Owning the rights to your own work must be the ideal for any creative artist, but in the nature of the show-business beast, you more usually end up owned. The first half of the 1990s was a period in which Andrew Lloyd Webber set about defying these rules by assiduously re-acquiring the rights to one of his earliest pieces, “Joseph,” and producing his next big show, “Sunset Boulevard,” entirely within the company designed to exploit him.

Even before Robert Stigwood had come along to propel Rice and Lloyd Webber to fame and fortune with “Jesus Christ Superstar,” “Joseph” had been sold by Tim and Andrew to the independent music publishers Novello for 100 guineas (about $165 dollars). When Novello had been acquired by Granada Television, Lloyd Webber kept in touch with Sir Denis Foreman, the chairman of Granada, reminding him of the little show that could still prove to be a big asset, and he was more than miffed when Granada sold Novello without telling him. It was bought in the late 1980s by a small film music outfit called Film Trax, and eventually, they asked Lloyd Webber’s company, the Really Useful Group (RUG), if they would be interested in buying “Joseph” from them, as they started to sell off various items in their catalogue.

A deal was negotiated on behalf of RUG costing £1m, and soon afterwards the executives heard from Tim Rice expressing dismay that he had not been offered his half share. RUG directors felt that as Tim had resigned from the board, not without financial advantage to himself, and that the rights had been offered to the board, he was no longer part of the equation. Andrew says he abstained on the vote. There was nothing in writing with Andrew, but Tim had always, not unreasonably, understood that when the copyrights on their collaborations came up they would have an equal share. Andrew at first denied any such understanding, but after thinking it through, readily agreed as long as Tim paid half of what RUG had paid to Film Trax.

The papers were drawn up and the business well in hand when Tim decided to withdraw from the purchase. There was nothing much happening with the show and the price was more than he could afford at that time. Within a few months, “Joseph” was re-launched in a spectacular new production at the London Palladium with pop teen idol Jason Donovan — an Australian TV soap star who was branching out — ensuring a siege at the box office.

It wasn’t long before Tim Rice changed his mind yet again about his half share in the once-little musical, but RUG argued that, because of the Palladium success, the show now had a totally different value, and Polygram, as major shareholder in RUG, vetoed the request.

All of this annoyed Rice intensely, but as usual he presented a sanguine face to the world. “In a funny way, I think I’m better off not having my share because I don’t have to get involved in any of the productions, or run any risks. And I’ve also been able to be as awkward as I like — I still have an artist’s veto — and all I’ve done since then is collect the royalties.”

Which just goes to demonstrate how a charming, innocent collaboration could become, in time, a source of resentment and enmity between the two people who wrote it. The show had become a popular stalwart of school, college, and touring productions around the world. In Britain, the producer Bill Kenwright had a version (fairly tacky, when I saw it) on the road for years on end. But it had never been a West End hit.

Joan Collins But on June 12, 1991, a production costing £1.5m opened with advance ticket sales of £2m and climbing. The cast album went straight to the top of the hit parade, as did Jason Donovan’s beguiling, Caribbean-flavoured version of “Any Dream Will Do,” and the show broke all Palladium box office records before it closed in January 1994. When Donny Osmond led the American cast in the same production, “Joseph” was discovered anew on this side of the Atlantic, too.

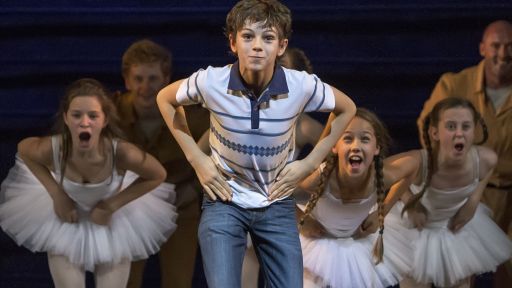

The show had grew and grew in a remarkable display of what the leading London critic Milton Shulman called theatrical parthenogenesis — the development of an egg without fertilization. The 20 minutes at Colet Court had stretched to 40 at the Edinburgh Festival in 1972, an hour in the West End in 1973 and now this two-hour, camp extravaganza dreamed up by director Steven Pimlott and designer Mark Thompson, talented scions of the state-subsidized theater and opera stages in Britain.

The robust simplicity of the piece has guaranteed a new life for “Joseph.” This video combines the witty extravagance of Pimlott’s stage production while deleting its more ludicrous excesses. “The show just works and everyone loves it, “says Tim Rice, “and I can almost watch it as if I hadn’t written any of it.” The revival, and this video, have resoundingly proved Lloyd Webber’s claims for its indestructible quality, what he calls “a strong core to the piece that makes it possible to hang anything on it, like an umbrella stand.”