In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Kristin Hahn Interview

ON THE ROAD IN SPIRITUAL AMERICA

Read an interview with Kristin Hahn, author of the new book IN SEARCH OF GRACE: A RELIGIOUS OUTSIDER’S JOURNEY ACROSS AMERICA’S LANDSCAPE OF FAITH (William Morrow):

What is religion, what is spirituality, and what is the difference between the two?

In the introduction to IN SEARCH OF GRACE, I share the conversation-stopper I had with Dr. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross when she chided me for interchanging the words “religious” and “spiritual” in my questions to her. From her perspective, “religion” encompasses belief in doctrine too often driven by fear of eternal consequences, whereas “spirituality” speaks to an individual’s direct experience, something of a more empirical nature. Dr. Kubler-Ross was my first interview, so I hadn’t yet gathered my own experiences to argue otherwise. Four years later, however, having delved into twenty different faiths from various geographical niches across the country, I’d now respectfully say to Dr. Kubler-Ross that even within the most “institutional” religions, I found somewhere at their core an intensely spiritual inclination to engage the ethereal in a distinctly independent and direct way. And in the heart of this kind of believer is a consciousness of their moment-to-moment decision to be the kind of person who boldly patterns life around the elusiveness of faith. Be it a monk or nun of East or West tradition, or a Mormon missionary, or an Amish farmer, or a Hindu yogi, this heightened consciousness is attained through the discipline and cumulative effect of daily practice, such as prayer, fasting, meditation, ceremony, proselytizing, or prostrating.

To me, religion is a set of beliefs; spirituality is what we make of them. To be a spiritual person is to be an optimist of the highest order, to trust in certain truths that often defy the realms of literalism and science. For spiritual optimists of every creed who don’t just paint by numbers, but choose to remain poised in an “awake” state of mind and action, daily life is defined by the most active stillness imaginable.

Your book includes a foray into the monastic world. Is the “new” spirituality in America as much about the retrieval of ancient, perhaps neglected contemplative spiritual practices as it is about searching for spirituality in the strange, the new, the unfamiliar and exotic? And is it still possible for the great sermon, the moving hymn, the recited creed, the standard liturgy to be a deeply spiritual experience in America?

Spending time with Benedictine monks and nuns, and Buddhists avowed to contemplative life, I encountered a definite interest in unearthing the neglected practices of their traditions. I found this to be the case particularly among younger nuns and monks. Two twenty-something Benedictine nuns spoke of the ancient and pointedly mystical practice called “lectio divina.” As it was explained to me, one sits for a period of time in a state of meditative prayer and then reads a “randomly” selected passage from the Bible or one of the spiritual classics. It is believed the passage will “speak” to its recipient in a very personal way as a message of wisdom, guidance or joy from the Holy Spirit. This kind of communion lends itself to the idea that a single sentence, or even word, can be interpreted differently by individuals under varying circumstances, and this defines the divine collaboration between reader and the Word, the vertical and direct connection between each believer and the one God. Lectio divina is an extracurricular practice that can help nurture one’s ability to sense and receive such a Presence. And though it was not on the daily schedule of devotion, the nuns I spoke to made time for it.

Because (ideally) every generation is represented in an abbey, young nuns can turn not only to the written word for guidance, but to their elder housemates who often have intimate knowledge of forgotten practices. And the older nuns are then exposed to a new, energized, and curious generation of believers who are often more inclined to openly share their feelings, their fears and doubts, their questions and experiences. This kind of intersection seems to be a source of constant renewal for those living in a monastic setting.

After three years of intensive research and firsthand experiences, I was struck again and again by how eclectic Americans are when it comes to their pursuit and expressions of faith. These days “new” spirituality includes old and new paths, though “new” often means repackaged, refashioned old. I found this to be the case with “postmodern” religions like Scientology and book-driven spiritual movements like CONVERSATIONS WITH GOD. Scientology’s founder, L. Ron Hubbard, drew from every old tradition he uncovered over decades of researching mystical religions and the science of the human mind. Assembling foundational religious beliefs such as man as eternal spirit, reincarnation, and karma (cause and effect), Hubbard wrote his own creation story with self-determination as the thrust of its accompanying practice. The futuristic vibe, incremental revelation, and inexhaustible volumes of “technology” are all appealing to those who are perhaps looking for something “new and different.” And yet the fundamental concepts behind Scientology’s practices and ethics are actually not that mysterious or unique.

One of America’s predominant themes is to refurbish the old, to reinvent and renovate, to dust off and restore the antique, to make forgotten things valuable again. So it makes sense that many of us would keep that approach when it comes to our faith.

Who are some of the other people, what are some of the practices, traditions and places that didn’t get into your book on the American spiritual scene but just as well might have?

To be frank, when I heard about Brad Gooch’s book, I got a little nervous; one, he’s by far a more seasoned writer, and two, I feared we had covered similar ground in our attempts to capture spirituality in America. I was relieved when I read his book and found that — while he remains the superior writer and we do share some of the same questions and curiosities — we somehow (by the grace of God?) approached different circles of faith and interviewees, and chose distinct scopes of investigation — his more concentrated, whereas I went for the broader, bigger picture. For example, I tried to interview Gurumayi but could never make it happen when she was in the U.S. I thought of approaching Deepak Chopra and considered focusing my monastic chapter on the Trappists and Trappistines (all of whom appear in Brad’s book) but, more by chance than anything else, I chose other roads. I sent out hundreds of letters, made hundreds of follow-up phone calls in an attempt to secure interviews and invite myself to various ceremonies and into sanctuaries, but my experiences and observations were largely dictated by the willingness and availability of those I contacted.

There were a number of faiths — mostly offshoots of primary faiths –that I researched and considered, but eventually the length of the book just became too unwieldy. So I shelved a lot of material with the hopes of a second volume. One religious order that I was really taken by but ultimately did not include in the book was Sufism, a mystical outgrowth of Islam. (Brad Gooch very adeptly covers Sufism in GODTALK.) I really loved the time I spent with a group of Sufis in the Boston area. We would meet once a week for a world religion ritual, lighting a candle in honor of each of the primary faiths and then reading a section from their sacred texts. I was blown away by the level of love and respect these individuals expressed for all of humanity and every belief system, bearing no judgment of another’s perspective or choices. The Sufis I met believe that all paths lead to the same ecstatic place of Oneness.

I also explored Quakers with a focus on their most foundational practice of pacifism. Again, for the sake of space, pages had to be cut. I also dipped my toe into some of the more alternative faiths that have sprung up over the last few decades, like religions centered around a belief in UFOs and communication with extra-terrestrials. In the end, I felt these kinds of religious movements were more suited to a book specifically dedicated to alternative faiths. I was more interested in isolating accessible religious practices and looking into the effects — real or perceived — that they had on their practitioners.

One disappointment I have about the composition of the book is the ratio of women to men. Most of the women I invited to be interviewed declined. Some of them are well known, like Marianne Williamson, and others are reverends and rabbis who, like the Rev. Peter Gomes, moved me with their sermons. (The exception to this frustration was Mrs. Virginia Harris, the chairman of the Christian Science Board of Directors, who very openly allowed me to interview her. She is, essentially, the only female head of a world religion.) I suppose it’s just a matter of bad timing or a case of the particular women I approached feeling overextended, but I never seemed to have a problem finding men who were willing to talk. I tried very hard to balance the ratio by focusing on lay women from different faiths such as in the chapters dedicated to Mormonism, Islam, and Wicca.

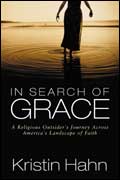

I can’t help but ask about the arresting photograph on the jacket cover of the book. Is there a story behind this image? What does it say to you, and what does it have to do with what you learned about American spirituality while writing IN SEARCH OF GRACE?

After I turned in the manuscript for IN SEARCH OF GRACE, my editor and I struggled to come up with an idea for a jacket cover image that would be universal enough to represent — or at least not offend — the twenty distinct faiths explored in the book. She came across a photograph and sent it to me and we agreed our search was over. The sepia image is of a nondescript woman wading into a vast body of water. We see her from the waist down, her slow steps causing ripples to form layers of circles around her ankles. The surface of the water is illuminated by the golden light of a setting sun, but underneath is deep darkness.

Many creation myths include birth from some source of water, life emerging from the dark depths into light. And, of course, biologically speaking, we humans are about 85% water. Water is also the essence of baptism or rebirth, and not just in the traditional Christian sense. For me, the process of writing this book — of submerging myself in a multitude of faiths and their practices — was a kind of baptism. I indeed felt encircled by what I was stepping into, each tradition offering so many layers to be peeled.

In the image, the woman’s arms are slightly lifted in a way that, to me, suggests not trepidation, but openness. I think as an unaffiliated outsider to religious affiliation, the strongest quality I brought to the writing of IN SEARCH OF GRACE is an openness and a simple curiosity that is not weighted by too much religious “baggage” or judgment; whatever preconceived notions I had stemmed from my exposure to popular culture, and I come clean about these in each chapter.

Because the religious waters I waded into were unfamiliar to me, much of the time I felt as if I’d stepped into a deep, dark morass; I was often overwhelmed by the extensiveness of each of the twenty faiths and felt as if I could easily spend my lifetime investigating any one of them. So because I felt that my ladle had to be big and sturdy, I was forced to spend a lot of time feeling simply swamped by the volume of information and experiences I was trying to hold and distill. It was my interest and focus to look at the big picture, to try and ascertain what was unique to a variety of faiths and what was common among them, looking at each through an experiential lens. The idea was to venture out there into what was, for me, the great unknown, to saturate and then bring back an informative and entertaining record that would ultimately be easily digestible for those who are perhaps as unfamiliar with the territory as I was.

I believe the body of water in the book’s cover image represents the commonality and highest intention — the integration, eternity, unity, and oneness — behind each of the faiths I feel fortunate to have encountered. And the culmination of the book is a literal birth, but you’ll have to read the epilogue for details.

Do you still think of yourself as a religious outsider, and is there something peculiarly American, perhaps, about being a religious outsider? By definition, religion is something that “binds,” you write, and you conclude that it doesn’t just “come to those who wait.” Other than the bonds of motherhood, after the last few years of “vagabonding” across America’s landscape of faith, what binds you religiously, spiritually?

In one sense, yes, I still feel like a religious outsider in that I am not a card-carrying member of a religious institution. I have not taken religious vows; I have not sought refuge in the teachings of the Buddha; I have not “reunited” with “my” guru; I have not been saved in any formal sense. And yet, I feel a familiarity with the religions I was exposed to; I now feel comfortable in just about any house of worship.

Surrendering one’s self to God or to a Higher Power, worshipping the Goddess, or bowing to the Buddha — these have all been demystified and humanized for me. I no longer look at people who wear robes and habits, or who live in a communal setting, or who don a turban or shave their heads, or who walk door-to-door in the blazing sun with books in hand and wonder, “Why in the world would someone give up their life to do that?” Researching and writing this book has given me a better understanding of the reasons people sacrifice certain “American” freedoms in exchange for certain spiritual freedoms. I’ve come to see that we’re all surrendering ourselves to one thing or another: our jobs, our ambitions, our car payments, our children, our insecurities, our secrets. When I saw firsthand the beauty and peace that faith brings to many peoples’ lives, particularly through the cumulative effect of practice, my outsider status shifted a few degrees.

I’ve always considered myself to be a person of faith, though I’ve never had formal structure or guidance. I’ve met a number of religious people of every creed who consider my perspective and approach to be illegitimate, or at least misguided and incomplete; a lot of people actually expressed pity for me and what they saw as my lack of clarity, as in I hadn’t yet seen their light. But that’s why faith is so personal; no one else can evaluate or quantify it for you.

I think religious “outsiders” are common in America because in this country we are caught between our need to be individuals and our desire to be part of something larger than just ourselves; it is a conflict innate in freedom. Many of us are wary of anything we perceive as constraining or controlling. And because many of us do not live in the same city or state or even country as our parents and close relatives, we’re fractured, and that carries over into the religious traditions our ancestors assumed we’d willingly inherit. Overall, we just don’t have the kind of cohesiveness and continuity that fosters multi-generational faith, the kind that’s imbedded. That said, I am now less wary of organized religious expression than before I wrote IN SEARCH OF GRACE, though I remain cautious about group-think. I hope someday to walk into a sanctuary and realize, “Ahh, I’m home.” But, so far, the only place that makes me feel that way is my own little home where I live with my son and husband. Besides feeling spiritually challenged and expanded by them, I am occasionally ventilated by my vinyasa (Hatha) yoga classes, which remind me, above all, to breathe and get out of my own way!