In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Islamic Finances

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, another business story. Some devout Muslims believe the Koran forbids them from paying any interest. But they can still manage to finance buying a house if they can find — not a lender, but a partner. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports from Houston on Emran (not Enron) — Emran and Israt Gazi, Muslims and new homeowners.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: Emran and Israt Gazi are an immigrant success story. He is a petroleum engineer who owns a successful business. She is a physician hoping soon to begin a residency. And they now live in their dream home.

ISRAT GAZI: It is a four-bedroom house; it has two living areas and the master bedroom is downstairs and three bedrooms upstairs.

DE SAM LAZARO: However, it took almost 10 years of scraping by in rented apartments before the Houston couple and their three children were able to move in. It wasn’t that the Gazis had bad credit. They simply don’t believe it’s right to pay interest. Their credit card bills are paid in full each month.

The Gazis, originally from Bangladesh, are devout Muslims. He is president of their mosque council, and has always adhered strictly to the Koran’s prohibition on “riba” — the receipt or payment of interest. It was at the mosque that the Gazis learned about MSI, a Houston lending cooperative that specializes in so-called Islamic financing.

EMRAN GAZI: This is like rent to own, you know; I pay same rent, except difference is I paid 25 percent down first. Slowly I am getting more ownership.

DE SAM LAZARO: Although there are variations in the details, MSI’s is a typical model for Islamic financing: borrowers usually make a down payment of 20 to 25 percent. For its part, the bank becomes a joint buyer of the home. But the monthly payments are not pegged to an interest rate, as in a mortgage. Instead they are based on the home’s rental value, calculated through a market survey of similar homes for rent.

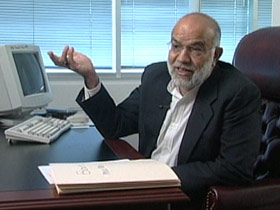

Professor MAHMOUD EL GAMAL (Islamic Economics, Rice University): Say if the house we’re talking about rents for $1,000 a month and you own 80 percent of it, then I have to pay you $800 in rental and then maybe I can pay you $850, where the $50 is the reduction of the total amount that you own in the house.

AYUB BADAT (MSI Financial Services): So the next year when he will send the payments, then his share will go up and our share will go down. Eventually in 10 to 15 years, he will be the owner of the house.

Professor EL GAMAL: Basically you’ve taken out the interest payment part and replaced it with the rent part.

DE SAM LAZARO: What’s the difference?

Professor EL GAMAL: That is the obvious question, the best question. It may seem that all we’ve done is take out the word “interest” and put “rent” in its place. The difference is how you decide on that rent.

DE SAM LAZARO: It’s a bit like splitting hairs, El Gamal says, but that’s not uncommon when it comes to interpreting religious law. In fact, the prohibition on riba is not unique to Islam. Both Jewish and Christian scriptures admonish believers to avoid usury, although both faiths have relaxed their interpretation.

Even Islam lacks a consensus on the intent of the Koranic pronouncement. Only a minority of Muslims are thought to rigidly avoid all interest-based credit.

Professor EL GAMAL: There is a group of Muslims who view the prohibition of riba as historically predicated on the circumstances in Arabia at the time, which is that lending with interest was mostly an activity of loan sharks who used it to exploit the needy. They don’t see the mortgage loan contract to be exploitative in any way and therefore don’t feel that that is the forbidden riba. But even those people who feel that way have lingering doubts in their minds so that if Islamic financing could be provided competitively, I think many people would migrate over just for the peace of mind.

DE SAM LAZARO: Sensing a sizeable market in Islamic financial products and services, many mainstream companies have entered the field. There are brokerages and mutual funds that avoid stocks in companies involved with alcohol and pork products, for example.

The growing acceptance of Islamic finance should gradually make it easier for families like the Gazis. Even after making their down payment, they had to wait a full year before the bank raised enough money to put up its share of the purchase. About their banking relationship, though, they have nothing but good things to say.

Mr. GAZI: Each year, we do appraisal and if the value of the house goes up, then we share the profit; but if it goes down, it is negative for them but they still share it.

Mr. BADAT: The other major, major difference is we also share the taxes. Another important factor is if some major thing happens to the house.

DE SAM LAZARO: Repair?

Mr. BADAT: Repair — we also share that. Another thing is insurance. That we also share, according to our share program. If he has problem with job loss, with a bank they will kick him out in six months. We work with him.

DE SAM LAZARO: Ultimately, Islamic financing spreads risk evenly between borrower and lender. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Houston.

ABERNETHY: Of course, if you don’t have a mortgage you get no income tax deductions for mortgage interest. But it’s not a total loss. If you can find a partner the way the Gazis did, you get to share your costs for real estate taxes, repairs, insurance and any drop in your house’s market value.