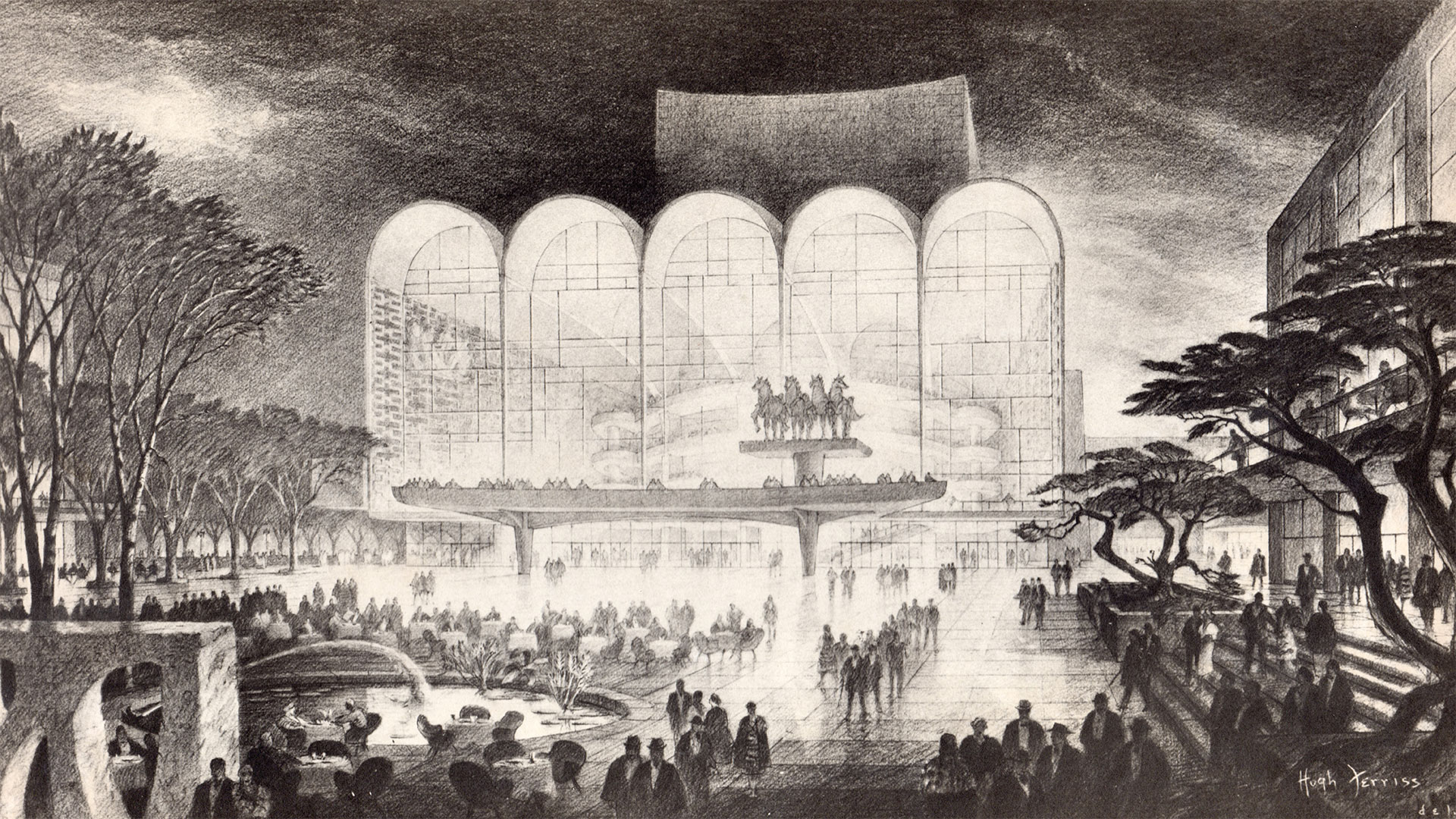

An early Wallace K. Harrison design for the new opera house at Lincoln Center. Rendering by Hugh Ferriss (1956–57). Credit: Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

The Metropolitan Opera played a pivotal role in bringing together a wide range of cultural institutions to a centralized new Manhattan home in the 1950s and ‘60s. Here, we pull back the curtain on the opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s new home.

1. The Met almost moved to several other notable New York locations

Beginning as early as 1908, the search had begun for a new home for the Metropolitan Opera. Over the years, various attempts were made to find an appropriate location and construct a new facility. Utilizing personal funds, the Met’s president at the time, Otto Kahn, bought a space on 57th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. There were also initial plans to construct the new opera house at Washington Square and as part of what would eventually become Rockefeller Center. It wasn’t until 1949 that federal legislation was passed that empowered New York City planner Robert Moses to put into motion the events that eventually led to the Lincoln Center development.

2. The scope of the project was enormous

At the time, other urban renewal projects in Manhattan spanned roughly 10 to 12 acres, but the Lincoln Center site was 45 acres, covering a three-and-a-half–block area between Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, from 62nd to 65th Streets. The new house was finally completed in fall 1966.

3. Mistakes were turned to art

Sometimes the most human moments turn into the most beautiful outcomes. Just before heading into a meeting with John D. Rockefeller III and Rudolf Bing (the Met’s general manager), Tadeusz Leski, lead architect Wallace K. Harrison’s right hand, was finalizing the latest perspective drawing of the building’s interior when a splash of paint spilled onto his drawing. He quickly added some lines, so that splotch of white paint would look like refracted light from the chandelier. In the film, Mr. Leski describes them “like fireworks.” However, this was not the traditional design that Rockefeller and Bing were expecting. But the two men loved the way they looked, and the starburst chandeliers became part of the design.

4. A historic talent opened the new house

Legendary soprano Leontyne Price was chosen by the Met and composer Samuel Barber to open the new Metropolitan Opera House as Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra. She recalls finding out about the decision: “The whole point was for it to be an all-American occasion… I was just so determined that I was going to do my country proud.”

5. Leontyne Price was locked inside the set just before opening

In a dramatic change of scene in director Franco Zeffirelli’s production for Antony and Cleopatra, a giant moving pyramid swallowed up Cleopatra, then moved offstage in the dark. But at the final dress rehearsal, as the lights came up, the pyramid was still mid-stage, stalled. The tomb wouldn’t open, and Leontyne Price was locked inside. The stage crew didn’t have enough time before Opening Night to fully repair it and ensure it would work. During the performance, the pyramid stalled again, but luckily it was far enough back to be out of sight and allow the opera to continue.

There are more facts to be discovered about the development and opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s Lincoln Center home. Join us Friday, May 25 at 9 p.m. (check local listings) on PBS to learn more.