In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The Legacy of C.S. Lewis

BOB ABERNETHY: November 29 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of the late C. S. Lewis, one of the most influential and beloved Christian writers in this century. Lewis, who was British, wrote 38 books, from the best-selling children’s book The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe to Mere Christianity, one of the most widely read explanations of the Christian faith. Our critic, Martha Bayles, recently traveled to England to examine Lewis’s legacy.

MARTHA BAYLES: I am one of 800 Americans who have come to Oxford, England to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the birth of its famous former resident, the writer C. S. Lewis.

Unidentified Man #1: Well, I flew all the way from Honolulu to be here in England, and the reason is because when I became a Christian at the age of 15, never having gone to church before then, C. S. Lewis became my early mentor, and reading so many of his books really was a foundation of my Christian faith.

BAYLES: Lewis is renowned for his children’s stories, The Chronicles of Narnia, and for his literary scholarship done here at Oxford’s venerable Magdalen College. But those works are eclipsed by his Christian apologetics, a series of short books that are eloquent, lucid, emotionally honest, and hugely influential.

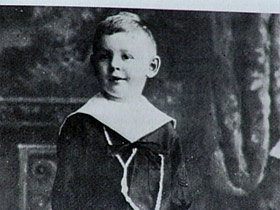

Born a Protestant in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Lewis rejected the religion of his boyhood, which he later called “the dry husks of Christianity,” for its hatred of Catholicism. A brilliant student, he was wounded in World War I and returned to Oxford an agnostic.

Born a Protestant in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Lewis rejected the religion of his boyhood, which he later called “the dry husks of Christianity,” for its hatred of Catholicism. A brilliant student, he was wounded in World War I and returned to Oxford an agnostic.

C. S. Lewis loved a good argument, and he had a lot of them. One of the most famous took place here on Addison’s Walk at Magdalen College. It was after that argument that Lewis became a believing Christian.

Lewis began the evening talking about myth with two friends, one of them J.R.R. Tolkien, author of Lord of the Rings. They argued for hours about whether some myths were true. And back in his room at 3 a.m., Lewis wrote to another friend, “I have just passed from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ.” He joined the Church of England and for years attended services here at Holy Trinity in the village of Headington Quarry. But Lewis did not just write for his fellow Anglicans; his message crossed national and denominational borders.

Thomas Howard, professor of English at St. John’s College in Massachusetts, explains Lewis’s American appeal.

Thomas Howard, professor of English at St. John’s College in Massachusetts, explains Lewis’s American appeal.

Professor THOMAS HOWARD (St. John’s College, Massachusetts): Yes, I think it started with Lewis’s book Mere Christianity, in the earlyish-to-middish forties, and the evangelicals who had been typecast by Hollywood, the stage, novelists, everybody else as sort of Appalachian ignoramuses found an articulate, incandescent intellect.

BAYLES: A key destination for Americans is Lewis’s home, called The Kilns because it was originally a brick works. Stanley Mattson is the director of the C. S. Lewis Foundation, which organized this festival and has run a tremendous volunteer effort to restore The Kilns.

Mr. STANLEY MATTSON (Director, C. S. Lewis Foundation): This was a home that was, literally, choking with weed grass. The windows—we found vines coming through the windows at six, eight feet into this very room, and it was very sad to see it.

Mr. STANLEY MATTSON (Director, C. S. Lewis Foundation): This was a home that was, literally, choking with weed grass. The windows—we found vines coming through the windows at six, eight feet into this very room, and it was very sad to see it.

BAYLES: George Sayer, a student and close friend who has written a Lewis biography, is not sure Lewis would approve.

Mr. GEORGE SAYER (Friend of C.S. Lewis): He’d have been embarrassed and thought quite incorrect the interest in the personality of the man.

BAYLES: Douglas Gresham is the son of Joy Gresham, an American who married Lewis in 1957 and died three years later. Their story was made into a film called “Shadowlands.” Douglas recalls how his stepfather felt about fame.

Mr. DOUGLAS GRESHAM (Stepson of C.S. Lewis): I can remember he and my mother used to tease each other about it occasionally at the dinner table, for example, when he would receive some letter from—a letter of adulation from a fan, and he would read it out at the table with a great grin on his face, and my mother would chide him gently.

Mr. DOUGLAS GRESHAM (Stepson of C.S. Lewis): I can remember he and my mother used to tease each other about it occasionally at the dinner table, for example, when he would receive some letter from—a letter of adulation from a fan, and he would read it out at the table with a great grin on his face, and my mother would chide him gently.

BAYLES: Does this mean we should ignore the trappings and details of Lewis’s life?

Mr. MATTSON: When we fail to honor people and one another, we really, I think, become impoverished as a people, so I think remembering is very important business.

BAYLES: Christianity for Lewis was not a feel-good religion. Yes, he says, we should love other people, but that’s not the end of the story.

Gilbert Meilaender teaches Christian ethics at Valparaiso University.

Professor GILBERT MEILAENDER (Valparaiso University): Lewis has an extremely strong sense of the importance of close ties in life, how it’s impossible to live fully without them, but how much pain they bring and particularly how much pain they bring when one is drawn away from them toward God.

Unidentified Man #2: C. S. Lewis dealt with pain and struggled with pain, and my motivation in coming is to try and make sense of life and pain.

Unidentified Woman: And I think that we’re here to use him in a sense as an icon—in the true sense of the word “icon” in that you look through the image to something further, which is God.

BAYLES: I’m Martha Bayles for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly in Oxford, England.

Choir sings hymn.