By DANIEL ROSENTHAL

Daniel Rosenthal, author of The National Theatre Story, the definitive new history of the National Theatre of Great Britain, looks back at the original productions of ten of its most celebrated shows, as featured in Great Performances: 50 Years on Stage, airing Friday, February 14 at 9 pm.

Enter to win a copy of Rosenthal’s The National Theatre Story (2014, 800 pgs) through the Great Performances giveaway contest, now through February 17, 2014.

10 Tales from 50 Years on Stage

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967)

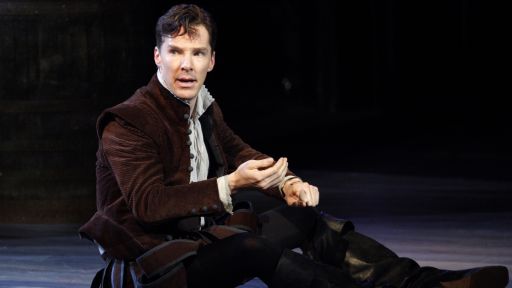

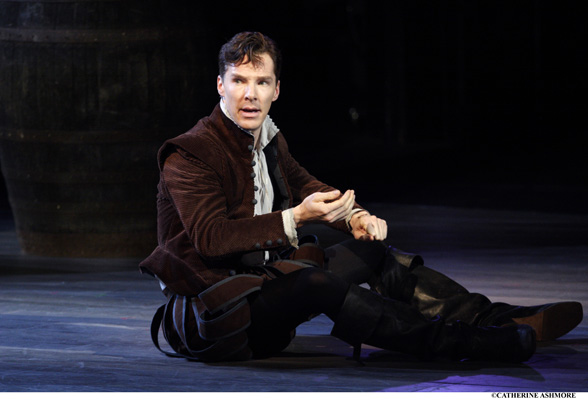

Tom Stoppard’s “existential fable” (The Observer) about Hamlet’s Wittenberg cronies opened at the Old Vic in April 1967, directed by Derek Goldby, with John Stride as Rosencrantz and Edward Petherbridge as Guildenstern (roles taken for the 50 Years on Stage segment by Benedict Cumberbatch and Kobna Holdbrook-Smith). After rave reviews from the London critics, legendary Broadway producer David Merrick cabled National Theatre Director Laurence Olivier:

“Dear Larry I am absolutely mad about Rosencrantz and Guildenstern STOP Please do everything you can to get it for me STOP Terms no object STOP You fellows can write your own ticket STOP.”

BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH as Rosencrantz in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard, in 50 Years on Stage.

Merrick secured the rights and Goldby recreated his staging that fall at the 1,400-seat Alvin Theatre (now the Neil Simon), with Brian Murray and John Wood as the title characters. The New York Times’ Clive Barnes greeted “a most remarkable and thrilling play”, which went on to win Tonys for Best Play, Producer and Set and Costume Design.

Outside the Alvin, a few days after the opening, a woman had asked Stoppard, then aged 30, what his play was about.

He replied: “It’s about to make me very rich.”

Reported in the next day’s newspapers, this remains Stoppard’s most celebrated (off-stage) one-liner – delivered, he told me, only “because I was sick of people asking me what the play was about. It sounds triumphalist, when in fact I was just snapping at her.”

No Man’s Land (1975)

SIR MICHAEL GAMBON as Hirst and SIR DEREK JACOBI as Spooner in Harold Pinter’s No Man's Land. Photo Catherine Ashmore.

In the 50 Years on Stage segment featuring Harold Pinter’s play, Michael Gambon and Derek Jacobi take on roles originated by Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud at the Old Vic: Hirst, a writer who spends a drunken evening in his London home with Spooner, who claims also to be a successful writer – and to have seduced Hirst’s wife.

In 1975 at the Old Vic, where No Man’s Land was directed by Peter Hall, Gielgud “dried up stone dead” during the final preview, while delivering Spooner’s ingratiating, two-and-a-half-page monologue, in which he applies to become Hirst’s secretary.

Gielgud wrote to a friend of being “in terror” of drying again on opening night, April 23, “but God – or proper concentration – was with me, fortunately. Very good press all round – all a bit baffled by the [play’s] obscure passages and whatever moral one takes away – or leaves behind? But it is funny, menacing, poetic and powerful.”

Hall had found after about a week’s rehearsal that the “two old lions”, who had not “grown up [with], or subscribed to, a pause culture as far as plays were concerned”, were frequently coming to a baffled halt:

Gielgud Ralph, is that you?

Richardson Johnny, is that you?

Hall Look, it’s neither – it’s a pause.

Gielgud Oh. Right.

Richardson Well why?

Hall recalled how he would then explore “what happens in the pause, where the actor moves internally. But they simply couldn’t learn the pauses and the silences, so I actually stopped rehearsing for a week and said ‘Just be drilled every day, so that you say the line, then say to yourself Pause. Then we’ll find out what the pause is about.’ They took it in good part.”

Guys and Dolls (1982)

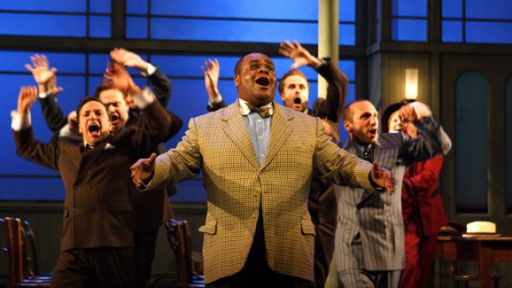

CLIVE ROWE as Nicely-Nicely in the musical Guys and Dolls in 50 Years on Stage. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

In 1982, Richard Eyre’s multi-award-winning Olivier Theatre revival of Frank Loesser, Abe Burrows and Jo Swerling’s “musical fable of Broadway” became the biggest hit of the National’s first 20 years. “I had to see [Guys and Dolls] to believe the raves,” Rex Reed informed readers of the New York Daily News.

“After all, the British do not suffer an embarrassed reputation for staging American musicals poorly without good cause… But this is the NT, where art is everything and only the most classical productions are mounted. They say there is nothing the actors in the NT can’t do, and now that I’ve seen… Guys and Dolls, I am prepared to believe it.”

Reed wondered what had overcome British theatergoers “notorious for their annoying reserve”, as he watched David Healy, as Nicely-Nicely Johnson, reprise “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ The Boat” seven times before audience cries of “More!” were finally silenced. In 50 Years on Stage, this song is performed by Clive Rowe, who first played Nicely-Nicely when Eyre revived his production at the National Theatre in 1996.

Pravda (1985)

RALPH FIENNES as Lambert Le Roux in Pravda in 50 Years on Stage. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

In the 50 Years on Stage segments from David Hare and Howard Brenton’s comedy about British newspapers, Pravda, Ralph Fiennes portrays amoral, rapacious South African media tycoon Lambert Le Roux. In Hare’s Olivier Theatre production in 1985, this ingenious tyrant was played by Anthony Hopkins, who, one day during rehearsals, had asked his director’s permission to “do Lambert as Hitler”, having played the Führer in a TV film. Hopkins stormed up and down, with ranting German intonation and some of Hitler’s gestures, one of which Brenton was thrilled to see retained on stage in the Olivier: “Whenever Le Roux fired someone, Tony kept one thing from that rehearsal: left hand gripping his right upper arm, then sticking his right thumb in the person’s face.” Hopkins gave Le Roux an eccentric posture: leaning forwards in repose and in motion, usually on tiptoes, his neck and back precisely angled to match the gait of an American TV producer whom Hopkins knew well. Le Roux’s lizard-like tongue – constantly darting in and out – was an exaggerated detail from Hopkins’ much-practised impersonation of Laurence Olivier.

Pravda won five awards, including Best New Play from the Evening Standard Drama Awards, and Outstanding Achievement for Hopkins at the Olivier Awards. For Hare, Pravda revealed “the full scale of [Hopkins’] theatrical genius. Deep in the run he would give performances beyond imagining. He could do anything at that point: the most beautiful acting machine you’ve ever seen.”

Angels in America Part One: Millennium Approaches (1992)

DOMINIC COOPER and ANDREW SCOTT in Angels in America in 50 Years on Stage. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

Dominic Cooper plays Louis Ironson and Andrew Scott plays his boyfriend, Prior Walter, in the Great Performances extract from Tony Kushner’s Millennium Approaches. On 8 February 1991, NT Director Richard Eyre had sat at home in west London, read Millennium Approaches, and, in his diary, described it as a “wonderful play… about the American Right, McCarthyism, Mormonism, Marxism, the Millennium, homosexuality, Aids, God and angels.” He wrote to Kushner, praising “quite the best piece of new American playwriting that I have read for ages – well, since Mamet.”

Millennium Approaches and Angels in America Part Two: Perestroika were eventually directed in the NT’s studio theatre, the Cottesloe, by Declan Donnellan, whose collaboration with Kushner on Part One was, to put it mildly, fraught. “Tony was the first living playwright I’d worked with,” Donnellan said, “and during the rehearsal period he seemed very likely to join the ranks of the dead.”

The playwright told me: “The director-playwright relationship is the most difficult in theatre, and not just because I’m a crazy person. Rehearsal periods are too short, [and there are] difficulties attendant on the playwright’s relinquishing of the material to the director.”

But, after watching its second preview in the Cottesloe, Kushner discovered that Millennium Approaches “had blossomed in a way that hadn’t seemed possible… I learned that directing is not sculpting. It’s about releasing energy, not imprisoning it.”

He credits Donnellan for doing “this very clever thing” with Angels in America, two plays which together contain more than 70, mostly quite short scenes: “At the very end of many scenes, Declan would find a place that worked textually and take the line from the beginning of the next scene and introduce it before the end of the previous scene”; a play that is “really bump, bump, bump [became] like a dance.” Donnellan attributes the “overwhelming” audience reaction to Angels in London (echoed in New York, where George C. Wolfe’s productions won a clutch of Tony awards) to “the effortless inventiveness of Tony Kushner’s imagination, and his sharpness and cleverness, which never upstages his humanity.”

A Little Night Music (1995)

DAME JUDI DENCH as Desirée Armfeldt, singing ‘Send in the Clowns’ in A Little Night Music. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

When Judi Dench sings “Send in the Clowns” in 50 Years on Stage, she is revisiting her award-winning performance as Désirée Armfeldt, from Sean Mathias’ Olivier Theatre revival of Sondheim’s musical. In 1995, Variety’s Matt Wolf praised Mathias and designer Stephen Brimson Lewis for giving A Little Night Music “an affective sweep as vast as the Olivier stage… [with] a minimal use of furniture and fabric that always leaves the show room to breathe, even as the occasional tableau (a lawn full of parasols, the magical lifting of a chandelier…) takes the breath away.”

“Send in the Clowns” helped Dench to earn an unprecedented double, taking the Olivier award for Best Actress in a Musical in the same year as the prize for Best Actress in a Play, which she won for playing a London drinking club hostess in Rodney Ackland’s Absolute Hell, also at the National.

The History Boys (2004)

(Left to right) DOMINIC COOPER, SACHA DHAWAN, JAMES CORDEN and PHILIP CORREIA in The History Boys by Alan Bennett in 50 Years on Stage. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

Since 1990, the National Theatre collaboration between playwright Alan Bennett and director Nicholas Hytner has been enormously successful, and The History Boys, in which an eccentric schoolteacher, Hector (Richard Griffiths in the original production; Bennett himself for 50 Years on Stage), helps the eight title characters to win places at Oxford or Cambridge universities, remains their biggest hit. However, when Hytner read a first draft of The History Boys in October 2003, a few months after taking over as NT Director, he was “dazzled by its wit and erudition, and by the urgency of its discussion of the purpose of education and the nature of historical truth”, but thought it might run for “only 70 or 80 performances” at the National, where his production would open the following spring. He had massively underestimated its appeal.

The History Boys National Theatre, West End and Broadway seasons, and several tours, took its total theatrical audience to around 800,000. When it claimed six Tonys in Play categories it equalled a haul established in 1949 by Death of Salesman.

War Horse (2007)

JACK HOLDEN as Albert in War Horse, with TOBY OLIÈ, THOMAS WILTON and MICHAEL BRETT as Joey, in 50 Years on Stage. Photo by Catherine Ashmore.

Still playing to packed houses in the West End, almost seven years after it opened in the NT’s Olivier auditorium, War Horse, adapted by Nick Stafford from Michael Morpurgo’s novel for children, is the tale of a country boy, Albert, separated from and reunited with his horse, Joey, during the First World War. The horses are designed by the Handspring Puppet Company, from Cape Town, and they are manipulated by puppeteers who are visible throughout the action. This technique, observes Hytner, means that the story is told “in a way that is completely fresh and unpredictable: the extraordinary puppetry, the extraordinary sense that a horse’s soul is being revealed to you on stage, through the kind of theatre alchemy that puts all its cards on the table.”

The 50 Years on Stage segment presents one of the show’s many indelible spectacles: the moment, from the end of Scene Three, when ‘at the top of his rearing up, young Joey makes way for grown Joey’; the smaller horse puppet vanishes and the full-sized horse puppet emerges from the upstage darkness.

Hytner, heading down from the fourth-floor NT Director’s office to his car on weekday evenings, sometimes sneaks into the back of the Olivier stalls to check on the audience for whatever was playing; once War Horse had opened in 2007, he started timing this detour to coincide with the collective gasp from 1,100 people at Joey’s Scene Three transformation.

London Road (2011)

In late 2006, Steve Wright, a forklift truck driver who lived in London Road, Ipswich, in eastern England, murdered five young women who were working as prostitutes in the area. In February 2008 he was imprisoned for life. This horrific case generated one of the most original productions the National Theatre has ever staged: the verbatim musical London Road.

Alecky Blythe’s interviews with residents of London Road, the Ipswich street where Wright had lived, and other people involved in the case, were set to music by composer Adam Cork and – as the Great Performances segment, featuring original cast members, vividly demonstrates – sung and spoken with all of the repetitions and hesitations of everyday discourse retained. Originally staged by Rufus Norris in the Cottesloe, London Road won the Critics’ Circle prize for Best Musical. Norris, who will take over from Hytner as National Theatre Director in April 2015, is soon to turn it into a feature film.

The Habit of Art (2009)

The National Theatre Story (2014) by Daniel Rosenthal covers 50 years of the theater's illustrious history.

Alan Bennett’s comedy, originally staged by Hytner in the Lyttelton, the National Theatre’s proscenium auditorium, sees a group of actors working in an National Theatre rehearsal room on “Caliban’s Day”, a play-within-a-play which dramatizes a meeting between W. H. Auden and Benjamin Britten at Christ Church college, Oxford, in 1972. With their director absent, the rehearsal is supervised by stage manager Kay (played in the original production, and in 50 Years on Stage, by Frances de la Tour), and her climactic speech provides the perfect Epilogue for the 50th anniversary gala, distilling the National’s history – and the range of work produced in its three auditoriums on the South Bank of the Thames – into a few lines, as Kay celebrates the NT’s commitment to “plays plump, plays paltry, plays preposterous, plays purgatorial, plays radiant, plays rotten – but plays persistent. Plays, plays, plays. The habit of art.”

Hytner could see why some people considered this speech “sentimental”, and yet, he told me: “I was always moved by it, because it felt to me like Alan, through Kay, writing pretty accurately about what it’s like to practise the habit of art [at the National]. ‘Plays persistent’ – that’s what it is, this place. Everybody here knows that, and everybody here works to that pattern; you go into every single play with the genuine expectation that it could be one of the exceptional ones, but the point is that it doesn’t matter if it’s not, because the persistent determination to put on stuff that’s worth doing and worth seeing outweighs the occasional disappointment.”

—-

The National Theatre Story (2014; 800 pages with illustrations) by Daniel Rosenthal is published in hardback by Oberon Books and distributed by Theatre Communications Group in the United States.