Premieres Friday, April 22 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/nowhearthis and the PBS Video app

Drawing from his Jewish roots, modernism and American folk music, Pulitzer-, Grammy- and Oscar-winning composer Aaron Copland created a distinctive American sound in both his classical compositions and film scores. Like Copland did for much of his career, host Scott Yoo and fellow musicians spend time working with students at a music festival in Colorado to strengthen their auditioning skills and better understand Copland’s music. To discover Copland’s inspiration, Yoo travels to New York to explore the Jewish music Copland was raised with as well as modernist music through performances by Cantor Daniel Mutlu, violinist Steven Copes, cellist Mark Kosower, festival music director and pianist Susan Grace and more. Later, Yoo becomes the student and learns from pianist and Copland enthusiast John Novacek about how the composer developed his signature sound, now so familiar to us all.

Places visited: Colorado Springs, Colorado; New York, New York

Follow celebrated violinist and conductor Scott Yoo as he travels the United States to uncover the musical influences of some of America’s most prominent composers — Amy Beach, Florence Price and Aaron Copland — in of the third season of Great Performances: Now Hear This. The documentary miniseries also spotlights two contemporary composers weaving the traditional music of their heritage into their compositions: Brazilian-born Sergio Assad and Indian American Reena Esmail. From coast to coast, the series shines a light on the immigrant experience as told through music, featuring local artists across musical genres including gospel, blues and more. Great Performances: Now Hear This Series 3 premieres Fridays, April 8-29 at 9 p.m. ET on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/nowhearthis and the PBS Video app as part of #PBSForTheArts.

Yoo is the Chief Conductor of the Mexico City Philharmonic, Music Director of Festival Mozaic, Conductor of the Colorado College Music Festival and the Founder of the Medellín Festicámara, a chamber music and social program in Colombia. He has conducted the London Symphony, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, L’Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra, Seoul Philharmonic, Dallas Symphony and San Francisco Symphony, among many others.

#PBSForTheArts is a multiplatform campaign that celebrates the arts in America. For more than 50 years, PBS has been the media destination for the arts, presenting dance, theater, opera, visual arts and concerts to Americans in every corner of the country. Previous Great Performances programs include Romeo & Juliet from the National Theatre, The Arts Interrupted, Coppelia, From Vienna: The New Year’s Celebration 2022, Reopening: The Broadway Revival and The Conductor premiering Friday, March 25 on PBS. The collection of #PBSForTheArts programs is available at pbs.org/artsand the PBS Video app. Curated conversation and digital shorts are also available on PBS social media platforms using #PBSForTheArts.

Throughout its nearly 50-year history on PBS, Great Performances has provided an unparalleled showcase of the best in all genres of the performing arts, serving as America’s most prestigious and enduring broadcaster of cultural programming. Showcasing a diverse range of artists from around the world, the series has earned 67 Emmy Awards and six Peabody Awards. The Great Performances website hosts exclusive videos, interviews, photos, full episodes and more. The series is produced by The WNET Group.

Great Performances is available for streaming concurrent with broadcast on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.organd the PBS Video App, available on iOS, Android, Roku streaming devices, Apple TV, Android TV, Amazon Fire TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. PBS station members can view many series, documentaries and specials via PBS Passport. For more information about PBS Passport, visit the PBS Passport FAQ website.

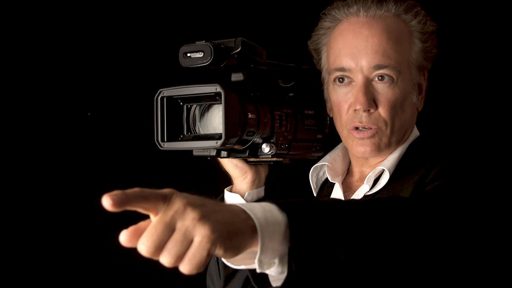

Great Performances: Now Hear This was created by producer, writer and director Harry Lynch and is a production of Arcos Film + Music. Harry Lynch, Scott Yoo and Richard Lim are executive producers. For Great Performances, Bill O’Donnell is series producer and David Horn is executive producer.

Series funding for Great Performances is made possible by The Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Arts Fund, the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, Jody and John Arnhold, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Thea Petschek Iervolino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, The Starr Foundation, the Seton J. Melvin, the Estate of Worthington Mayo-Smith, and Ellen and James S. Marcus. Funding for Now Hear This is also provided by The Iris and Joseph Pollock Fund, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, and the Jack Lawrence Charitable Trust.

Websites: http://pbs.org/nowhearthis, http://facebook.com/GreatPerformances, @GPerfPBS, http://youtube.com/greatperformancespbs, giphy.com/great-performances #NowHearThisOnPBS #PBSForTheArts