Companion in Exile

Read an excerpt from University of Notre Dame theology professor Timothy Matovina’s essay on devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe at San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, Texas. It appears in HORIZONS OF THE SACRED: MEXICAN TRADITIONS IN U.S. CATHOLICISM, edited by Timothy Matovina and Gary Riebe-Estrella, SVD (Cornell University Press).

As Mexican immigrants streamed into San Antonio during the first decades of the twentieth century, their conviction that Guadalupe had elected the Mexican people as her “chosen race” contrasted sharply with the experience of Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent), who were relegated to secondary status during U.S. territorial expansion. According to one writer in La Prensa, the most prominent Spanish-language newspaper in San Antonio, although Mexicans born in the United States might be “enmeshed in the contradictory intermingling of Anglo-Saxon education and Latino thought, and consequently lose touch with their ancestral heritage, in spirit they remained Mexican because they had not forgotten how to pray in Spanish and worship the Virgin of Guadalupe.” The immigrants’ esteem for their heritage and confidence in their dignity as Guadalupe’s favored daughters and sons provided an impetus for Mexican Americans to renew their own ethnic pride and sense of dignity as the children of a heavenly mother. In an era of rising ethnic prejudice in San Antonio, Mexican emigres’ assurance of their celestial election and rich cultural patrimony fortified both Mexicans Americans and the immigrants in their resistance to discrimination.

As Mexican immigrants streamed into San Antonio during the first decades of the twentieth century, their conviction that Guadalupe had elected the Mexican people as her “chosen race” contrasted sharply with the experience of Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent), who were relegated to secondary status during U.S. territorial expansion. According to one writer in La Prensa, the most prominent Spanish-language newspaper in San Antonio, although Mexicans born in the United States might be “enmeshed in the contradictory intermingling of Anglo-Saxon education and Latino thought, and consequently lose touch with their ancestral heritage, in spirit they remained Mexican because they had not forgotten how to pray in Spanish and worship the Virgin of Guadalupe.” The immigrants’ esteem for their heritage and confidence in their dignity as Guadalupe’s favored daughters and sons provided an impetus for Mexican Americans to renew their own ethnic pride and sense of dignity as the children of a heavenly mother. In an era of rising ethnic prejudice in San Antonio, Mexican emigres’ assurance of their celestial election and rich cultural patrimony fortified both Mexicans Americans and the immigrants in their resistance to discrimination.

San Fernando’s Guadalupe celebrations engendered a sacred realm in which cathedral congregants were valued and respected, symbolically reversing the racism they encountered in the world around them. While Mexican-descent residents continued to struggle for equal rights in schools, courtrooms, and the work place, at San Fernando they instilled in one another a sense of dignity and pride as children of a loving mother. While racism in movies and other areas of social life was so strident that even Spanish-language newspapers advertised “whitening” cream, Mexican-descent devotees acclaimed “la morenita,” the brown-skinned celestial guardian, displayed her image in public processions, and enshrined the image prominently in the cathedral. While their representation on government bodies like the city council was minimal, San Fernando congregants exercised leadership in their many pious societies, organizing communal events like the annual Guadalupe triduum and processions.

While the Spanish language was officially banned in public schools, Guadalupan devotees marched through the city plazas and streets singing the praises of their patroness in their native tongue. While the threat of repatriation hovered ominously, especially during the Depression, familiar devotions like those to Guadalupe made San Fernando a spiritual home that provided solace and reassurance. While frequently rebuffed at Anglo-American parishes, San Fernando congregants celebrated their patroness’s feast in the company of archbishops, bishops and priests whose presence confirmed the value of their language, cultural heritage and religious traditions.

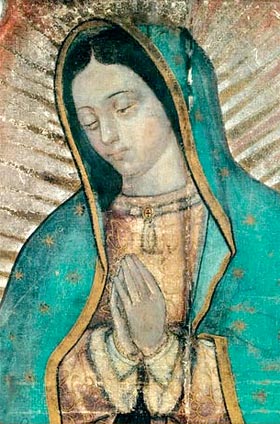

Consciously or not, San Fernando’s Guadalupe rituals counteracted the hostility and rejection that parishioners often met in the wider church and society. As one devotee remarked in acclaiming Guadalupe’s compassion for the poor and downtrodden: “Because the Virgin is Indian and brown-skinned and wanted to be born in the asperity of [Juan Diego’s] rough cloak — just like Christ wanted to be born in the humility of a stable — she is identified with a suffering, mocked, deceived, victimized people.” Another enthusiast wrote that “la morenita” was nothing less than a symbol of our race and contended that “if it had been a Virgin with blue eyes and blonde hair that appeared to Juan Diego, it is possible that she would have received a fervent devotion, but never as intense, as intimate, nor as trusting as that which the multitudes offer at the feet of the miraculous Gudalupita.”

The primary basis of Guadalupan devotion for many Mexican-descent residents was their steadfast conviction that Guadalupe “continues to perform miracles.” Their fervent appeals for Guadalupe’s celestial aid led local clergy to denounce some forms of devotion as superstitious, such as the praying of forty-six rosaries for the forty-six stars on Our Lady of Guadalupe’s mantle. Nonetheless, advertisements in local Spanish-language newspapers appealed to devotees’ strong faith in Guadalupe as a protectress and healer. One ad for “Te Guadalupano Purgante” (Guadalupe Purgative Tea) described Guadalupe as the “queen of the infirmed,” extolling the powers of this tea made from the “herbs, flowers, tree bark, seeds [and] leaves… that grow in the environs of Tepeyac, where Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared.”

Guadalupan devotion at San Fernando was far more than an expression of Marian devotion. It encompassed patriotism and political protest, divine retribution and convenant renewal, ethnic solidarity and the resistance of a victimized people, spiritual reconquest and reinforcement of social hierarchy, a model of feminine virginity and domesticity and an inspiration for women to be active in the public arena and demand equality, a plea for miraculous intervention and an inducement for greater participation in the church’s sacramental life. Despite attempts to engage Guadalupan devotion as a justification for existing social relations, at San Fernando Guadalupe commemorations also provided a ritual arena for Mexicans and Mexican Americans to forge and celebrate an alternative world, one in which painful realities like exile and racism could be redefined and reimagined.

A brown-skinned “exile” herself, Guadalupe was a treasured companion whose faithful encountered her most intensely in the midst of the displacement, discrimination, degradation and other difficulties they endured. Fortified by her presence, these faithful confronted their plight by symbolically proclaiming in Guadalupan devotion that exiles were the “true” Mexicans, that despised Mexican-descent residents were a chosen people, and that devotees of “la morenita” were heirs to the dignity she personified.