ACT I

Shakespeare’s four most famous tragedies each have radically different dramatic structures compared to the others. Othello, perhaps the most perfectly structured of the group, or any group, goes together like a jeweler’s watch, each microscopic part building to the one climatic moment when Othello makes the mortal decision. Hamlet can be said to not really end; Hamlet’s indecision rather than his decision dominates the play (the play’s actual ending makes no sense except that the play has to end). Macbeth makes his fateful decision early, to murder Duncan for his crown, but he acts the part of king quite well, his doom sealed not by circumstances but by the gradual unwinding of his moral sense and with it his mind. Lear comes apart immediately—we only see the terrible working out of decisions made in the play’s first few moments, decisions which the play fails to explain. This first scene then becomes critical. It is the only glimpse we have of stability and order. The kingdom exists. Its division into three has been decided. Its division has settled a court intrigue between Albany and Cornwall (but we are prepared for Cornwall’s later treachery). Bastards are bastards, in this case physically ostracized, another kind of family division that will end up dividing far more than this family. Kent, the play’s moral compass and the only one of the three alive at the end, here merely observes, stands in for the audience in a sense.

Act I. Scene 1a

“in the division of the kingdom” (Gloucester)

Read transcript for scene

Gloucester (pronounced “Gloster”) and Kent await King Lear’s arrival. Kent wonders that Lear used to favor Albany over Cornwall, but now seems to consider them equally as he hopes to divide his kingdom equally among his three daughters. They encounter Edmund, Gloucester’s bastard son, about whom Kent appears ignorant, perhaps because Edmund has been abroad for nine years. In a jocular if ashamed fashion, Gloucester confesses his son’s begetting, with “sport in the making.” Edmund is fashionably polite, but everything he later does stems from his smoldering resentment at the status of dismissed bastard. Thus the two plots begin from the same nutshell.

Act I. Scene 1b

“Tell me, my daughters—which of you shall say doth love us most” (Lear)

“Nothing, my Lord” (Cordelia)

Read transcript for scene

King Lear enters with his daughters, their husbands and suitors, and retinue. He announces his intention to divide his kingdom, so he may “unburdened crawl toward death” and, ironically, to avoid future strife. He then insures the strife by asking each daughter to declare who loves him best. Goneril the eldest stands and flatters him outrageously. She gets her share. Regan follows with claims of greater love. She gets her share. But Cordelia cannot bring herself to false flattery, saying “nothing” instead. Lear avers that “nothing will come of nothing.” She persists, even making an argument that her love must be shared, not given to one only. Lear becomes irrationally enraged, and redistributes his kingdom. He “digests” Cordelia’s portion into the other two, declares that he will with his hundred knights rotate between the estates of Goneril and Regan, and “still retain the name and all the additions of a king.” Kent rebukes him, they have a bitter argument, and Lear banishes his most loyal gentleman, on pain of death. He is still in his mind the King.

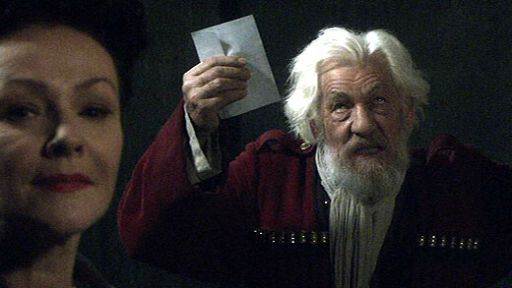

The success of this scene, and its role as a set-up for what happens relatively quickly to Lear and his two supposedly loving daughters, depends upon the level of irrationality Lear expresses here. Many directors leave Lear sensible but quick tempered. Nunn decided to have Lear mentally discomposed, almost senile, at the beginning—he has Lear fumbling with cards from which he seems to be reading his lines. This makes the scene work, but it creates a persona for Lear that must be maintained for the remainder of the play.

Act I. Scene 1c

“Better thou hadst not been born than not to have pleased me better.”

The Duke of Burgundy and the King of France enter. Lear discloses his most recent decision, and asks which of them wants a now dower-less daughter. Burgundy declines, but France accepts her, noting the strangeness of the situation, and calling Cordelia “herself a dowry.” He raises her station in paradoxes: “most rich, being poor; most choice, forsaken, most loved, despised.” Lear basically annuls her birth in his graceless adieu. Cordelia rebukes her sisters on the way out. They, alone on the stage, confer, note Lear’s recent incoherence and erratic behavior, and promise each other to make a plan, quickly.

The daughters’ suggestion of a plan never really materializes. In the scenes that follow, they seem to react to Lear’s antics rather than pursue some thought-out purpose. This becomes a bit of a motif in the play; everyone, even Edmund, hopes to see their immediate vision materialize, but successive events require adjustments, some to more ambition, some to less. We are not in Othello, where a careful plot works out almost as expected. But neither are we in Measure for Measure, where events themselves seem capricious. There are plans in Lear—they just do not go as planned.

Act I. Scene 2a

“Let’s see, let’s see”

In a soliloquy to nature, Edmund declares himself as true to nature as anyone born according to the fashion of legitimacy. He swears a personal oath to replace his brother in his father’s affections and inheritance as he pleads with the gods to “stand up for bastards.” (His tone suggests greater ambitions, to be realized.) Gloucester enters, grieving for the loss of Kent and, in effect, Cordelia. Edmund feigns to pocket a letter, noticed of course by Gloucester, who insists on seeing its contents. It appears to be in Edgar’s hand, and proposes a plan to rid the earth of their father to hasten their inheritance. Gloucester takes the bait. Edmund feigns disbelief, and so proposes a test of Edgar’s intentions which Gloucester may be placed to overhear. In a kind of soliloquy in parallel to the one opening the scene, Gloucester laments the many ways in which the world seems to be cracking. He orders Edmund to “find out this villain” and exits.

Edmund proposes that this scene of catching the conscience of Edgar will take place that very evening. When it actually happens is not clear from the scene in which it does happen—Edgar seems to have been in hiding—but it would make sense to happen before the events that are related in the next scenes with Lear and his daughters. The play thus jumps back and forth in time in ways that may be disconcerting on first viewing.

Act I. Scene 2b

“This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, . . . we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars, as if we were villains by necessity.”

In colorful language, Edmund observes that people tend to blame nature for their own faults. Edgar wanders in. Edmund feigns distress at how upset their father seems to be with Edgar, who saw him but two hours before. Edgar charges some unknown miscreant, which hypothesis Edmund gladly supports. He urges Edgar to leave, armed, and to proceed to Edmund’s chambers where they might meet that night. Edgar takes his advice and leaves. Edmund chortles at the “foolish honesty” of Edgar and their credulous father.

We might chortle as well. Gloucester in the play never loses a kind of naïveté—he is not a thinker. Edgar on the other hand displays enormous creativity in his role as mad Poor Tom, to avoid capture, and then as shepherd of his blinded father and swordsman, when he kills Edmund. Why he should believe Edmund here is anybody’s guess. The scene places considerable pressure on Edmund to be believable.

Act I. Scene 3

“By day and night he wrongs me” (Goneril of her father)

Discussing matters with Oswald, her steward, Goneril complains bitterly about the riotous and abusive behavior of Lear and his hundred knights, who act like children: “old fools are babes again.” She advises Oswald and his cohort to be cool and dismissive toward them; if they do not like it, they can go to her sisters, who feels of like mind. When Lear returns from hunting, Oswald is to tell him that she is sick and cannot receive him. She writes to her sister to hold the same course.

Some time has obviously passed. In the next scene we will find hints that it is two weeks, or two days, but surely not longer. If we have been paying attention, it comes as a surprise, for we have been set up to anticipate an evening meeting between Edmund and Edgar which Gloucester would overhear. However, time is not tidy in this play. Riotous knights of course provide an opportunity for stage buffoonery at the expense of the royal and noble class, a welcome point of humor for the average Elizabethan audience. However, that audience would also know that 100 knights may mean as many as 400 people when squires and retinue are added, meaning that only the largest and most well-equipped castles could provide for them. Indeed, we will learn later that Gloucester’s house cannot accommodate them. Queen Elizabeth and King James visited noble estates frequently with hundreds attending them, driving the poor hosts into great economic stress. Even without the knights rioting, 100 of them would be a terrible burden.

In this sense, Goneril has no right to be offended or surprised if she accepted her share of the kingdom with the stipulation that Lear “retain the name and all the additions of a king” as that would have been understood in the English Renaissance. Lear may react quickly, and rashly, when she attempts to reduce his train, but he has some justification.

Act I. Scene 4a

“Who art thou?” (Lear) “A very honest-hearted fellow, and as poor as the king.”

Kent enters, disguised, and announces himself as such so the audience knows who he is. Then Lear and his knights come in. (We are to imagine a riotous crowd, or the production will have a riotous crowd.) He espies Kent and after a sequence of questions about who he is and what he wants, all given in a rather jocular style, he agrees to have Kent serve him. Lear calls for his Fool, a court jester, but Oswald appears instead. Lear orders him to fetch Goneril. He leaves, but Lear calls him back. He gets a message that Goneril is ill, and then a suggestion from one of his knights that they are not being treated as they should be. Lear agrees to a “faint neglect” but blames himself rather than purposeful unkindness. He sends for Goneril. But Oswald reappears instead. Lear greets him with crude vituperations, then strikes him when Oswald protests mildly, after which Kent trips him, earning Lear’s praise and a tip. (This may be imagined as a farce.)

This scene is very long and somewhat digressive, making it a target for cuts in performance. It has more entertainment value than depth or development. Also, Lear will be as quick-tempered and judgmental with his other daughters here as he was with Cordelia. The suddenness of his change in attitude suggests that we are to pay less attention to its reasons than its consequences.

Act I. Scene 4b

“Dost thou call me a fool, boy?” (Lear) “All thy other titles thou hast given away; that thou wast born with.” (Lear and the Fool)

At last the Fool appears, continuing the mood. His first jest is on a common subject, his coxcomb, a jester’s peaked hat. He offers it to Kent because Kent has joined with a man out of favor who has banished his two daughters and done his third a blessing against his will. After another joke, he sings a song of advice about the advantages of modesty. Kent calls it nothing, the Fool says he got nothing for it, and asks Lear if can make use of nothing. Lear repeats what he said to Cordelia, which the Fool says is what he gets in rent. They banter on like this, the Fool harping on Lear forsaking Cordelia and giving his kingdom away, inverting his natural relationship to his daughters.

This scene must be read to be understood; the Fool says quite a few things that need explanation. The Fool is an unfamiliar stage figure now. However, at the time James I had a fool who acted much as the Fool does in this play, to amuse the king and often suffer in consequence. The Fool here however acts in some ways as the conscience of Lear, or a stand-in for Cordelia. Some have taken a view that in Shakespeare’s day the Fool and Cordelia were played by the same teenage boy actor (women could not act in professional English theaters until 1660). They are never on the stage at the same time, and one actor playing both reinforces this relationship. Against this view is the circumstance that Shakespeare had a famous comic actor, Richard Armin, who would have logically taken this role. (Against this view is that Armin would have been needed for Edgar. We will never know.) However, several prominent productions of Lear have used an actress for the Fool, including a production in 1990 with Emma Thompson playing the role.

Act I. Scene 4c

“That she may feel how sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless child!”

Goneril finally appears. She upbraids Lear for his riotous men, and for defending them. He begins to get upset: “Are you our daughter?” She then states her real intention, to reduce the size of his train, insisting as well that the remainder behave themselves. Lear becomes enraged—“darkness and devils”—and orders removal to Regan’s household. Albany (Goneril’s husband) now enters and pleads for patience. Lear produces a sequence of outbursts, including one with perhaps the play’s most famous line. Albany attempts to control the situation, but Goneril dismisses him (in effect). Lear finally blasts Goneril for the last time, with forebodings of things to come, like Gloucester’s blinding. But he still holds faith in Regan, meaning he is still not fully awake to his own folly. After Lear leaves, Albany warns Goneril, “You may fear too far,” to which she replies, “Safer than trust too far,” a nice psychological summary. Finally, Goneril sends a letter to Regan with the curious instructions to Oswald to “add such reasons of your own as may compact more.”

Without doubt, Lear here is irrational, if not mad. Much less clear is Goneril’s moral state. Lear clearly has a point: he is still a king in a sense, she agreed to the bargain, and she should be grateful for his largess. She as clearly has a point: Lear should act his age. But either the director or the actress must decide how venomous to render Goneril here. She is going to be caught up in a murderous and adulterous conspiracy with her sister that brings death to her, her sister, Cornwall, Gloucester, and Edmund, a conspiracy that cannot be justified by her reaction to Lear alone. When did it start? How much does her reduction of Lear’s train, the central fact causing his anger, come from her desire for greater power? Is she, like Edmund, evil of necessity, or does she grow into it little-by-little, in of course ways the play does not reveal?

While Goneril’s reduction of Lear’s train from 100 to 50 men is real, its more powerful role is metaphorical, suggesting a systematic reduction in Lear’s status both as a king and as a person, until he finally asks “unbutton here” in Act III, reducing himself to nakedness, or metaphorically, nothing.

Act I. Scene 5

“O let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven, I would not be mad.”

Lear orders Kent to take a letter to Regan (via Gloucester it seems). After Kent leaves, the Fool calls Lear a fool for growing old without growing wise. Lear ends the short scene with, “let me not be mad, not mad . . . I would not be mad.”

We can be said to have completed here the beginning of the Lear plot; what happens hereafter builds upon and complicates the basic elements put in play. Note the first suggestion that Lear may go mad, from Lear himself. It is a director’s decision how mad we are to take Lear at the moment he pleads not to go mad. He has already acted in ways that most would consider insensitive if not deranged. However, we have not begun full preparations for the Edmund story.