people that I went to school with who had either connections to this community or a deeper connection with this congregation actually.

And so when this happened, it felt like it was happening in our collective backyard in a way, like this was happening in my hometown.

So that really gave me a sense of responsibility and also passion to seek out how this story came to be and follow it through the course of the trial and also the rebuild of the mosque.

- Li, maybe you could share with us some of the challenges that you faced in the many years that you were working on this program.

- I mean, our project was very special because it's kind of an independent series and you don't see a lot of those out there.

It's either features or short-form content.

When I started to film this with also my producer, Anthony Pedone, who is a Victoria native, he grew up there, we really saw that the story became so vast, and also the responsibility of portraying an entire community portrait really heeded us to get as much canvas space as possible.

So that's where we landed with the series format, and getting a series made in independent conditions is a challenge for sure.

So I think that was definitely a challenge.

And also the challenge was just to keep the story going and to be there for every beat of it in a way, 'cause it's definitely a story told in present tense, as you'll see especially in episodes two and three.

- Thank you for sharing that.

You know, you made a statement that I read that I actually found quite profound, Li, and it was that, you know, despite significant demographic changes that are happening across the country and in towns like Victoria that have made America, even our small towns more diverse, that communities often still lack what you called cultural integration.

And I would love to hear you talk a little bit more about that.

- Well, yeah, I mean, I think if everyone can think to their own community, how well do you know your neighbors?

Do you know the names of people on your block?

Do you know who your city councilperson is?

You know, have you visited your local mosque or synagogue or any gathering of people who are very unlike yourself just to say hello and get to know them?

I think that's pretty much every community in America.

So what you see here in Victoria truly is a microcosm of every community that there is to be, for better or for worse.

- I wanna encourage the folks that are still with us here for the conversation to encourage them to put questions into the chat, and I hope that we'll be able to get to those, because I'm sure that folks have a lot of questions for you, Li, and for Omar and Lanell.

Li, I wonder if you could share something that you did not expect to get out of this whole filmmaking process of "A Town Called Victoria."

- Well, it's a wonderful surprise to have so many great people in my life now, you know, Omar, Lanell, Abe and Heidi, Dr. Hashmi.

You know, all the folks that you see in our series that I've really grown a relationship with, I feel like these are just incredible people that I care about in my life, and we are part of a family that's been bonded by this whole experience together.

You know, I get invited to weddings and to events all the time, sadly some funerals in this six-year process of making this film too.

But that to me has been the biggest and best takeaway from this whole journey.

- Definitely gonna have some more questions for you, Li, and I'm sure the audience will as well.

But I wanted to go to Omar and to Lanell.

Welcome again this evening.

So glad that you could be with us.

Folks probably don't know that you're kind of on the road, kind of touring with the film over the last few weeks, which is I'm sure just people are really delighted to be able to meet you and talk with you.

I wanted to ask you, Omar, if you could share with us, why were you willing to be part of this film?

I mean, I've always been so moved by your authenticity and your vulnerability that you brought to the project.

- Well, I mean, I obviously thought that, first, quite frankly, I was intrigued that she was wanting to do a documentary about the event.

But at the same time, after thinking about it, I thought it was the right thing to do to bring about awareness, first about hate crime, and then secondly how hate crimes, no matter who is impacted, how it really impact that community.

And in some cases it impacts individuals on a personal level.

And I thought that the story really needed to be told so people can, across the nation and across the world as they watch it, they can see that hate crimes, you know, have a negative impact on communities, but at the same time, you can have also a recovery and a positive outcome.

I felt it just simply was the right thing to do.

And you talk about vulnerability.

I think credit goes to Li for really putting me and Lanell and other members of the Muslim community at ease, because, you know, when you do a documentary and you basically have Li and her cameraman following you for about, you know, 1,000 hours, you have to basically give it your, you know, your 100% and also be vulnerable and authentic.

And she was able to basically really give us that feeling that I can trust her with her being around us, sometimes it seemed like days at a time.

But she was able to really give us that comfort level.

- So, Li, let me come back to you, 'cause I'd love to hear a little bit about, how did you approach developing relationships with the folks in Victoria to, you know, to Omar's point, to have them feel that comfortable with you while the cameras were rolling in some incredibly intimate moments with them?

- Well, I think, you know, we spent so much time together, as Omar mentioned, sometimes it did feel like days in a way.

And, you know, I let my curiosity lead the sort of journey of what we did on this series, like what we filmed, what questions we asked, and who to talk to as well.

And, you know, I think they were all surprised that I kept filming after the initial GoFundMe had become very successful and also the rally had happened as well.

But I think it was because at a certain point they understood that I did care about how this mosque was gonna get rebuilt and what the results of this trial would be, 'cause that for me was the true story of everything, not just the quick headline that came from the night of the fire itself.

So I took the time, in 2018 I was more in Victoria than I was here in my home in California, you know?

Because I just felt so much was happening and I felt a responsibility to be there for a lot of it.

- I hate to use the word embedded, but you definitely were.

I know that you spent many, many weeks and months over the course of making the film in Victoria, and I think it really comes through in the relationship with the community there.

- Rachel, can I say something?

- Please.

- I think Li did a great job of integrating in our everyday life.

In other words, not only just interviewing with us, but just socializing with us.

Understanding, you know, breaking bread, talking about our families outside of this whole picture.

That's where the comfort came from, was that we felt almost like family, you know?

Li talked a lot about her family.

We felt like we knew more about her than sometimes anybody else that was in our house all the time.

So I think that relationship got really connected for us, and that's what made it easy to tell the story, made us feel okay to be vulnerable.

- Omar, you had a line in the film where you talked about that you were really hoping for a silver lining, but that even before the authorities came forward with the information, you felt that you knew that the fire had been intentionally set.

And you had this, I mean, I don't think somebody could have written it as powerfully as you said it, that it felt like an eviction notice.

And I was just wondering, for you, what changed for you when you found out that the fire was intentionally set?

- It was, I guess, a validation of what I thought all along, because it's not that only Dr. Hashmi was looking for a silver lining.

I think there were also members of the community at large, were not necessarily looking at it as a silver lining, they were basically looking as another excuse for the fire.

I mean, I had people in the community at large tell me to my face that, "Oh, we think that the fire was caused by a cigarette because you have a lot of your members, they stand outside and smoke cigarettes, or maybe y'all left the grill because y'all like to grill outside.

Maybe y'all left the stove in the kitchen."

So there were a lot of doubts, or at least members of the community at large, they didn't really wanna confirm or at least cross their mind at the very least, you know, the arson to cross their mind.

That never really happened.

I have never heard it from any members of the community saying, "You know, could it be arson?"

You know, they were basically shooting for something else as a cause of the fire.

And the reason I felt it was arson is because when Lanell and I showed up at two o'clock in the morning and we watched the fire from across the street, there were three large fires in that building, on the right side, on the left side, and right in the middle.

I mean, I have gone, when I was a volunteer and a board president of the American Red Cross in Victoria, I have gone to house fires and I have seen how they start, or I have seen them, how they are engulfing a house, if you will.

I have never seen a fire basically as big as the one I witnessed at the mosque.

- Right.

Lanell, talking about kind of the community and the ways in which people reacted to the fire, I love the story that you shared in the film about your grandmother, and that when she first met Omar she thought he was Spanish.

And I do know a lot of Spanish folks or Latino folks named Omar, by the way.

But that when she found out that he was Muslim, that, you know, of course, it brought up some fear for her because of 9/11, September 11th.

And I was wondering if you could share with us any ways in which you think that non-Muslims could respond or intervene when we see that kind of stereotyping of Muslim Americans?

- Well, I think it's a delicate subject, obviously.

And even with my grandmother today, who adores Omar, by the way, she loves him to death.

But she still has always, because her news, her reality of life is from the news.

She's 95 years old now, so she gets on the internet, you know, but she's not one to go to research.

So I think today, even today, you have to do it, like I always say, eating an elephant is like eating it one bite at a time.

You know, you can't look at the whole big gamut of the picture because it's too much.

So, we'll talk like simple things.

Like she's asked, "Is Jesus in the Quran?"

And so we go through and explain, "Yeah, it's in the Quran," and we give her information.

So it's kind of like a little information at a time helps kind of break that barrier between being fearful of that religion and really understanding what the religion is about.

That's kind of how I've, even non-Muslims besides her, you know, that have asked me many questions, like do you have to cover, you know?

And although I'm not Muslim, I'm still Christian, I participate quite a bit in the mosque.

But they treat me just like they treat their own family, you know?

Which is beautiful.

- You know, the one thing which is really interesting when you talk about people knowing a Muslim on an individual basis, but then at the same time have this Islamophobia in general.

I mean, I had been a member of the Rotary Club in Victoria for 22 years, okay?

And at the end of every meeting we conclude, and everything we think, say, and do, is it the truth?

Is it fair to all concerned?

Will it build goodwill and better friendships?

Is it beneficial to all concerned?

And with some members, this is just going through the motion.

'Cause I have had Rotarians say to my face that, you know, "You are a Muslim," or "Your only problem is you are a Muslim."

So even Rotarians who are supposed to be and hold themselves to a higher standard, if you will, because civically, most of the Rotarians typically are leaders within their community.

But even in the Rotary Club it was an issue.

And some of our Rotarians are highly educated.

There are doctors, there are lawyers, there are accountants, but they still had this fear of Muslims.

I think I was probably the only member that joined the Rotary Club.

There were three Rotary Clubs in Victoria.

In fact, Dr. Hashmi was president of the Sunrise Rotary Club.

I became president of my Rotary Club later on.

But I think I was the only member, I think from the time I submitted my application to the time that I was invited to watch the video, the mandatory video to join Rotary, I think my application took more than two months.

So I think even maybe the person that was in charge, who was a lawyer at that time, maybe he was, you know, trying to consider whether we need to have this Muslim in our club or not.

And because, I mean, even the guy who actually recommended me to join the Rotary Club, he was surprised that it had taken that long.

- Hmm.

- And then the same guy who actually showed me the video is the same person who made derogatory comments about Muslims to my face at the Rotary meeting.

- Who showed you which video?

- How to be a good Rotarian.

- Oh, right.

- It's a initiation video, if you will.

- Right, thank you, yeah.

- And, you know, I was probably one of the most active members in Rotary.

I've attended and participated in all the fundraising.

I led the big fundraising every year.

But yeah, it still was not satisfactory to some of the Rotarians.

- Well, I wanted to ask you about that, because, you know, we all learn, or, you know, I think we're taught at least that freedom of religion is a foundational value in American democracy.

It was one of the founding, you know, it was part of the founding of our country, right?

As people who were escaping religious persecution.

And of course, it's protected by the First Amendment.

And some people might not realize that Islam is the third largest religion in the United States.

And so after this happened, the arson and it was proven to be a hate crime, did you feel that you could practice your religion freely after this happened or discuss your religion or identify as a Muslim with people that maybe you didn't know that well or that you had just met?

- Yeah, my behavior did not change just simply because of the hate crime.

My behavior did not change at all.

I mean, I was still participating in community events.

I was still going to fundraisers.

In fact, I worked on a new nonprofit organization.

I was one of the founding members until the day I left Victoria.

And so I did not change my behavior, whether it be on a personal level as far as community related or on the religious side.

I just continued to be me.

And even when derogatory comments, discriminatory comments were made, whether be it in the community at large or the Rotary meeting or even sometimes at my place of work, I just brushed it off and just continued on.

You have to.

I mean, because if you let it really get to you, it destroys you.

And I will admit, I have gone through some difficult times and it was not always, you know, peachy, for the lack of a better term.

- I'm wondering how you attempted to heal on a personal level after what happened.

- I think... My mother has always told me that, she used to always tell me that you don't wear Velcro, so nothing sticks.

And the other person who helped me through it all is right here sitting right next to me, Lanell.

And I would express my frustrations or my disappointment sometimes in people that I had known for a long, long time.

And, you know, just bouncing and let her basically be my sounding board and let me kind of cry on her shoulder, if you will.

- We spent a lot of time traveling too.

We started kind of making an effort to get out of Victoria, you know, like go to the nearby cities, because you have to get away from the environment you're in to kind of deescalate so that the next work week you could function again, and we spent a lot of time doing that.

- And, you know, continue doing the work I did, whether it be on the professional side or on the community side.

I just continued to do what I've always done and just kept myself busy and kept focused.

But, you know, sometimes, like I said, you get down and you just have to, you know, lean on the people in your life.

And Lanell was the closest person to me, she understood my personality, my chemistry, my mental makeup, if you will.

And so, you know, you heal a little bit at a time.

- You know, Li, I wanted to ask you as well, because there's a lot more awareness these days of, you know, that documentary filmmakers spend months, years working on films that deal with sometimes very difficult topics.

And how did you kind of take care of yourself and kind of just move forward as you were making the film?

- Honestly, the answer is not very well, I think.

You know, so much of this is trying to do a lot with very little sometimes.

You know, I think it's a big thing when documentary filmmakers, especially ones that do care about the participants in the community, have to take care of themselves in a way, you know?

And a big thing that I have learned in the process of this is to hopefully make some more space for myself in other things going forward, because it does take a toll when you know that not only are you trying to do right by this community, but by the story and the bigger moment that you're in as well, to make sure that the story can be evergreen in a way so that the truths that are within can sustain itself for years to come.

So, I mean, it's not easy.

There's not a playbook for this, and we all know that.

Not only mental health, but also how we support ourselves as documentary filmmakers over year-long projects is a conversation.

You know, this issue of labor right now is also very much still in the forefront.

I'm really glad that the actors got a great deal yesterday.

But it's an ongoing process to sort of see how best you can take care of yourself while you take care of others.

- We've got some questions coming in from the audience, and I definitely wanna go to that.

But before that, I would love to hear from from all three of you, what is something that you really hope people get out of watching "A Town Called Victoria"?

What do you want the audience to take away from this story?

- I mean, my answer I think answers some of the questions that I see coming through right now.

I think, you know, unfortunately we're in this time where we are seeing vandalization and hate crimes occurring to both Muslim and Jewish communities, and I think unfortunately the story of Victoria has sort of become an allegory in a way, or perhaps a roadmap for communities to see what they can do right now.

And if anything, I hope the series showcases that, you know, to go to a rally or to give support for someone in the moment of that instance, that's very helpful.

But what is even more helpful is an ongoing, long-term sustaining relationship with folks within your community.

Because as you'll see in the story, what happens a year after or two years after the incident, you'll see a lot of folks still struggling with a lot of the sort of ramifications of the hate crime.

So how can we focus on preventing harm?

How can we focus on increasing empathy and understanding between people?

Because I think it's our collective future that's at stake.

- For me, I think it would be, I'm a believer of always trying to learn.

And I think that it's really important in your community to find people that are different than you and learn something about them.

Put your biases aside, put what you see on the media aside, don't be afraid, and really step over that line and get out of your comfort zone and learn what you can about those folks, because they are pretty much gonna be the same as you.

There's a lot more similarities than there are differences, but for whatever reason in our society, we've created such differences, and we value difference more so.

And I feel like if we would just start valuing the similarities, we could be a much happier community.

That's just my take on that.

- Well, for me, I hope people will walk away understanding that Muslims are not a threat and we are contributors to the community where we live.

We are contributors to the community at large, in a professional way, in a community way.

We volunteer, we give of ourselves, we donate.

We are Americans and we have the same aspirations as every other American.

Just because we practice a different religion that most people think is different than being a Christian or different than being Jewish.

The three religions are Abrahamic religions and they are related, there are similarities.

We pray to the same God.

And yes, there has been some radical Muslims causing us Muslims some heartaches, and these Muslims don't represent the true Islam.

And not only that, I have said it before that the number one victim of radical Islam or terrorists, if you will, hiding behind the religion, which Islam totally condemns, the number one victims are other Muslims.

But, you know, the documentary, it ought to highlight, and at least for people to walk away from, 'cause it does highlight, is that we are a member of the community, we are Americans like everybody else, and we ought to, you know, respect everybody, just as we respect everybody's political opinion, we ought to respect everybody's spirituality and the religion they wanna practice.

- Somebody's written in the chat a question that I think is very relevant, and, you know, I think it's based on a very moving scene in the film where some of your Jewish neighbors, in light of what happened at the mosque, reached out and offered up their synagogue.

They came to your services in the temporary location.

And so somebody has asked, how do you think that Muslims and Jews can come together here in the US in the current atmosphere, kind of following in the example of Victoria?

So what can you teach us as things have become quite- - It can be done.

Absolutely, it can be done.

In fact, in many communities, they have interfaith communities, where Christians, Jews, and Muslims and Buddhists and they all come together for the betterment of the community.

But in today's environment, it is totally possible to... My relationship with my Jewish friend has not changed.

In fact, I had breakfast with my Jewish friend this past Monday.

We were at his house three weeks ago for dinner.

I went to breakfast with him another time about two weeks ago.

My relationship with my Jewish friends has not changed.

And I think, you know, if we think about each other as friends and as relatives, I have my former Spanish teacher at the Victoria College who is actually Jewish, and we always called each other cousins, because we are.

Religiously speaking, we are cousins.

And we can definitely get along.

We can definitely, you know, find a way to not only get along, but also I think if you take people in today's environment, if you take people from both sides that are not necessarily driven by the anger, I think we can find a track to peace.

I really truly believe that.

- Me personally, I think it comes from the top.

Leadership needs to show and set the example.

And I think if a Muslim leader and a Jewish leader can be at the table together in each community, whoever they are, and say we as a community wanna be a team, then the people in the in the community should be wanting to be a part of that team.

But if we don't do that, we have no examples, it's kind of like kids, if they don't have an example to follow, how are you gonna fix the problem?

That's the way I could see it changed.

- You know, speaking of reaching out, there was a question from someone here about Marq Vincent Perez's parents and if the community had reached out to them after the trial and the sentencing.

And I don't know if you all know anything about that or not, but somebody had asked about that.

- Well I think Li knows more about- - We will see in episode two.

Episode two begins with the congregation reacting to the fact that Vince is the suspect.

As soon as he was identified, Dr. Hashmi and the congregation basically said, "We forgive him and our thoughts are with their parents in this difficult time."

That happened immediately after, you know, the revelation of the suspect.

So I think there's always been messages of comfort and sort of a sense of understanding that the parents didn't do it, and to the family that's also hurting, that they're in a tough situation as well, and they've been so gracious to do that.

- Thank you for reminding me that folks haven't seen all three episodes yet.

They've only seen the first one.

And I cannot encourage folks more strongly to tune in and to watch episodes two and three, which just will take you even deeper into the community and into the rebuilding of the mosque and the trial of the suspect.

And it's just, you know, really, really worthwhile.

What else, Li, do you want to share with us about the other two episodes that wouldn't be too much of a spoiler alert?

- I often say, like episode one is the promise of community, episode two in a way is the failure of community, and episode three is the reality of community, because you'll really see everything that happens, from having the arson to no mosque to the rebuild of a new mosque and what it was like to endure that time, you know, what the congregation and the community had to sort of survive and learn together through.

I think we go really deep into who these individuals are in episode two and three.

That's kind of what I'm most proud in this series, is you really get a sense of who Omar is, who Lanell is, who Abe is, who Heidi is, who Dr. Hashmi is, who these people are as individuals, versus, quote unquote, like what group they belong to in a community.

Because, you know, we're all individuals at the end of the day.

And yeah, I think it's also this inside look as to, you know, unfortunately we see these kinds of headlines every day.

And what the series does, I hope, is to showcase that there's such an iceberg below of ripple effects in a community when something like this happens, and to the effects of which I think the folks in Victoria are definitely still experiencing now because of this event, even though it was six years ago.

You know, it's definitely become something that has been quite a point in their timeline, the community's timeline in history.

- That is one of the things that I absolutely love about documentary film, is that long after the news cameras have packed up and gone home, the idea of going so much deeper and beyond the headlines and really telling the story that unfolds over a long period of time.

Somebody has asked us, speaking of a long period of time, about the children in the community.

And, you know, did you see a shift in the events that happened with the arson, with the suspect and the trial, in the young folks in the town, or were they maybe not really paying attention as much?

- I think this was the formative event in the young people's time, you know?

Especially for the ones that attend this mosque.

It's amazing how many of them are studying law, public policy, going into service in very substantial ways because of this incident.

You know, one of them now is a city council member in a major city.

Like, this was for many, many of them a formative, life-altering event for them.

And I think for a lot of the young people in general in Victoria as well, I feel if they're tuned into the undercurrent of why this happened, it really changed their participation in terms of, you know, serving the greater community in the greater moment as well.

Yeah, I'm curious, Lanell, if you've seen that.

You know, Lanell used to be a teacher in Victoria and she had a nonprofit that supported local grade youth and has a great finger on the pulse in terms of what young people in Victoria are like.

- Yeah, I think it allowed kids to, you know, I'm a believer of allowing kids to ask any question any time.

And at that time I was running a nonprofit and we did a summer program where we had kids from all ethnicities and cultures come together.

And sometimes the questions came up, you know, why you don't eat meat, some of 'em would say, 'cause some kids didn't eat that.

Or why don't you eat pork, you know?

And so it allowed them to feel comfortable in engaging in these conversations, without their parents kind of dictating what they could hear, or I don't wanna say hear, but kind of overshadow the actual event.

And so I was lucky enough to see some positives come from that, you know, that kids could communicate with one another and not feel pressured to decide if they wanted to believe their story or not, kind of thing.

It definitely affected the kids in the mosque I would say, for sure.

- Yeah.

And the other thing too is that even not only the kids but also the adults, the parents of those kids or even the other adults with no kids, like myself or Dr. Hashmi, that there was a concern before the arrest at the very least, because we didn't know basically if there are any other motives behind it.

So a lot of the parents for a while, in fact up until the arrest, some parents didn't show up to the mosque, especially the ones with young kids.

And the other adults, like I, myself, basically I changed the way I traveled to work, the time and where I parked my car, what time I leave the office, until basically things got better when the arrest was made.

But I think the younger kids, especially the ones that were maybe teenage or early teenage, I think they still have a good memory of it, and I think as Li alluded to earlier, it was a formative kind of experience.

And I think today, in today's environment that we spoke about earlier, there is that fear again, because it seems like Islamophobia is a punching bag again, and whether it be on the political stage or on the media.

So there is that fear, and rightfully so, because of the increase of Islamophobia.

And so I think there are gonna be some parents, not only in Victoria.

I mean, I know in some areas in Texas where the Muslim community is taking precaution, and I'm pretty sure families probably with small kids, they may shy away from religious activities at their respective mosque.

And we certainly in Victoria are taking the necessary precautions to ensure the safety of our congregation.

So it seems like, you know, we are reliving at least the Islamophobia that came up on the political stage back in 2016, and now we basically see it again in the media all over again.

- I'm really sad to hear that, because right when you need your community the most, people are feeling like they can't get together or can't gather in meaningful ways.

That's quite upsetting.

Well, I really wanna thank you all for being with us tonight.

We're kind of at the end of our program here, and I just really, again, wanna say I really hope that people will tune in and watch the other two episodes, because it's quite a story.

And, Li, you have so deftly and artfully crafted this, you know, into such an incredible look at this one community.

So many thanks to you, Li, and to Omar and Lanell for joining us tonight and sharing this difficult story and the amazing film.

I wanna thank all of our viewers tonight and folks that put questions in the chat and stuck with us through the conversation.

Thank you so much.

I also wanna thank our partner at the RiverRun International Film Festival.

And the engagement doesn't stop here.

We have a short interactive survey about the film and about this event, and it's been in the chat here a few times, but it's you text Victoria to the phone number [415] 223-8013, and you will get an email after tonight in the next few days.

You'll get that information in the email and a link to this recorded conversation if you'd like to share it with someone or if folks had to duck out.

And it'll also have all of the information of where and when to watch "A Town Called Victoria."

But I will remind everyone that it premieres on Monday evening at 9:00 PM on PBS North Carolina where we'll be showing the first two episodes, episodes one and two, and then episode three will be on Tuesday, November 14th at 10:00 PM on PBS North Carolina.

And of course you can watch it for free on the PBS App anytime after Monday.

And to ensure that PBS North Carolina continues to bring you these riveting documentaries, informative how-to programs, entertaining lifestyle shows, and our incredible PBS Kids content, not to mention free screening events like this, I hope that you will be inspired to make a tax-deductible donation to PBS North Carolina safely, securely at pbsnc.org.

And of course, if you are already a member, we really appreciate you and thank you for your support.

Again, just everyone, thank you for joining us.

Be kind to your neighbors and have a great evening.

- Thank you so much.

- Thank you, everyone.

Thank you so much.