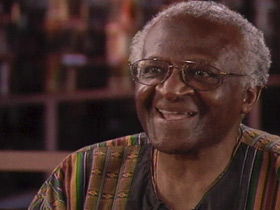

South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu

BOB ABERNETHY: It’s never easy for a church to admit having been wrong, especially about its interpretation of the Bible. But this week, that happened dramatically in South Africa. For generations, under South Africa’s old system of official racial segregation, the Dutch Reform Church provided apartheid’s religious and theological foundation. Its leaders argued that the Bible itself ordained white rule. But this past week at its national meeting held every four years, the Dutch Reform Church adopted a resolution calling apartheid not only wrong, but sinful and a travesty of the gospel.

Among those praising the Dutch Reform condemnation of apartheid was South Africa’s retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his nonviolent opposition to apartheid. He remains South Africa’s premier symbol of moral authority. After South Africa’s multiracial elections and change of government in 1994, at the personal request of President Mandela, Tutu chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the official body that brought to light the atrocities of apartheid on both sides, hoping truth would heal bitterness.

This year, Tutu is a visiting professor at Emory University in Atlanta. I asked him about a recent poll reporting that the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had made South Africa’s race relations worse.

Archbishop DESMOND TUTU (South Africa): Anyone who expected that the revelations that have come as a result of the work of the commission would make people suddenly embrace each other and love each other was totally unrealistic. I mean, when you’re a mother, you hear that your child was abducted and they shot him in the head and they burned his body, and as they were burning his body, they were having a barbecue on the side. If that mother were to say, “I love the people who did this,” she would be crazy. People would say she was abnormal.

ABERNETHY: How long do you think it will take before there can be reconciliation in South Africa?

Archbishop TUTU: It is already happening. I don’t think that you will ultimately say we won’t ever need to have people trying to be reconciled, but most of the people will be reconciled in maybe 10 years. It could be shorter.

ABERNETHY: And the greatest lesson from the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission?

Archbishop TUTU: I learned that we have the capacity for the greatest possible evil, all of us. But more exhilarating, we have the capacity for the greatest possible good. Human beings are an incredible creation.

ABERNETHY: With the U.S. Congress beginning hearings on whether to impeach the president, I asked Archbishop Tutu what his experience with confession and forgiveness in South Africa might say to this country.

Archbishop TUTU: It is never easy to say, “I am sorry.” Those are some of the most difficult words in any language. And when someone has said them, then those of us who are believers ought to be ready to move forward to embrace them with the words of forgiveness. We need to err on the side of generosity or spirit, because confession, especially in the open, publicly, is a desperately, desperately difficult thing. It’s difficult for a husband and wife in the intimacy of their bedroom. You can imagine when it has to happen in the full glare of television lights.

I myself can’t see how much more we want from that person, because he stands, in a sense, naked, if you will forgive the expression, no longer seeking to justify. And for us, especially us who are Christians, once a person is at that point, the gospel constrains you to forgive.

ABERNETHY: Tutu acknowledges that the constitutional and legal processes must proceed. Still, he thinks some Americans have been too judgmental.

Archbishop TUTU: We are forever exalting sexual sinfulness over other kinds of sinfulness. Whether you — when you look at how Jesus operated, the people with whom he was most harsh were not those who fell, according to us, through the flesh. He was far more hostile to people who were proud, people who were forsaken, hypocritical. He was — he was harsh on them. Gentle with the woman caught in adultery, gentle with a Mary Magdalene, who is a prostitute, not so gentle with the Pharisees who thought they knew. And we need to work out for ourselves whether we ourselves are not being like those whom Jesus condemned.

ABERNETHY: Last year, the enthusiastic archbishop was diagnosed with cancer and treated for it. But now, characteristically, he says he feels wonderful.

Archbishop TUTU: I think it’s a good thing to have had cancer, because it’s a wonderful indication of your mortality. And it actually makes you become more grateful, more appreciative of things that you used to take for granted. I now realize, I mean, when I attend a funeral, and I see the coffin descend into the grave, that, hey, sometime, it’s going to be me.

And, as I say, it does give a new intensity to your living. It gives a new quality to relationships. You look at the rose with dew on its petals, and there’s a new intensity to its beauty because you say, “I may not be seeing this for a very, very long time.”

ABERNETHY: How many people do you know who could say cheerfully it’s a good thing to have had cancer? Archbishop Tutu will present the official findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to South Africa’s President Mandela on October 28th.

One of the rules of the TRC was that no one coming forward to acknowledge crimes had to apologize. Archbishop Tutu clearly respects the importance of confession and repentance, but he explained in our interview that in South Africa, they did not require anyone to say, “I’m sorry,” because they felt they could never be sure the person saying the words was really contrite.