We are blessed with eleven film versions of King Lear (including the announced release of the McKellen film). While we might say that some are better than others, each has value and interest. Indeed, a more useful distinction might be between those taking a conventional approach to the play compared to those veering into experimental waters. Curiously, the first three film versions of the play taken historically are the most eccentric—Orson Wells in 1953, Paul Scofield in 1971, and Kozintsev’s Russian version of the same year. The versions after this trio have hewed to a more traditional line, that is, they have left the plot sequence intact, they have retained the play’s key moments and lines after cutting, and they have approached the play from a more psychological perspective than a metaphysical one. All but one were shot in studios. The exception, Brian Blessed’s 1999 version, has magnificent visuals and a debt to Kurosawa’s Ran, but it gives us Lear as Shakespeare wrote it.

Some of this has to do with money. The Scofield, Kozintsev, and Blessed films began life as screen plays. The first two were shot in black and white, forty years ago; they feature long studied landscapes, hundreds of extras, and the kind of spectacular atmosphere that only film can supply. All of the films but Blessed’s shot since then began life as stage plays (one is a film of a stage play), from which a studio film version was constructed, generally for a prospective television broadcast rather than theater distribution. They are only available to us now because DVDs are so inexpensive to produce. With minimal sets, little landscape, few supernumeraries, no horses, and a kind of forced claustrophobia that such conditions often engender, these films focus on faces, minds, and words. They are therefore limited to the compass of effects such circumstances entail. They are great effects, but they are not all the play can produce. (It is in this sense that one must deeply regret the recent cancellation of Anthony Hopkins’ Lear, with an all-star cast, and a $36 million budget—the reason it was cancelled. It could have added the spectacle or operatic nature of the play back into the its psychological spaces.)

If one has interest in watching but one Lear film, we would recommend McKellen, Holm, or Olivier (in that order). However, within the constraints suggested above, these three have substantially different approaches to the play’s critical questions. An exploration of King Lear would look at all three. But, a real exploration of King Lear would watch a conventional version, and then at least Kozintsev’s Russian version and Welles’ truncated television version, to see the vastness of the possibilities. The Scofield Lear is a bit of an acquired taste—it has by far the widest range of critical reviews, from rapture to disgust. It has undeniable visual power—its debt to Ingmar Bergman cannot be missed—but Scofield’s Lear feels attenuated, almost asleep at times, and Edmund feels more like a ghost in a machine than a real character (but of course more menacing in consequence). It works for what it tries to do, and it is well worth the watch, but it is the most eccentric version of the lot. The Lear film with the greatest sense of spectacle is not really a Lear film, but an adaptation by Kurosawa entitled Ran, meaning chaos. His Lear divides his kingdom among sons, who then have an amazing 14th century war. It is free of Shakespeare’s words, but it is in many ways faithful to Shakespeare’s intentions, and the visuals are peerless. Finally, on the other end of the spectrum lies James Earl Jones, whose Lear film captures a live Central Park production. Jones does some quite sensational things in the film, but some of its interest derives from the audible audience. Shakespeare never imagined a play without an audience (he seemed entirely disinterested in his plays’ print publication). An audible audience was part of the play. So, to experience this feature of Shakespeare, you have to go to a play, or watch James Earl Jones.

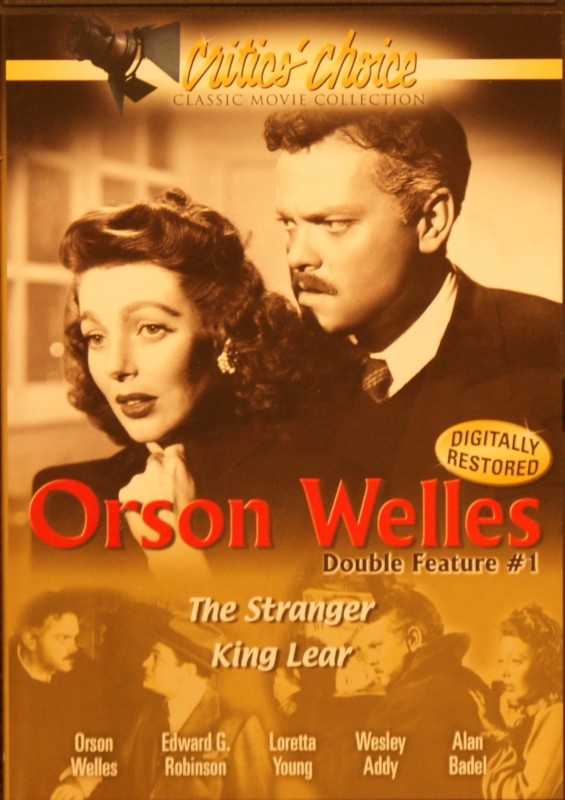

1953 Orson Welles as Lear, Andrew McCullough / Peter Brook, directors

Shot for the CBS Omnibus series in 1953, this black and white version cuts the second plot to meet the 75 minute time slot of the series. The filming circumstances are also crude—two cameras, virtually no sets, a small studio stage. But Welles makes up for these deficiencies with a riveting portrait of the aging Lear, perhaps the most clear and accessible on film. His false nose and massive beard hide his normal countenance—you may not recognize him—but the hair alone migrates into madness. No study of King Lear on film would be complete without a serious viewing of this compelling rendition. The DVD couples King Lear with The Stranger, a modest Welles effort (compared to, say, The Third Man) but one still giving the Welles’ chill.

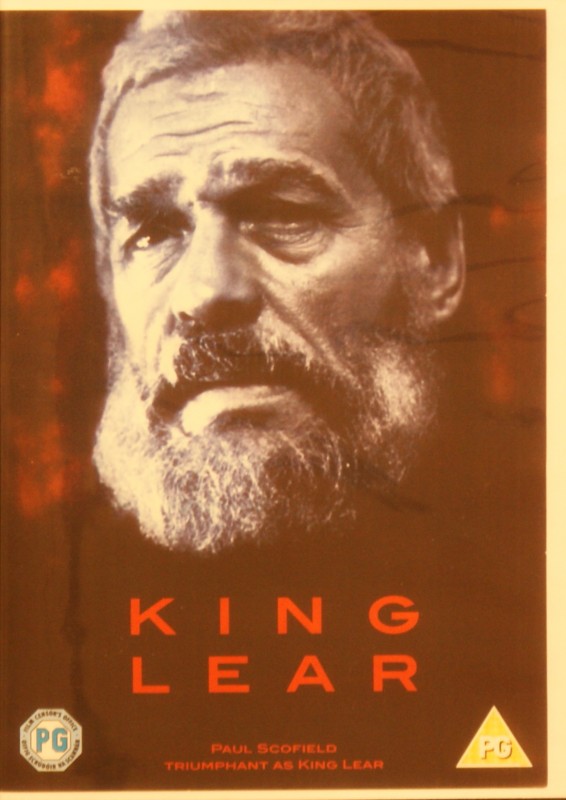

1971 Paul Scofield as Lear, Peter Brook director

Peter Brook rewrote the King Lear interpretative book with his 1962 stage production starring Paul Scofield. This film version reflects the play, but is shot in Denmark, with vast landscapes, snow, creaking old castles, and some amazing old carriages. In black and white, with an emphasis on black, it takes great liberties with the plot, omitting whole scenes and moving things around to suit Brook’s dramatic intentions. Among the omissions are quite a number of little moments that help explain subsequent ones, a feature that makes the whole play, and hence the whole world, seem to be without cause, or purpose. One must work a bit to get used to Scofield’s very subdued (or just really really old) Lear; he barely moves his lips in the opening scene. But the film is a classic. Unfortunately, it is only available in DVD in UK PAL format (which runs now on surprisingly many U.S. DVD players).

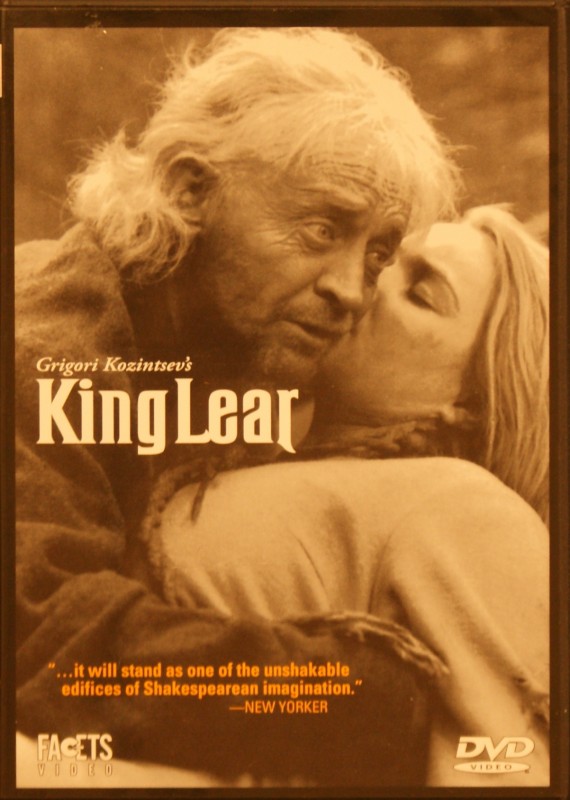

1971 Juri Jarvet as Lear, Grigori Kozintsev director, in Russian

From the first halting steps of a peasant’s foot on a dusty path that gathers itself into a peasants’ march on Lear’s castle, this black and white production announces itself as a people’s play. The people seem at the end for all the world to be capable of repairing the burning ruin of their leaders. Their leaders on the other hand are either mad or corrupt. The film thus replaces what may be majesty in other versions with the earth itself. Juri Jarvet has a shock of white hair and small stature. Unlike Lears such as Scofield and Welles, he does not fill out the screen by himself. But his rage is royal rage, his tragedy as real as any on film. Boris Paternak wrote the screen play and Dimitri Shostokovic wrote the haunting music. A small clue about Kozintsev’s meaning: at the end, over a pan of wreckage and death, the Fool plays on his flute a melody Shostokovic wrote for the play’s beginning. Music and humor and the people move irresistibly on amidst the horror of the state.

1974 Patrick Magee as Lear, Tony Davenall director

Patrick Magee played Cornwall in the 1971 Peter Brook film. He tries his hand at Lear himself in this Thames Valley production. It shares some of the virtues of Mike Kellin’s later version—Renaissance costumes and clarity of diction. And there are moments when Magee hits the mark. But the film in general lacks energy. Too many actors stand around as if lines are to be read, not acted. The cuts to realize a two-hour film also grate. The Fool virtually disappears (he is not credited), along with many lines that motivate future action or reveal deeper character traits. The early stage sets are sumptuous, but once outside in Acts IV and V the fake grass and blank sky set never changes. Rather than gather itself around some conception of the end of man (or his redemption), the ending just kind of disappears. This is a required part of a full collection, but not the best Lear with which to begin.

1974 James Earl Jones as Lear, Edwin Sherin director

This is the only film version of an actual staged production, in this case the Joseph Papp production in Central Park in New York City. It includes some actors who became famous later—Raul Julia, Paul Sorvino, and Rene Auberjonois. Camera angles sometimes bring the audience into play, but there are no stage shots from the audience directly. The audience is audible, delightfully so at times. Jones is strong, particularly in certain scenes where he is able to modulate across long speeches to good effect. The film’s length provides room for most of Shakespeare’s words, a pleasant surprise after some films that cut, cut, cut. However, its chief virtue, aside from Jones, is the sense of life given by the audience, an integral part of any play Shakespeare imagined. One may also feel the tempo of scene changes created by exits and entrances rather than fast cuts, a feature that makes some sense of the play’s difficult treatment of time.

1982 Michael Hordern as Lear, Jonathon Miller director

This film, made for television, seems the most conscious of its intended small-screen medium and the play’s stage origins. While it was shot in color, its palette is largely monochromatic, a rich black and white. The camera moves very little; rather, people move within it, suggesting relationships as much as individuals. Close-ups are very close, but always with some rhythm to a larger sense. In keeping with this spirit, no one over-acts, itself a miracle. Hordern manages a wonderful balance between age and power, the latter showing up at interesting moments rather than dominating his performance. The supporting roles are less convincing than in the top films (McKellen, Holm, Olivier), but the film’s general effect is quite moving. Its ending, so important in this play, illustrates its point; rather than dwell on death, or life after death, it stands for minutes on five faces gathered in a portrait of both.

1982 Mike Kellin as Lear, Alan Cooke director

This film’s interest lies in its commitment to Renaissance period costumes and the hearing of every word. It may come closer than any film to what audiences might have seen at the Globe in Shakespeare’s day (with allowances of course for the many sets used in the film studio). One feels great sympathy with the Fool, present at the king’s feet during the opening act, and diffident rather than arrogant in his wisdom. Edgar is captivating; his brother seems to be reading his lines. The cost, if it is a cost, comes with Lear’s madness (he seems more angry than mad) and a kind of inertia derived from the limited number of camera angles (there appear to be but two) and stationary physical blocking. The production rather concentrates on individual speech and the words. Given that most other film versions make the words hard to hear from time to time, and Shakespeare is if anything about words, words, words, we must respect this effort. It is clear, without greatness.

1984 Lawrence Olivier as Lear, Michael Elliot director

Probably the most celebrated King Lear on film, this version with Lawrence Olivier has many fine moments. Elliot set the time among the Druids and Stonehenge, giving the play a mythical quality that helps offset the obvious limitations of a studio project. Stones and flames create a sometimes mystical effect. John Hurt does a memorable Fool, Robert Lindsey skulks as Edmund, and Diana Riggs sallies forth as Regan. The ending funeral gives a kind of beatitude, the most affirming ending of the extant film set. The film loses its hold on greatness from some of Olivier’s signature mannerisms and his own age (75) that sapped some scenes that need great strength and energy (for a man supposedly in his 80’s) to work. Indeed, Olivier’s own physical weakness became the most common criticism of the film. However, this film rates in the top three of those taking a traditional approach and would reward any first viewing of King Lear on screen. (May be purchased at www.shoppbs.org. Put King Lear in the search bar.)

1998 Ian Holm as Lear, Richard Eyre director

The most remarkable thing about this fine film is the way in which Ian Holm, an actor of rather small stature, carries off the mania and raw power of the king himself. (He ironically won the Lawrence Olivier award for his stage performance.) Of equal interest is the circumstance that for the most part his every word can be heard. (Many Lear’s connect mania with speed of speech.) Eyre set the play (obviously filmed in a studio) in minimal sets and everyday casual dress, but with interesting transitions between rich interiors with torches to bare walls; angles make the mise en scene part of the play itself. The same can be said for mist and sand. The storm scene is magnetic, although at times the storm wins. Erye places Edmund’s opening “stand up for bastards” monologue at the beginning as an interior monologue while his father describes the sport in his making—a nice idea for those who do not know the play—but then cut the most important parts of the speech. One could quibble with other cuts. However, Holm and his supporting cast create a splendid Lear within the natural constraints of film itself, and films made for television on small budgets. (May be purchased at www.shoppbs.org. Put King Lear in the search bar.)

1999 Brian Blessed as Lear, Brian Blessed director

Somehow Brian Blessed found the money to mount a King Lear fashioned around the real world with real film resources far in excess of the many versions shot in studios. It has spectacular scenes, including a battle scene with hundreds who shout and clamor and roar at each other as if they were in a movie by Kurosawa. Blessed himself has a great voice and physical stature to match. He also chose a length that permits most of Shakespeare’s words to flow into the film, a treat for those in love with all of Shakespeare’s words. Hildegarde Neil provides the only Fool on film played by a woman, and she is quite wonderful at it. As with all Lear films, it has magical moments, and moments that fail. What keeps this film from the halls of greatness is its lack of motion. Blessed seems at times to be talking to himself. Scenes at times feel like sequences of stills rather than interactions among characters. And the acting at times does not rise to the level of the spectacle. Still, it is a film worth the effort to see it.

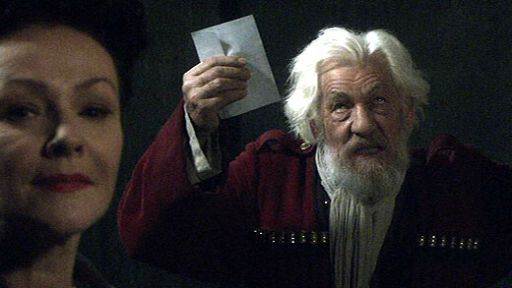

2009 Ian McKellen as Lear, Trevor Nunn director

While McKellen does Lear like it was part of himself, what makes this film stand at the top of the stairway is the work of the supporting cast. A great Lear does not necessarily make a great Lear. Without strong performances from Goneril, Regan, Edmund, Gloucester, Edgar, and the Fool, the play can sag around the towering inferno of its hero. Here we have some of the best, and in a few cases without question the best, performances on film. Phillip Winchester as Edmund, Sylvester McCoy as the Fool, and Jonathan Hyde as Kent sparkle. Each of this sextet, under the direction of Nunn no doubt, develop their characters during the course of the play in ways that mirror the disproportions of the play generally. A few details seem more annoying that not—do we really need guns—but others merit the time it takes to notice them. Check out Lear’s wedding rings, the migration of the Fool’s doll on a stick, the first time we see a sky, and the number of times a piece of paper pops out, or the man recording Lear’s redivision of his kingdom. McKellen claims the play relates Lear’s discovery that the God he prays to does not exist. One wonders if that is the only way Nunn’s ending can be read. (May be purchased now at www.shoppbs.org. Put King Lear in the search bar.)