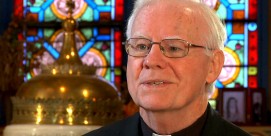

BOB ABERNETHY: Another icon of the American Catholic Church turns fourscore and two, 82, on May 25th. Father Theodore Hesburgh has been president emeritus of Notre Dame for a dozen years now, yet he's still a player on the world stage. Recently, correspondent Judy Valente went to visit the man they call "Father Ted."

JUDY VALENTE: He is a friend to the famous and a celebrity himself. At a reception, admirers jostle for a snapshot, a handshake, a few moments of conversation. But Theodore Hesburgh has spent most of his life amid the cornfields of northern Indiana, here on the campus of the University of Notre Dame.

Reverend THEODORE HESBURGH (University of Notre Dame): People always ask me, "Where do you live?" And I live right up there above the garbage can.

VALENTE: He's been an educator, an adviser to presidents and business leaders, and a globetrotting advocate for peace and human rights. He's demonstrated the skills of a linguist, a diplomat, an executive, and he's one of the most honored men of our time, but Theodore Hesburgh says he wants to be remembered for being one thing first and foremost, a priest.

Rev. HESBURGH: I really like a simple life, because I don't have any money personally; I don't have a bank account or a checking account or any of that. I think the greatest thing I can say about being a priest, what I like better than anything else, you belong to everybody. I've tried awfully hard to understand human problems and to find the right advice.

VALENTE: Hesburgh is 82 now, his step a little less steady, and he is blind in one eye. He retired as university president 12 years ago, but on campus, he remains a major presence and every moment a priest. On his morning walk, he stops at the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes.

Rev. HESBURGH: I pray here mostly Hail Marys, and I do it for friends of mine all over the world and for the day coming up, 'cause God knows what's ahead of me.

VALENTE: Recently, for example, it was a call from the State Department.

Rev. HESBURGH: A call comes indirectly from Secretary of State Albright, "We have a problem keeping this peace treaty that was signed at the Wye Plantation going, and we're gonna ask four Americans to go over and meet with four Israelis and four Palestinians and try to make sure we keep the peace."

VALENTE: Is there a danger for the clergy to get too close to power?

Rev. HESBURGH: Sure, you get close to power if you just hang around with power. I don't just hang around with power. And if you belong to everybody, you're gonna belong to more poor people than rich people, 'cause there are a lot more poor people than rich people.

VALENTE: In 56 years as a priest, he has said Mass virtually every single day. He describes the Mass as the center of his life.

Rev. HESBURGH: Every day, it reenacts God giving his life for us: "This is my body which will be given up for you," everybody. "This is my blood." He's present there, he's present as giving his body and blood for us. If you were to say to me, "You're gonna be dead in the next hour, what do you want to do?" I'd say, "Offer a Mass."

VALENTE: Hesburgh was just 32 years old when he became president of Notre Dame, in his words, "a rough and raunchy all-male school, known more for its football teams than its faculty."

He would develop the school into a major seat of higher learning. During his tenure, Hesburgh helped raise $350 million for Notre Dame's endowment. In 1967, he turned control of Notre Dame over to a predominantly lay board of trustees. In 1972, Notre Dame admitted women.

Mrs. CORETTA SCOTT KING: Let's see now, he's been involved with civil rights, nuclear disarmament, Third World development, improving the quality of higher education, immigration reform, and human rights.

Sister JEAN LENZ (Assistant Vice President, Student Affairs): He taught me that, like, individual people were really very important. I would watch him at times speak so globally about life, you know, and then all of a sudden he would turn around and say, "You know, I had a student come to me last night that's really got a problem. We've got to sit down and we've got to talk about this a little bit." And I— it— it just always amazed me.

VALENTE: As he walks across campus to his office, Hesburgh is stopped by a student whose mother has leukemia.

Unidentified Male Student: Could you say a prayer for my mom?

Rev. HESBURGH: I sure will.

Male Student: She— she was diagnosed with leukemia over the summer.

Rev. HESBURGH: Oh, I'm sorry to hear that. No, I'm sure the good Lord will take good care of her. No, but I'll be having Mass shortly, and I'll remember her special.

Male Student: Okay. Thank you very much.

Rev. HESBURGH: God bless.

Mr. MICHAEL TRIBE (Junior): I was up in the elevator, and this nice old gentleman started, you know, asking me where I was from and what my major was, and he said, "Hi, I'm Ted, and I'm from here." And it kind of dawned on me, you know, a couple seconds later, like, "Holy cow, I was just talking to Father Hesburgh."

Ms. MICHELLE MACK (Law Student): He's a legend, and he's the friendliest legend you've ever met.

VALENTE: But he is not interested in honors or recognition.

Rev. HESBURGH: They said they wanted to put my name on the library, and I said, "No way." And then they called a board meeting and didn't invite me in, and I'm walking over here one day and I look up, and the guy's up there, he's already got "Theodore M. He," and I said, "Oh, God, what's going on?"

VALENTE: Hesburgh's liberal positions have often put him at odds with the Vatican hierarchy.

I know you'd like to say, what— what would you do if you were pope for a day?

Rev. HESBURGH: I think I'd better not or I'd— I'd probably get thrown out of the Church tomorrow morning.

VALENTE: He feels the Roman Catholic Church is out of touch with many of the faithful.

Rev. HESBURGH: I think there ought to be beautiful churches—I'm not knocking that—but that's not the beauty of the Church itself. The beauty of the Church itself is the interior life of Christians who are committed to the Lord and committed to justice, committed to peace, and willing to suffer for that. And I think church could be a lot more simple than it is.

VALENTE: In spite of his prominence, Hesburgh was never named a bishop, or even given the largely honorary title of "Monsignor." Said a friend, "Liberals like Hesburgh aren't the people they're making bishops anymore."

Mr. PAT O'CONNOR: Hello, Father, Pat O'Connor.

Rev. HESBURGH: Pat. We always have Pat O'Connors in the crowd.

VALENTE: He has no hesitation in saying that priests should have the option of marrying and that women should be ordained, and he hopes his life offers one overriding message.

Rev. HESBURGH: I hope I've made a difference. Maybe God made the difference and just used me as a kinda handy instrument. I don't care how it happened, but I do go around saying, especially to students is, "Don't let anybody tell you you can't make a difference, 'cause you can."

VALENTE: As a member of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in the turbulent '60s, Hesburgh believes he made a difference.

Rev. HESBURGH: It was a monumental moral failure in America, not recognizing human beings as human beings, denying human beings the most basic rights that have to do with the pursuit of happiness. Try pursuing happiness if you can't get educated, you can't get a decent job, or you can't have a decent house. You can't get justice on the street.

VALENTE: At 82, Hesburgh remains what he has always been, priest and public servant.

Rev. HESBURGH (From Church Service): Mass is ended. Let us go in peace to love and serve the Lord, and each other. Thanks be to God.

VALENTE: I'm Judy Valente for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, in South Bend.