Religious Views on Stem Cell Research

BOB ABERNETHY: As President Bush approaches a decision on whether the Federal government should fund research on embryonic human stem cells, religious groups are on both sides of the debate.

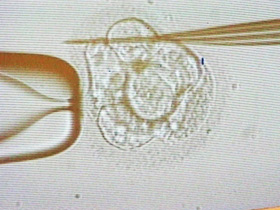

For many, the fundamental issue is the moral status of tiny, one-week-old human embryos, no bigger than a pinprick. In each one are so-called stem cells that can grow into any kind of human tissue. Scientists think these cells can help them find cures for many severe illnesses. But harvesting those cells kills the embryos.

Ethicists say the right and wrong of destroying even unwanted embryos in order to do promising medical research depends on what you think those embryos are. If they have the moral status of persons, many argue, then they can not be treated as a means to even the most humanitarian end. If they are other than future persons, then doing the research may seem the greater good.

Here is a sampling of the religious lineup in the stem cell debate:

The U.S. Roman Catholic Bishops oppose the research as “immoral, illegal, and unnecessary.” They say life is sacred from the moment of conception.

The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod and the Southern Baptist Convention are also opposed, for the same reason. “Human embryos,” says the SBC, “are the tiniest of human beings.”

On the other side, the Presbyterian Church USA approves the research when the goals are “compelling and unreachable by other means.”

This week, the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations agreed, saying, “an isolated fertilized egg does not enjoy the full status of personhood.”

The Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism also approves, saying what would be “immoral and unethical” is cutting off funds for promising medical research.

More now on religion and the stem cell debate from Kim Lawton.

KIM LAWTON: Joining me are Sondra Wheeler, Professor of Christian Ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary here in Washington, D.C., and Lisa Sowle Cahill, Professor of Theology at Boston College. She joins us from Boston. Lisa, we heard a lot from the pope this week about the issue. What is the theology behind the Catholic Church’s position that an embryo has the moral status of a person?

Professor LISA SOWLE CAHILL (Boston College): Well, I think there are a couple of concerns. To speak first of all in religious terms, if you think of doctrines like creation or even human sinfulness and the fall, it really encourages us to put the way we treat life against a bigger horizon and to be cautious about our own activity. The whole idea that the embryo is a person is really a philosophical idea more than a strictly religious one. It’s based on an idea that as soon as you have an individual human life you have a person. The church even says that we don’t know that for sure philosophically, but we should give the embryo the benefit of the doubt and be especially protective of it.

LAWTON: Is there a distinction to be made between an embryo developing in a woman’s womb and when it’s not developing, it’s in a petri dish in a lab?

CAHILL: Well, of course there is the interest of the woman at stake, and that’s very important if she is pregnant. But from the standpoint of the embryo alone, the Catholic Church, at least the official church, would say no, that that embryo is still the same kind of being no matter where it exists.

LAWTON: And Sondra, Protestants have come down all over the map on this. What are some of the theological positions they’re taking?

Professor SONDRA WHEELER (Wesley Theological Seminary): Well, they range from a position that would say it’s already problematic to fertilize an ovum outside the body, to create an embryo outside the body because it removes the germination and transmission of human life from the context of the marital relationship, from the personal union of husband and wife. And in that way it is very close to the Catholic underpinning of their objection. There are also those who regard the creation of embryos for reproductive purposes [as] acceptable, who are willing to tolerate in vitro fertilization as a way to get around medical problems with conception but who are either completely prohibitive or very, very restrictive of the destruction of embryos, who want either to implant all fertilized embryos or to create essentially no more embryos than is minimally necessary to accomplish the reproductive purpose. So they’re going to oppose stem cell research because of the destruction of embryos. And then there are those who are cautiously tolerant of stem cell research, provided that it’s done within the 15-day window of embryonic life before implantation would occur and done only on embryos that cannot be used for the reproductive purposes for which they were created.

CAHILL: Yeah, I think Sondra brings up a really good final point there, that often we have conflict cases. Everyone appreciates the value of healing and offering remedies for disease, but on the other hand, we think there is some sort of level of beginning life at stake and we want to be protective of that. So I think that many would say in various religious traditions that using discarded embryos is a lot different from creating embryos for research, that that’s at least one way to try to reconcile those values.

LAWTON: The Bible talks about valuing life, but the Good Samaritan tries to go out of his way to alleviate suffering. What kind of determination do you make to determine which trumps which value?

WHEELER: Well, that’s going to depend on how you regard embryonic life. We don’t trade one human life to save another. You don’t kill one patient in order to transplant an organ into another even to save lives, and you wouldn’t do it even if you could save two lives that way. So it depends partly on what you think you are dealing with.

CAHILL: I think another big framework here that we need to get on the table is that most religious traditions, but especially Judaism and Christianity, have a commitment to helping the most vulnerable and the most powerless. And in fact the concern for the embryo fits into that picture. But even more today is the bigger picture of who will benefit from stem cell research if it is developed, if therapies are developed. We have a lot of uninsured people in this country, and the Good Samaritan helped the one who had no way to help himself. We have sayings in the Bible about whatever you do for the least of these you do for me, and so on. So another concern here for religious people and for others is who’s investing in the research, who is going to have access to it? Who will profit from the therapies that are eventually are available?

LAWTON: And briefly, Sondra, does that affect how people think?

WHEELER: Most certainly it does. If you think that this is a straightforward, do we rescue an eight-cell embryo or do we save a Parkinson’s patient, that looks one way. But it’s not the case that the motives and the impetus behind this research is perfectly pristine and altruistic. This is biotechnology, it is a commercial enterprise as well with power and prestige and significant money to be made from it, and therefore there’s a question about what happens when we make early forms of human life strictly the means to an end.

LAWTON: Okay. Thank you. We’ll have to leave it there. Thank you both.