In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The Catholic Vote

BOB ABERNETHY: Political experts say Roman Catholics are among the most important swing votes in this election. Catholics support the Democratic Party overwhelmingly, but Kim Lawton reports there are growing political divisions among the nation’s 60 million Catholics.

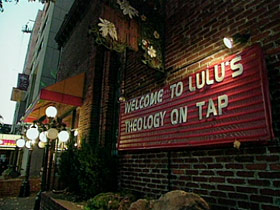

KIM LAWTON: At Lulu’s Bar in Washington, D.C. this fall, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese has been sponsoring a series of discussions about applying the Catholic faith to modern life. It’s called “Theology on Tap.” On this night, the topic was Catholic identity.

LAWTON: Not long ago, Democratic Party affiliation was among the factors tightly bound into Catholic identity. But times have changed. Many of these young Catholics say they are moving away from their family’s traditional support of the Democratic Party.

SALLI MCCRAY: There is a big division. It is not a division that causes family fights. It is a division that you are like, “I can’t believe politics has really come to this that in order to vote my conscience, I have to become a Republican.”

LAWTON: According to a new study by Georgetown University’s Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, CARA, 37 percent of Catholics think of themselves as Democrats, while 28 percent think of themselves as Republicans. That’s a big change from just 30 years ago, when most Catholics were staunch Democrats.

Peter Steinfels worked on the CARA study.

PETER STEINFELS (Georgetown University and NEW YORK TIMES columnist): Catholics have loosened their link to the Democratic Party without really forging a link to the Republican Party. That’s why they are considered a somewhat volatile vote, a swing vote.

LAWTON: While Catholics still do lean slightly more Democratic, there’s no longer any one Catholic voting bloc. With more than 60 million Catholics in the United States, that’s a lot of votes up for grabs, particularly in key electoral states. Which is why the candidates have been paying special attention to the Catholic community.

JOHN GREEN (Ray C. Bliss Inst. Of Applied Politics): These campaigns understand that in many states, Catholic swing voters may be critical, so they are trying to appeal to them in distinctive ways.

LAWTON: Like other immigrant communities, many American Catholics gravitated early on to the Democratic Party. The relationship was strengthened after the first Catholic run at the presidency, by Al Smith, in 1928, and then with Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal in the 1930s. Roughly 80 percent of Catholics voted for John F. Kennedy; but since then, there’s been a gradual pulling away from the party.

Father Robert Drinan, a Democratic Congressman from 1971 to 1981, says there are several possible reasons for the change.

Father ROBERT DRINAN (Former Democratic Congressman): One is abortion. Reagan said, “I will re-criminalize abortion.” Some, maybe five or seven percent of the Catholics moved because of that. Likewise, he promised there would be some assistance to church-related schools. Another group of Catholics moved toward the Republicans. And third, they became rich and moved to the suburbs. But I think in a vast, decentralized country like this, you are bound to get more pluralism and diversity.

LAWTON: And as an old Democratic hand, how do you feel about that?

Father DRINAN: Well, the Democrats have to go with the flow and do things that are better.

LAWTON: CRISIS MAGAZINE, which has a large conservative Catholic readership, has done its own study of Catholic voting patterns.

DEAL HUDSON (CRISIS MAGAZINE): From our research, it appears this migration of the Catholic from the Democratic to the Republican Party has been fueled by a decline of moral values, decline in education, decline in respect for basic family values, fueled in part, by government programs that have exacerbated those problems.

LAWTON: Catholics who attend Mass regularly tend to lean the most Republican. Experts aren’t sure exactly why.

STEINFELS: We’re not sure to what extent the distinctive patterns of Catholic voting arise from church teaching specifically or something in the Catholic religious life, or to the extent that they arise from movements into the middle class, the breakdown of ethnic communities and ethnic identities.

LAWTON: Ethnic political influences appear to have lessened among earlier immigrant groups such as Italians and Irish, but some clear cultural differences remain. Hispanic and African-American Catholics tend to be more liberal, while Asian-Americans tend to be more conservative.

For many Catholics, part of the political tension lies with the fact that church social teaching is liberal on some issues, but conservative on others, so it doesn’t neatly dovetail with the platforms of either party.

Ms. MCCRAY: There are certain things from either party that attract me and certain things that repel me. It seems to me that when I take my conscience into the voting booth, there is always something that has to be clipped from it.

LAWTON: In recent election years, the Catholic bishops have issued a statement listing several issues Catholics should take into consideration as they vote. Abortion is one of them, but so are opposition to the death penalty and support for social justice and workers’ rights.

Application of these principles spreads Catholics across the political spectrum. This fall, the Catholic peace movement Pax Christi is sending its “Moneymobile” across the nation with a theatrical presentation urging that military spending be cut, with the money instead going to social programs.

A group called Priests for Life, meanwhile, has launched an election season ad campaign urging voters to elect pro-life candidates.

GREEN: There is a group in the middle, the Catholic centrist, if you will, who contribute an enormous number of people to the swing voters we’ve been reading so much about. These are folks that would like to vote Democratic for some reasons and would like to vote Republican for other reasons, and they are fairly conflicted, and they could really go either way.

LAWTON: A fact not lost on the presidential campaigns. Both parties have been aggressively reaching out to Catholics. This year, both Al Gore and George W. Bush appeared at the annual Al Smith dinner in New York, a non-partisan event that raises money for Catholic health care programs.

No matter what the outcome of the election, many Catholics are pleased to see the parties competing for Catholic support.

HUDSON: It is good news for the Catholic community because for the first time in my memory, Catholics are being taken seriously as a group that have specific concerns. They have specific concerns they want addressed by candidates on both sides of the aisle, and they are being addressed.

LAWTON: Catholics make-up about one-fourth of the U.S. population, and provide nearly 30 percent of the total votes in national elections. With large Catholic concentrations in key battleground states, many say American Catholics could well determine the outcome of the coming election.

I’m Kim Lawton, in Washington.