Passover Preparations

BOB ABERNETHY: On our calendar this week, the Jewish festival of Passover, the eight-day commemoration of the exodus from Egypt. On Wednesday evening, Jews will gather for a Seder, Hebrew for “order,” to retell the story of the ancient Israelites’ deliverance from slavery. Many of us know about the Seder, but few know about the extensive preparations for Passover, preparations which are supposed to cleanse the home and the spirit. Here is contributing correspondent Arthur Magida.

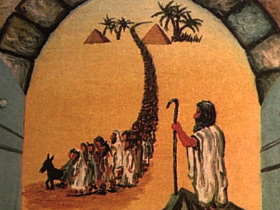

ARTHUR MAGIDA: Passover is the story of an enslaved people who were freed of a pharaoh or leader who refused to let these people of another god go. But Passover is more than the story of freedom; it is also the story of how the god of the Jews made that divine presence felt in history — a presence, explains Rabbi Sabath of CLAL, the Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, that sustained and enriched the Hebrew people.

Rabbi RACHEL SABATH (CLAL, New York): It’s the master narrative, I think, not just of the Jewish people, although originally of the Jewish people. It’s the master narrative, meaning the story of what it means to be a free human being for every people.

I think more than any other holiday, more than anything else in Jewish tradition, Passover teaches our core values.

MAGIDA: In the United States, this is the most observed of all Jewish holidays. About 90 percent of American Jews attend a Seder, the dinner on the first two nights of Passover at which the exodus story is retold.

Rabbi SABATH: It’s the most American of Jewish holidays because of the values of freedom and freedom of religion and freedom of expression. Certainly it’s the parallel to Thanksgiving. The narrative of Passover plays itself out in every period of human history, in every period of human history and in every society.

MAGIDA: Today, just as with the Israelites who were fleeing from Egypt, Jews have to prepare for the freedom which the holiday represents. Because the Hebrews didn’t have time to bake bread, matzoh, a thin, unleavened bread, has become the ultimate symbol of Passover. Rabbi Harlan Wechsler in New York explains why.

Rabbi HARLAN WECHSLER (Congregation Or Zaurua, New York): When our ancestors came out of Egypt, they were so quick once they realized that they finally had the opportunity to be redeemed su — from slavery that they didn’t tarry and that they didn’t allow their bread to rise. Their bread didn’t rise and therefore, they ate unleavened bread. And therefore, we eat unleavened bread. This enables us to participate as modern people in a very ancient tale.

MAGIDA: To this day, matzoh is made in no more than 18 minutes from the moment the dough is mixed, to preserve the tradition that was set when the Hebrews swiftly fled Egypt.

Rabbi WECHSLER: Just think of how beautifully personal this is, that they’re not just baking matzoh, they’re doing it for the sake of the observance of the commandment of eating matzoh on Passover.

MAGIDA: In their pursuit of a leavened-free house, traditional Jews thoroughly clean their homes of “chametz,” Hebrew for leavened bread. The night before Passover begins, they search their homes for chametz, which they might give to their rabbi to ritually sell to a non-Jew. Essentially, this is a matter of safekeeping the chametz during Passover, since it is purchased back when the holiday is over.

Rabbi WECHSLER: Since you are not Jewish, you will own it during the time of Passover.

MAGIDA: Rabbi Rachel Sabath has a modern interpretation. Chametz represents our inner demons, our own interior puffiness, the same puffiness that makes bread rise.

Rabbi WECHSLER: So we search our homes for everything that’s leavened, and that should be paralleled by a spiritual search for the puffy stuff in our own lives. What are our behaviors that we think need to be cleansed out? What I actually ask people to do is to write down 10 things about their lives to say, “This is the chametz of my life. This is the puffy stuff. This is the stuff that has to go.” And the next morning, when we go through the ritual of burning the chametz, that you’re also burning those things as a spiritual statement of “I want to burn those. I want to purge those things out of my life as well.”

MAGIDA: Instead of ritually selling their bread, some Jews may donate it to the needy, which is a way to perform the Jewish mandate to do tikkun olam, repairing the world.

Rabbi SABATH: In giving food over to those who are in need, we’re saying, as I think every Jewish act and every religious act should say, “We want to make the world a more whole and a more complete and a better place.”

MAGIDA: Jews have adapted Passover to changing times, while still being faithful to the purpose and core beliefs of the holiday. This is a holiday when families acknowledge the power of God and the freedom.

Unidentified Man #2: The most important part, we are protected always in God’s good hands.

Rabbi WECHSLER: We relive the events that took place to our ancestors in extremely personal fashion. Each of us sees ourselves as if we had come out of Egypt. The family gathers together, the community gathers together, and frankly, we’re all lifted up by the experience. We’re all really lifted by it.