Premieres Friday, May 3 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/gperf and the PBS app

Places visited: California, Japan, New York City, Chicago

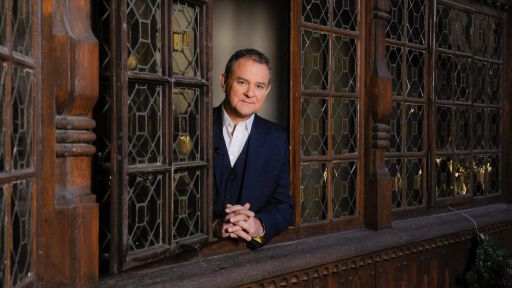

Follow host Scott Yoo’s journey to compose a piece of music for the first time. Seeking counsel from other composers, Yoo revisits his heritage in search of ideas, performs landmark pieces for inspiration and ultimately tests his work in progress.

♪♪ -Coming up on this strange episode of "Now Hear This," the composer we're following is Yoo[you], and by that, I mean me.

This all started with a request from an important festival patron.

You realize that I've never written anything ever.

This would be Opus 1.

As I figure out what to write... You could write a ballet, you could write a symphony, you could write a concerto for 16 bassoons.

...as I search for inspiration in different places and art forms... That's like the best piece ever.

-I come from British and Trinidadian background.

Almost every composition, there's always a little hint of calypso spice in there.

♪♪ -...as I turn to the experts for guidance... -Make music beautiful the way you hear it and feel it and make it yours.

-...then review my work in front of the festival board.

And then you realize "No, you're not brilliant.

You are a thief."

[ Laughter ] -My advice is just trust it and don't be reticent because I think music has to have its own inner life, right?

It has to go.

-This journey would give me and probably you a whole new appreciation for the difficulty of composing and the brilliance of great composers.

You know, it's what it is.

-I think it's really great.

-Up next on "Great Performances," the composer is Yoo.

♪♪ Major funding for "Great Performances" is provided by... ...and by contributions to your PBS station from viewers like you.

Thank you.

-I'd been commissioned to write this music by a festival patron, so I promised to present the work in progress to the board.

It would be the first public performance of anything I'd written.

And I have to admit, I was nervous.

I would see other people write music, and I thought, "Oh, I can do that.

It's not going to be that hard."

[ Laughter ] And so I sat down at the piano, sometimes 14 hours a day, to try to write something.

And I found it virtually impossible.

It was the hardest -- it is still the hardest thing I've ever tried to do.

This is the story of how it happened.

With no idea where to begin, I went to visit my friend, the pianist and composer, John Novacek.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ [ Both laugh ] -Crazy, I know.

-John, what possessed you to write that for the violin?

-All I can say is, I'm sorry.

[ Both laugh ] -But seriously, why do you write rags?

-Ragtime really was my entry point into music.

Beethoven and Bach came a little bit later.

-Really?

No kidding?

-Yeah.

I was lucky to grow up during the 1970s, and there was a great ragtime revival going on.

"The Sting" actually made Joplin's "Entertainer" a top-40 hit, 70 years after it was written.

This music, to me, was the most beautiful stuff I've ever heard, so I knew I wanted to play rags.

Then later on, when I was in my teens, I started writing them too.

-The reason I ask is because this friend of mine, she's commissioned me to write this piece.

-Mm-hmm.

-It's almost impossible to know what medium to work in.

You could write a ballet, you could write a symphony, you could write a concerto for 16 bassoons.

Where do you start?

-If it were me, I would start with something that I'm very comfortable with.

We're talking about ragtime.

That's not the only kind of style I compose in, but it's something that comes naturally to me.

What is the kind of medium you like to play?

-I love whatever I'm playing at the moment.

With piano is good, because it's just such a versatile instrument.

-Well, I think it's great to start in a chamber format.

That gives you something to work with on a slightly smaller scale.

Good luck.

[ Both laugh ] -Alright then, a chamber piece with piano.

I love piano quartets, so I decided that would be the format.

Then I programmed a festival with a few of the greatest ones so I could be inspired by the best.

At this rehearsal, I had Stewart Goodyear, Ani Aznavoorian, and Maurycy Banaszek.

♪♪ Nice.

Bravo.

-First ever piano quartet.

I can't believe that.

-You mean, period?

-Period.

-I've been doing a deep dive into this because I'm maybe going to write a piano quartet myself.

-What?

No, amazing.

-It was surprising to me that the piano trio, the predecessor, really is kind of a baroque form.

Then Mozart said, "I'm going to add the viola."

-Well, he did love the viola.

He actually did play it himself pretty well, too.

-He wrote a lot of good pieces for viola.

-Oh, yes.

-Are you thinking about your approach to the piano quartet?

-What I'm worried about, quite frankly, is that I'm going to write a piano trio and then add a second violin.

-Got it.

-You know what I'd love to do?

I'm wondering if Ani and Stewart and I can play it without you?

-Please.

-Because I'm curious to know how much of a difference it really makes.

Yeah?

-Which section is this?

-23.

-Okay.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Yeah, very different.

-If you didn't know the viola part from previous listenings, you'd think that was perfectly lovely.

-Yeah.

It almost sounds like a piano trio, right?

Maybe not the best piano trio, but a good piano trio.

-Solid one.

-Can we add Maurycy?

Maybe play extra loud or something?

-[ Laughs ] ♪♪ ♪♪ -Such a strange solo, isn't it?

Because you have almost nothing to play, but you're the most important.

-F to G-flat and back.

That's it.

-So simple.

-But it makes it way better.

He's delivering something meaningful from the middle.

Right?

That's what the piano quartet adds.

It adds that tenor voice.

-Yeah.

-Can we try it again?

-Beginning?

-Yeah.

-Okay.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -Stewart is also a pianist composer, so I went to meet him backstage to get more advice.

If I could find him... Stewart, are you in there?

Is essentially the composing part of your brain always on?

-It's always on.

Sometimes it never leaves me alone.

Even at nighttime, maybe around 2 in the morning, if there's an idea that just comes up like a light bulb, I have to write it down, otherwise I forget.

-Where do the ideas come from?

-They just come from somewhere within me.

I come from a British and Trinidadian background.

From that background, a lot of music became a part of my childhood soundtrack.

-Did you visit Trinidad a lot when you were a kid?

-Every summer.

It was like my summer home.

I would visit my cousins, and calypso was everywhere.

-Really?

-It became a part of my system and a part of my fabric.

In almost every composition, there's always a little hint of calypso spice in there.

-So when you go to Trinidad, your ears are open?

-My ears are open.

-You want to play some for me?

-I'd love that.

Let's go to the piano.

-Okay.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Wow.

That's really impressive, Stewart.

Show me the calypso in it.

-Every time I heard a calypso melody, they always had these chords... [ Notes play ] Or... ♪♪ I just incorporated that into my own calypso melody, so what you got was... ♪♪ -I'm glad to hear you say that because it almost sounded like I heard it before, even though clearly I didn't.

-That was the purpose.

-That's great.

-That was on purpose.

-That's terrific.

-Then with the percussion section, when you hear the maracas or the cow bell... [ Vocalizing ] That's what you have.

[ Notes playing ] And the bass drum... [ Vocalizing ] ♪♪ The pianism equivalent would be... ♪♪ -So the energy of calypso goes through your brain and then gets recomposed and turns into that.

-Right.

-Very cool.

Very cool.

-So what are you going to write?

-Unfortunately, I don't have the calypso background or the mazurka background.

-What's your background?

-Well, I'm from Connecticut.

-Beautiful.

[ Both laugh ] Well, what other background?

What else is in your fabric?

-Well, my father was Korean, and my mother is Japanese.

-If you had to choose a country, if you're out of your comfort zone and you wanted to explore something very, very deep within yourself, which country would you go to?

-Probably Japan.

Rather than fly halfway around the world, I went to New York's Japan Society to see how I might incorporate Japanese influences with curator Tiffany Lambert and koto player and composer Yumi Kurosawa.

-These are screen prints and oil paintings by Kyohei Inukai.

He is a really wonderful example of an artist who really melds Japanese and American aesthetics.

-I was reading outside that his name was at one point Earle Goodenow.

-Yes, that's astute.

He was born Earle Goodenow.

It's actually his mother's name, Lucene Goodenow.

She was an artist.

His father was a Japanese immigrant, and his name was Kyohei Inukai.

-So he took his father's name?

-He did.

In 1954, after his father passed away, he went to Japan for the first time and on that trip decided from that point forward, he was going to become Kyohei Inukai.

As you can see, he signs his artworks with that name.

-After he changed his name, did his work suddenly become very Japanese?

-There is some more work of his that starts to incorporate more traditional Japanese aesthetics and practices.

-Tiffany, are these all Inukai pieces?

-They are.

Quite poignant in that, it's some of the last works that he ever created.

They're rendered on Japanese washi paper, handmade paper.

What he's really doing with this body of work later in his career is taking traditional Japanese artistic practices and employing them in an abstract expressionist style, or a very Western style.

-Obviously, I have a lot to learn from you, Tiffany, but I also have a lot to learn from you, Yumi.

You're from Japan.

-Yes.

As creators, we do try to get closer or combine other cultures, which is, I think, great.

-I know you brought your koto.

-Yes.

-Can we check it out?

-Of course.

-Okay, let's go.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ That really sounds like Japan.

-Yes, because of the scale.

One of the most important players and composers in koto history, Kengyo Yatsuhashi, invented Hirajoshi tuning, which is this one.

[ Notes play ] -Hold on.

Do that a little slower.

-Yeah.

♪♪ ♪♪ -Okay.

So that is... ♪♪ -Yes.

You got it.

-How many strings is this?

-This is 13 strings.

And this is actually 21-string koto.

-Wow.

-I want to show you some scales on the koto.

This is diatonic scale.

Let's see, C major.

And if I want to change to D major, either I bend strings... ♪♪ ...or move bridges.

♪♪ Same thing.

-So you're bending the pitch by pulling the string?

-Yeah.

-This does not feel like gut.

This feels like some kind of a synthetic.

-Yeah, this is a nylon string.

-They weren't always made out of nylon.

-No.

Used to be silk, but it's way too delicate, especially for contemporary music.

-Speaking of modern, you sent me your piece for violin and koto.

-Mm-hmm.

-You want to give that a try?

I've been practicing.

-Yeah, sure.

-Yeah?

-I'm so honored.

-Let's do it.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ As I started working on ideas, I went to Sue Cahill for advice.

She's a professor, bassist, pianist, and composer who's brought Japanese influences into her own work.

Sue, Yumi taught me the koto scale, just the open strings.

It's beautiful.

But when you try to play that on the violin with a bow, it still sounds like a koto, and so I dug up a whole bunch of Japanese scales.

Like this one, for example.

[ Notes play ] Everything started to sound like... [ Notes play ] I mean, it just really sounds...

It sounds like a cliché.

-Yeah.

-That's not what I'm trying to do here.

I'm trying to make some kind of a piece that has a little bit of the tradition in it, but it's not hitting you over the head.

-Yeah, "Madame Butterfly."

-Yeah.

-Well, first of all, I never start at the beginning.

[ Piano notes play ] Right?

So instead, I'll start somewhere in the middle... [ Notes play ] ...and maybe do some different rhythms.

Some bigger intervals, too, because these intervallically are pretty close.

They're thirds and they're half steps.

So if I make the intervals bigger... [ Notes play ] ...then all of a sudden it still has the effect of the scale, but it doesn't sound as cliché.

I think just having that little limitation, whether it's a scale or if it's a rhythm, very helpful.

You remember that Satoh piece I sent you a while back?

-Mm-hmm.

-That piece is a great example of something that is written in a traditional Japanese style.

It uses one of these scales, but it sounds very modern and very minimalistic.

I think that might be a good thing for us to go through.

-Yeah, let's read it.

-Yeah.

♪♪ -It was becoming clear.

To really be inspired by Japan, I'd have to go there.

♪♪ ♪♪ I started at Sankeien Garden in Yokohama, with ikebana artist Mika Otani.

-Now is cherry blossom season, maybe the most beautiful season.

♪♪ -How long do these cherry blossoms last?

-They last two weeks.

-It wouldn't be special if it lasted all year round, right?

-Yes.

♪♪ Please look at this scar.

We really feel this kind of a scar is also really beautiful.

Because in Japanese culture, we love imperfection.

We think imperfection is more perfect than perfection.

All living creatures are imperfection.

That's why we are so beautiful.

♪♪ Please look at this branch.

Each branch is stretching out to the lake.

This kind of unbalanced shape, it's more natural, and it's more free.

And here, we have so many spaces.

That's why we can realize each line's beauty.

-So the space that the branches form is almost as important as the branches itself.

-Yes, yes!

People think the space is something to fill up.

But we think space is something to create.

♪♪ We call the space ma.

And ma is maybe the most important common element in all Japanese culture.

The minimum use of materials is much more expressive than the use of many.

-Hmm.

-If we have a lot of cranes, we cannot appreciate each crane.

But with a lot of ma, we can realize the expression on the face of the crane.

The shape of the bird's wings.

All the details.

♪♪ -Mika has been practicing ikebana for almost 30 years.

She's a true master.

♪♪ -We talk with flowers.

Just me and the flower.

And I asked him, "What do you want to do?"

And he says, "I want to flow, like this."

♪♪ The ikebana is half improvisation, picking up the beautiful aspect of nature and adding our emotions and ideas.

-Wow.

♪♪ ♪♪ Now, improvising on the violin is not something that I do.

Improvising on the violin is when the yellow light is going on, and there's something that has very badly gone wrong in a concert, and I'm trying to figure out "where am I?"

♪♪ I was watching this unbelievable woman do a beautiful sculpture with branches.

And I sat back, and I started to play... ♪♪ ...and I thought, "This is really good."

♪♪ Then a couple of weeks later, I looked down at what I wrote, and I realized that I had written out the recapitulation of Honegger's 2nd Symphony, 2nd Movement.

[ Laughter ] And you know, it's really crushing when you think that, "Oh, I'm so brilliant," and then you realize, "No, you're not brilliant.

You are a thief."

[ Laughter ] This was obviously a problem.

So I went to seek counsel from the master, Bernard Rands.

Few are more respected in modern music.

Which piece are you working on these days?

-This is a piece for solo cello.

It's called "Memo Nine," and it's for Alexander Hersh.

In the beginning of a brand-new piece, there are many possibilities and so many options that one has to, I think, narrow down to something quite specific.

So by using this notation system: A, La, E, 10 is H in the German.

So it's Alex Hersh.

-No kidding.

-He doesn't know that yet.

[ Laughs ] But rather than have writer's block, it's better to start with something.

-Well, that kind of brings me to why I'm here.

I'm writing a piano quartet, and I started improvising, and I realized that I was playing part of Honegger's 2nd Symphony.

Now whenever I put something down, I'm wondering, "Is this my writing, or is this somebody else's writing?"

-I think you're being a little bit neurotic.

First of all, the fact that you are the violinist that you are, and the conductor that you are, use the facilities that you have as a fantastic musician to isolate a particular musical idea.

On the one hand, one wants to be part of this huge, huge inheritance that we have of wonderful music from so many periods.

At the same time, you can limit that by, in my case for example, I do not use any other composer's score as a model.

I'm surrounded by fantastic literature, poetry, architecture, you name it.

All of these feed into a creative imagination.

Make music beautiful the way you hear it, and feel it and make it yours.

♪♪ To you, I do recommend carry a very simple notebook.

I think in that way, you'll be working on your own ideas, not on somebody else's.

♪♪ ♪♪ -In Kamakura, at the Engaku-ji Zen temple, I went to see a monk, Jotuku Fukuda.

♪♪ ♪♪ -This is national treasure.

Shariden.

We call it shariden.

This is the oldest building of typical Zen structure.

-The oldest typical Zen structure.

-Yes, in Japan.

That is the reason why this is national treasure.

[ Birds calling, frog croaking ] -It's so quiet here.

-Yeah, very quiet.

-You can hear a frog and some birds.

That's about it.

-Yeah.

Everything you can hear.

-I feel like every time I speak, I'm interrupting the silence.

-Yeah.

-This is a good place to study meditation and Zen in the world.

-Yes.

That's right.

Yeah, yeah, yes.

There is a monk training center here.

-You're going to teach me a little bit?

-Yes, of course.

-Okay.

-Yeah, that's right.

Please sit down, sit down.

First important thing is straighten up your backbone, the bottom of your backbone.

Yes.

Okay.

The second important thing is concentrating on the two inches below your belly hole.

This is the center of your body and the center of your mind.

Please touch your thumbs and make egg round form here.

And the last very important thing is the breath.

Breathe in the whole air to the bottom of your lungs, very slowly.

Breathe out the whole air through the nose, slowly.

Then is repeating this simple breath.

There is no room to think about anything.

Nothing.

Totally nothing.

-But I couldn't think about nothing.

-In Japanese Zen, we have a custom of hitting bar.

This bar.

We call it keisaku.

When you feel you cannot concentrate on your breathe in, breathe out, breathe in, breathe out, please make gassho.

♪♪ [ Flesh slapping ] ♪♪ -I still couldn't stop Fauré's piano quartet from going around in my head.

I had to find some way to make that music my own.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Back in California, I was rehearsing again with Stewart, Jonah Kim and Caitlin Lynch.

♪♪ Oh, boy.

That's like the best piece ever.

-So good.

-You got to steal from the best, right?

I actually took the cello solo, and I deconstructed it because I just thought, "Wow, how did he write that?"

It's so good, but it's like sleight of hand or something.

How is he coming up with those changes?

So I kind of internalized those changes, and I tried to apply them to my own music.

Not exactly copy them, but try to use that as inspiration.

I wrote this little moderato movement, this slow movement.

Can we just try that one?

-Sure.

-Okay.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Hearing it next to Fauré, it was clear it needed some work.

So I went to see another famous composer, in Chicago, Augusta Read Thomas.

What I was trying to do with this movement was essentially homage to Fauré, but using Japanese scales.

And as you can see, once I got the harmony down and the basic tune, it was like an airplane but it just never took off.

-I loved getting to know this piece, because I want to feel like, what would you make?

-Yeah.

-But I do have some thoughts for you.

When you're talking about the French, the Fauré perfumes of the piece, and then the Japanese modes, one of the things that's interesting is, where are those layer cakes coming together?

What happens at those moments where you intersect?

If it always shifts at the same rate... -It's always shifting at the same rate.

-Then it's just blue, red, blue, red, blue.

But if you go, blue, red, yellow, blue, red, purple, blue, red, whatever, I'm just totally making this up, then all of a sudden, the underlying harmony, which is coming from the Japanese influence on the Fauré, comes to life, like wow!

I feel like this is absolutely fabulous, where you actually start to build up and you have this crescendo and you go here, and it's this beautiful modulation.

-Yeah.

-I wouldn't change that at all.

-Okay.

-But you're building this thing up, and the whole thing is going, and then what do you do?

You just go, bop, bop, bee, bop.

-Right.

-You could make that into 20 bars.

It's in the sound.

-It's amazing how insightful you are because you picked up on this feeling that I have of...fear.

It's fear.

It's almost like a self-protection thing.

It's like, "Well, okay, this is a good moment, but people might not like it, so just get off it and go somewhere else."

-My advice is to allow the music to go where it needs to go.

-Right.

-There's so many great things about this, and it's incredibly musical and graceful and interesting, with rich kinds of harmonic world.

You've got all of this in there, and then I feel like you're holding yourself back.

So I would say just trust it and don't be reticent because I think music has to have its own inner life.

Right?

It has to go.

And if we're reticent, we're stopping the thing that's going.

So I would say you have to jump in.

-And so I rewrote it.

I threw away most of the material, rewrote it, and I hope you like the new version.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ My next stop in Japan was to visit the Aikido class of the revered master Ryuji Shirakawa.

[ Wooden swords clacking ] -They are doing weapon techniques, and this is because the roots of Aikido goes back to the samurai era, when the samurais wore a sword during their day.

Generally, Aikido, we usually practice body-against-body techniques, but all the movements are basically based on how, in the past, samurai used the sword.

-He makes it look easy.

It's so fluid.

It's like ballet when he does it.

-Yeah, it's really beautiful.

So, Sensei is going to show empty-handed techniques, freestyle.

-Okay.

Without weapons?

-Without weapons.

-Okay.

-In Aikido, the purpose is not to defeat the opponent.

We throw each other, the opponent and the defender, because by being thrown, we actually learn how to throw.

-I've never heard of a fight where the point is not to defeat your opponent.

-Yes.

The focus is on the self-development.

-Wow.

[ Mat thumping ] [ Clapping ] So what was happening there?

-[ Speaking indistinctly ] -When you're grabbed, if you do like this, you get tense, and your force will collide with the opponent's force.

-Okay.

-[ Speaking Japanese ] -So you have to be relaxed, and raise the elbow.

-Raise the elbow, okay.

-[ Speaking Japanese ] -Then just change the direction.

-So somebody attacks very strongly, but he gently redirects the force.

-Exactly.

Why don't you try?

Please grab Sensei.

Attack him.

-[ Chuckles ] Really?

-Yes.

Just grab his hands as strong as you can.

-Okay.

[ Laughs ] But he was actually -- I could feel that his arms were completely relaxed.

-[ Speaking Japanese ] -I'll try one more time.

-Yes, please.

-[ Laughing ] The sensei is being very gentle, but what's interesting is I can feel that my -- it's like a boomerang.

My own force is...

I'm pushing myself down to the ground.

But that's the point, right?

-Exactly.

-That you can get power from being relaxed.

-Exactly.

-That's not what we're taught, in America anyway.

Everything is force, force, force.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Okay, I know we all have to go to our next rehearsal, but I sent you those PDFs of that scherzo that I wrote.

-Yep.

-Yeah.

-Can you guys get that out?

Alright, so a couple of caveats.

This is a maiden voyage, so you got to be patient.

We went to Japan, and we saw Aikido, and it's a crazy martial art where your job is to protect your attacker, which I think is a beautiful sentiment.

And you use their momentum, you deflect their momentum.

You don't punch back, you just deflect.

So let's give it a try.

We're going to get lost.

This is not that easy.

But if you don't mind playing it, that would be really a big favor.

♪♪ ♪♪ I tried to show the attack with as much dissonance as possible.

Then all of that dissonance gets just shifted one half step in either direction to make a major chord or a minor chord.

♪♪ ♪♪ When the person gets pinned, they yell uncle.

You'll hear "bup, bup," and that means they get let up off the floor.

[ Mat thumps ] ♪♪ Then there were like 50 people throwing each other to the ground, and I started hearing a Viennese waltz, because it just was so absurd.

It looked like the world's most messed-up waltz.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ Well, I mean, you know, it's what it is.

-I think it's really great.

-How are the parts?

Are they unplayable?

Do I need to rewrite anything?

-No, they're comfortable.

Obviously, you know how to write for strings.

-Well, the viola part is really high.

-As long as you do it on the A string is the first thing.

Because that's not fair if you have your E string.

Yeah, yeah.

♪♪ Yeah, you got it.

-At the end of my trip in Japan, I went to teamLab in Tokyo, and I had this really otherworldly, immersive art experience.

It was the greatest gold mine of ideas for my piece.

Takashi, one of the partners in teamLab, gave me a personal tour.

♪♪ You walk down this dark corridor, and suddenly it feels like the place has been flooded.

I love this.

♪♪ ♪♪ You go into another room, you're shin deep in water, and there are koi that are projected onto the lake.

But when you go to touch them, they explode into flowers.

That's beautiful.

I love that.

♪♪ ♪♪ It's moving!

-Yes.

-You almost feel like you're flying or something like that, or you're in the clouds or something.

That's incredible.

It's a difficult question, "What is art?"

-Yes.

♪♪ -And what about art?

Great design is like an answer.

Great art is like a question.

-Yeah.

♪♪ -Whoa!

They had this hallway of mirrors with crystals hanging down.

I don't even know how to describe it.

Oh, wow!

I really felt like I was almost walking around in my own brain.

And it was so uncomfortable and liberating at the same time.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ If you ever decide to compose or create anything, here's what I learned.

Write what you love.

Seek inspiration in meaningful places.

Innovate within tradition.

Create space, let things breathe.

Don't hold back, let things go, to find their own shape.

Rewrite and rewrite again.

♪♪ ♪♪ All that work, and I'd only begun my piece.

Luckily, I have till the next festival to present the finished work.

For now, I've gained an even greater appreciation for composers.

Anyone who can create new music has my deepest respect.

I'm Scott Yoo, and I hope you can now hear this.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -To order "Now Hear This" on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

This program is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

To find out more, visit pbs.org/greatperformances, find us on Facebook, and follow us on X.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪