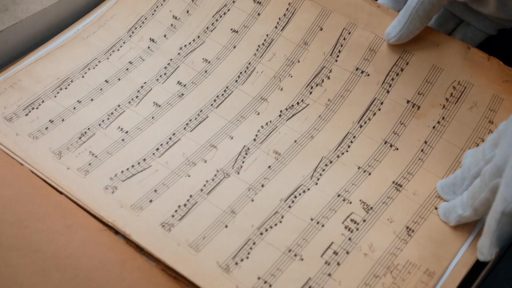

Host Scott Yoo follows the trail of great African American composer Florence Price, learning that West African music and European hymns inspired nearly all American popular music. He begins with the Arkansas archives that house Price’s work, which was originally found in the attic of an abandoned Chicago house. Then, Yoo joins pianist Karen Walwyn to discover where Price grew up and the spiritual music she was surrounded by in the South before moving to Chicago seeking equality and opportunity. Yoo explores Southern migrants’ musical impact on the city and gospel music with singer Vernon Oliver Price and former choir director Lou Della Evans Reid. Other performances by musicians inspired by Price, include pianist Michelle Cann, blues musician Jonn Primer, opera singers Rod Dixon and Alfreda Burke, showing how powerful Price’s influence remains today.

Places visited: Little Rock and Fayetteville, Arkansas; Chicago, Illinois

Follow celebrated violinist and conductor Scott Yoo as he travels the United States to uncover the musical influences of some of America’s most prominent composers — Amy Beach, Florence Price and Aaron Copland — in of the third season of Great Performances: Now Hear This. The documentary miniseries also spotlights two contemporary composers weaving the traditional music of their heritage into their compositions: Brazilian-born Sergio Assad and Indian American Reena Esmail. From coast to coast, the series shines a light on the immigrant experience as told through music, featuring local artists across musical genres including gospel, blues and more. Great Performances: Now Hear This Series 3 premieres Fridays, April 8-29 at 9 p.m. ET on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/nowhearthis and the PBS Video app as part of #PBSForTheArts.

Yoo is the Chief Conductor of the Mexico City Philharmonic, Music Director of Festival Mozaic, Conductor of the Colorado College Music Festival and the Founder of the Medellín Festicámara, a chamber music and social program in Colombia. He has conducted the London Symphony, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, L’Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Yomiuri Nippon Orchestra, Seoul Philharmonic, Dallas Symphony and San Francisco Symphony, among many others.

#PBSForTheArts is a multiplatform campaign that celebrates the arts in America. For more than 50 years, PBS has been the media destination for the arts, presenting dance, theater, opera, visual arts and concerts to Americans in every corner of the country. Previous Great Performances programs include Romeo & Juliet from the National Theatre, The Arts Interrupted, Coppelia, From Vienna: The New Year’s Celebration 2022, Reopening: The Broadway Revival and The Conductor premiering Friday, March 25 on PBS. The collection of #PBSForTheArts programs is available at pbs.org/arts and the PBS Video app. Curated conversation and digital shorts are also available on PBS social media platforms using #PBSForTheArts.

Great Performances is available for streaming concurrent with broadcast on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.organd the PBS Video App, available on iOS, Android, Roku streaming devices, Apple TV, Android TV, Amazon Fire TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. PBS station members can view many series, documentaries and specials via PBS Passport. For more information about PBS Passport, visit the PBS Passport FAQ website.

Great Performances: Now Hear This was created by producer, writer and director Harry Lynch and is a production of Arcos Film + Music. Harry Lynch, Scott Yoo and Richard Lim are executive producers. For Great Performances, Bill O’Donnell is series producer and David Horn is executive producer.

Series funding for Great Performances is made possible by The Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Arts Fund, the LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, Jody and John Arnhold, The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation, the Kate W. Cassidy Foundation, the Thea Petschek Iervolino Foundation, Rosalind P. Walter, The Starr Foundation, the Seton J. Melvin, the Estate of Worthington Mayo-Smith, and Ellen and James S. Marcus. Funding for Now Hear This is also provided by The Iris and Joseph Pollock Fund, Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III, and the Jack Lawrence Charitable Trust.