In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

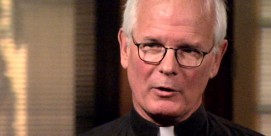

Father Andrew Greeley Extended Interview

Read more of Judy Valente’s interview with Andrew Greeley:

Q: Father Greeley, what is the essence of being an American Catholic? What makes a Catholic distinctive?

A: I think it’s the stories. If we get you in the early years of your life and we fill your head with all of the Catholic stories, then it’s very hard for you to stop being Catholic. Catholics are Catholics because they like being Catholic. They like the stories — Christmas, Easter, May crowning, the souls in purgatory, the saints, the angels, the mother of Jesus. These are enormously powerful religious images. Some people might think they’ve become clichés through the century, and maybe for some they have. But for most Catholic lay folks, the images and the stories are what hold us in the Church despite, sometimes, our leadership.

Q: If you were trying to define the essence of American Catholicism, what would you say?

A: Well, I’d say that Catholicism in the United States has the distinct advantage of being in a pluralistic society, where your religion contributes something to your identity. So you tend to define yourself as a Catholic. I’m Irish, Catholic, a Democrat from the West Side of Chicago, and that’s pretty much my identity. But for most Americans, that relation is part of their identity, so you come to them and say, “Where are you from?” or “What are you?” when [they] move into a neighborhood, and they’ll say Protestant or Catholic or Jew. It’s the preprogrammed response. I don’t know how I would explain it to people who live in a country where everybody’s one religion, but I would try to say that religion is a part of who we are and what we are. It gives us something to belong to and something to believe in in our lives.

Q: What is the religious core of Catholicism? What is the kernel and what is the husk?

A: The kernel is the belief that God is love and, in Catholicism, God’s love is present in the world. It is in the sacraments, in the Eucharist, in our families, in our friends, in our neighborhood, and forgiveness in the touch of a friendly hand, in a rediscovered love God is there. God lurks everywhere. That’s the fundamental Catholic instinct on the imaginative and poetic level — that God is lurking everywhere. Right down the street, right around the corner, there’s God.

Q: You’ve used the term “communal Catholic.” What do you mean by that?

A: Well, I meant people who have decided they’re going to be Catholics on their own terms. They are Catholic, they’re strongly Catholic, they like being Catholic; but they’re not going to let Church leadership dictate the terms of belonging. Immediately after the Second Vatican Council, [there was] the euphoria and the effervescence of the council, the contagion [from] the council fathers to the people and to the lower clergy, and in a remarkably short period of time, they changed the Church. By 1975, all this had happened: birth control wasn’t wrong, premarital sex wasn’t wrong, priests leaving the priesthood wasn’t wrong, nuns leaving the religious life wasn’t wrong. You didn’t really have to go to mass every Sunday. You didn’t have to go to confession before receiving communion every time. All of these things, which they never really understood and they didn’t like, were just swept away. Now, a whole generation later, despite all the efforts of the present pope, they [the Church fathers] have not been able to restore the acceptance of those teachings. And I don’t see how they ever will. It may be good, [it] may be bad, but the sociologists say this is what’s happened.

Q: Where does the idea of “communal” come in, though?

A: Well, they’re part of the Catholic community, but they’re not necessarily obedient to the teaching Church. If you’re a Catholic in Italy when you’re born, it’s unthinkable to stop being Catholic. You just take the rules a lot more seriously, because it pervades your culture.

Q: Let me ask you about another phrase you’ve used — the “Catholic imagination.” What is the Catholic imagination?

A: The Catholic imagination is metaphorical or sacramental. It sees God as present in the world. The Protestant imagination, the dialectical imagination, wants to preserve God from the possibility of idolatry by identifying with His creatures. Catholicism has no problem with that. It sees God present in His creatures, in all of the creatures, and especially in those creatures that love us and that we love.

Q: What do you think are the most serious problems facing the American Catholic Church?

A: Women. And the woman problem is also a man problem, because men have stronger feelings about the rights of women in the Church than women do. Not much stronger, but some. The Church just has not been able to cope with the demands for fairness and equality from women, so they’re very angry. For a long time, the bishops could console themselves — and I think some still do — that these are just radical feminists. But the radical feminists include their sisters and their nieces and their mothers and all the women in their lives. They just don’t like the way the Church treats them. And this includes lots of parish priests. They are just awfully sloppy in their respect and sensitivity toward women.

Q: What else?

A: The next thing is the quality of preaching and worship. Thirty years ago, before the Vatican Council, Catholics didn’t know what liturgy was. Now they know what it is, and they want it [to be] good. They want good preaching and good liturgy. The parishes that provide those things flourish. But so many priests, for one reason or another, don’t do it.

Q: Christians, of course, make up the vast majority of people in this country; but there’s a growing religious diversity. Although Americans are tolerant of other religions, should Christians be evangelizing, trying to convert others to Christianity?

A: I think the only kind of acceptable evangelization is the evangelization of good example. The kinds of lives we live, the joy, the patience, the charitableness of our lives is the way we influence other people. The early apostles said, “See how these Christians love one another.” My colleague Rodney Stark at the University of Washington has done research on the spread of Christianity. He has empirically validated that finding. People came into the Church in the Roman Empire because the Church was so good — Catholics were so good to one another, and they were so good to pagans, too. High-pressure evangelization strikes me as an attempt to deprive people of their freedom of choice.

Q: Let’s take it a little bit further. Do you think Americans believe that there is truth in all religions? And, if so, does this violate the idea that the only way to salvation is through Christ?

A: Well, I think Catholic Americans had better believe there’s truth in all religions, because the Second Vatican Council said that. We don’t believe that we have a monopoly on truth. We believe what we have is true, but it’s not the whole truth. And we can learn a lot from the other religions if we listen to them respectfully. We don’t give up our heritage; we expand it. There’s the great story about Saint Augustine of Canterbury. He [went] to England when the Anglo-Saxons had taken over, and he liked them; they seemed to be good people. He wondered whether it was all right to adapt their customs to Christianity. And Gregory the Great, who was pope then [in] 600, wrote him a letter saying, “Well, of course. As long as these are good and true and beautiful, and there’s nothing unnatural about them, then of course they can be adapted for Christianity.” That’s been our policy ever since. Sometimes we’ve violated it, but that’s the official policy. We can learn from everybody. Catholicism means, “Here comes everyone.”

Q: But how can a Christian, a Catholic reconcile that with Christ’s saying, “I am the Way, and the Truth, and the Life; no one comes to the Father, but through Me”?

A: I don’t think Jesus was an exclusivist. He said, and we believe, that He is the unique representation of God in the world. But that doesn’t mean this is the only way God can work: “Now, God, you’ve got to work here and no place else.” Nobody puts constraints on God. She doesn’t like it.

Q: Are Americans tolerant of other religions, or merely indifferent to them?

A: Oh, I think they’re at least tolerant. It’s the viewpoint that everybody has the right to make their own religious choice, and we’re not going to challenge that right. I think we find some of the other religions interesting — not all of them, but some of them are interesting. We’re more than tolerant. I don’t think it’s indifference.

Q: What do you think is the best long-term response to terrorism that seems to be fomented by religious beliefs?

A: I don’t think we can really change the beliefs of the people who think we’re the “Great Satan” and have to be destroyed. We have to protect ourselves against them. We’ve got to be much better at both security and intelligence. But the long-term [response], I think, is forgiveness. If we are followers of Jesus, we say the Lord’s Prayer every day. We should realize what “Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who have sinned against us” means. We don’t earn forgiveness by forgiving. It’s not a barter deal with God. God’s already forgiven us. It’s our job to manifest that forgiveness of His, that implacably forgiving love of God’s, to the rest of the world by forgiving people who’ve hurt us. That doesn’t mean we don’t engage in self-defense, but it does mean that there is no room in a follower of Jesus of Nazareth for hatred or vengeance. We certainly have to engage in whatever military attacks are necessary to protect us from further assaults on our people. But we do so in the name of self-defense and not in the name of vengeance. Revenge, vengeance — this doesn’t fit the Christian tradition. Somebody said to me in a recent e-mail, “You’re just preaching that old Jesus drivel.” Well, “Jesus drivel” it may be, but Jesus said of the people who killed Him, “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.” If we’re not willing to say that, then we’re not on the same path Jesus walked.

Q: Do you believe Americans’ religious beliefs are softening? Are people less wedded to creed and doctrine? And if you believe that, why is it happening?

A: I know that’s the conventional wisdom, and some of my sociological colleagues have been writing about [it]. I don’t believe it. I think that the core doctrines of Christianity — the incarnation, the resurrection, life after death — these are as strong as ever. In fact, the belief in life after death has increased in this century. I don’t think American religion is falling apart. Quite the contrary. I think the real problem for American religion are those minority of fundamentalists who try to identify political policies with religion. They’re offending people, and they’re responsible for some of the departure of younger Protestants from denominations. The Catholics we lose — it’s almost always over divorce and remarriage, of which problem we have made a real mess.

Q: What is turning people off to the Catholic Church?

A: Most people who are born Catholic are still Catholic, unless they’ve had a divorce and remarriage problem. I think the Church is just ham-handed in dealing with those people. They leave the Church because of something that’s happened to them in the process of getting a divorce and being remarried.

Q: Is that all it is, or is it the whole gamut of sexual issues?

A: There has always been a certain proportion of people who leave the Church on issues of authority and sex. That hasn’t changed since we started doing research on it back in the early 1960s. The increase comes from people who’ve had marriage problems. [Catholic University sociologist] Dean Hoge and his colleagues have done work on young Catholics, and they find that very few young Catholics don’t think of themselves as Catholic anymore. They want to stay even if they don’t go to church much.

Q: Let’s talk about the influence of Hispanics on the Catholic Church. What is their major impact?

A: I think they are a great grace for the Catholic Church in this country, because their religion has so much festivity and celebration in it. We European Catholics tend to be somewhat grim and dour and straightlaced. We shouldn’t have been, but we are. We can learn from the Latinos that Catholicism is a religion of festivity and celebration.

Q: Are Hispanic Catholics different in any other ways?

A: They have a very strong sense of family and local community. Now, of course, so do the Italians and the Irish. But I think it’s stronger. One Hispanic woman… was telling me about her religion, and all she was talking about were the parties, the festivals. And I asked, “But what does all this mean?” She would tell me about another party or festival. I finally said, “No, no. What’s the theology?” “Oh,” she said. “Well, I think we believe that God is part of our family. And when we have celebrations, God comes and celebrates with us.” I like that. I think we should have more of it.

Q: So many Catholics in this country disagree with fundamental teachings of the Catholic Church, especially those having to do with sex, gender, reproduction. And yet, they remain loyal to the Catholic Church; they would never join another church. Why is that?

A: Because once a Catholic, always a Catholic. If you’re a Catholic and are filled with Catholic images and stories in childhood, you don’t want give them up. You like being a Catholic. And how fundamental are these teachings? What’s more important? Life after death or birth control? What is more important? God’s forgiving love or premarital sex? The sexual ethic is important, but it’s not the only thing in Catholicism. I’m afraid sometimes our leaders — and the media, too — have made it sound as if the only unique thing about Catholicism is sexual teaching. The lay people know better.

Q: Why have people stopped going to confession? Why do they think it’s not necessary?

A: I think one of the conclusions that many Catholics drew from the Second Vatican Council is there’re just a lot fewer mortal sins than there used to be. So we don’t really have to confess them, and we can make a good act of contrition, as we used to say, and receive communion, and it’s fine. Part of it is just the decision that confession before communion isn’t necessary. This is a conclusion that the laity have reached. And the lower clergy have not disabused them of that notion, because they think the same thing. People still go to confession and the penitential services at Easter and Christmas. They’re very, very popular. But we realize now that we really don’t have to run to confession every Saturday afternoon if we want to receive communion on Sunday.

Q: What is the benefit of confession?

A: I can think of two benefits, and both have to do with reconciliation. One is you’ve been away for a long time, or you’ve done some terrible sins, and you want to do penance for them. You want to get them straightened out. You want to acknowledge that you were a sinner or a wanderer and eliminate that dimension from your life. For those kinds of people, the old kind of confession — maybe not in a box — is very, very helpful. It relieves a lot of stress and guilt and gives you a sense of beginning all over. For most of us, confession is a chance to be reconciled with the local community. Those priests who support the absolution services — that’s why they’re so popular, because people want to be reconciled with the community.