Somali Muslims in Maine

LUCKY SEVERSON, guest anchor: They first arrived in the U.S. in the mid-’90s, mostly Georgia and Tennessee — Muslim immigrants from war-torn Somalia, searching for a little peace and happiness. But they were alarmed at what they felt was an environment too promiscuous and too violent for their children. So they went on a search for a smaller, safer place to raise their families, and about a thousand ended up in Lewiston, Maine. And in Lewiston, they may have found more or less than they bargained for.

We were curious about the moral obligations and dilemmas facing communities, facing new immigrants.

Hardly a scene you’d expect to find in what is arguably the whitest state in the union.

But at the Lewiston Adult Education Center, English as a second language classes are busting at the seams with students “from away,” as Mainers like to say. In this case, from Somalia, way way away.

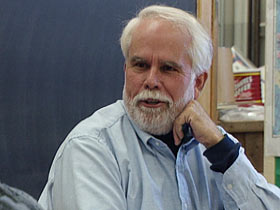

JIM BENNETT (City Administrator): Two years ago, we had about 50 students in our school system that had requirements of English as a second language. Today we are 250 to 300.

SEVERSON: Jim Bennett, the besieged city administrator. Two years ago, there wasn’t one solitary Somali in all of Lewiston. Now there are over a thousand, in a town of only thirty-five thousand. Like many immigrants, they like to stick together.

MUHAMMAD (Somali immigrant): We’re family. So we don’t want to be lonely here. So we are in a group, which, we don’t see anything wrong with that.

STORE OWNER: You know this meat is camel.

SEVERSON: It’s not that this camel meat troubles some Lewistonians. It’s because so many Somalis came so suddenly, taxing city services, taking scarce jobs, and driving up the rent.

(to Mr. McLeod): You say you lost an apartment to a Somali?

SCOTTY MCLEOD (Lewiston resident): Yes, the landlord thought their money was better than mine.

SEVERSON: We couldn’t verify Scotty’s story, but there were others. This is Desiree Leddington.

DESIREE LEDDINGTON (Lewiston resident): I kinda feel the city could do a little more for us who were here first, because I am almost eight months pregnant, and I am living in a one-bedroom apartment with two other people that are expecting any day. Because there just isn’t any housing, most of it is going to the Somalis.

SEVERSON: Vicky Camire, proprietor of Vicky’s Market, says she’s noticed tensions rising since the Somalis started arriving.

VICKY CAMIRE (Lewiston resident): There is a lot of talk that they are getting more benefits than the average American person. Not being racist or anything — I am not prejudiced in any way. I just feel that there are too many Americans that are poor, that are homeless, that are disabled. They need the help first.

SEVERSON: Truth is, the Somalis aren’t getting any more benefits than ordinary Lewistonians. Those are just rumors. It’s also not true that the government gives them $10,000 cash to buy new cars.

UNIDENTIFIED SOMALI: I buy the car, it’s not welfare, honest.

SEVERSON: Mark Schlotterbeck, a missionary at the Calvary United Methodist Church, says there were some wild ideas flying around.

MARK SCHLOTTERBECK (Missionary, Calvary United Methodist Church): I think people were afraid of their life changing, life as they knew it changing. People came who were dressed differently, who were strong in another way of faith, who looked different.

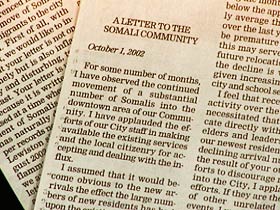

SEVERSON: There were so many rumors and stories and Somalis that Mayor Raymond wrote an open letter saying the city was “overwhelmed” and asking Somalis to stop coming and “exercise discipline.” It wasn’t a mean letter, but it drew so much national attention, the mayor virtually disappeared and stopped talking to the national press.

Mr. BENNETT: I think we could have done maybe a different way of trying to address the issue, so it didn’t become a national spotlight.

SEVERSON: The Somalis say the letter only made matters worse.

DIREIYE AHMED (Somali immigrant): After the letter, it seems people, like if I drive down the street, people are going to make signs like I am some kind of animal or something. I am just a man, just like anybody else.

MUHAMMAD: So it’s very hard. It’s very hard. Is it harder after the letter? Yes, it is very hard because some of them, not the intellectual ones, they look at us in a funny way.

SEVERSON: Harvard expert on immigration Mary Waters says Lewiston’s reaction is not that unusual.

Professor MARY WATERS (Harvard University): You can find backlashes against European immigrants, and Italians, Irish, Polish, and Jews. Throughout our history there have been cases in which immigrants have been the object of a lot of dislike and distrust and actual violence against them. So it is expected what happened in Lewiston, I think.

SEVERSON: History has repeated itself more than once in Lewiston. The first major immigrant group to face a hostile reception were the Irish canal diggers in the 1850s.

Prof. WATERS: When they came in they were poor, they were very different, and they were seen as being very threatening and so there was violence — burning of churches.

SEVERSON: And then the French Canadians arrived at the old train station. They got the cold shoulder even as they made Lewiston prosper, working in the textile mills and shoe factories that are now vacant.

Prof. WATERS: They were forbidden to speak French in school. They were last chosen to be hired. A lot of prejudice against both those groups.

SEVERSON: But those immigrants were European and white, and they ultimately achieved the American dream. Professor Waters worries that it will be more difficult for the Somalis, even though they are admired for their ambition.

Prof. WATERS: There still is a lot of racial prejudice against African Americans and black immigrants, and so an open question is how welcoming we will be and how accepting we will be of the Somalis.

SEVERSON: But there have been times in Lewiston’s past when the city was uniquely open-minded. In 1965, for instance, in this very building, when Muhammad Ali knocked out Sonny Liston in the first round. Many cities refused to host the fight, protesting the fact that Cassius Clay had just become a Muslim, a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, and changed his name to Muhammad.

RODA ABDI (Somali immigrant): The number one thing we like about America is, like, you can practice your religion.

SEVERSON: Roda Abdi operates a market in Lewiston. As with all Somalis, religion is extremely important. The immigrants have already installed a temporary mosque in downtown Lewiston. It was Islam that kept them going after they fled a brutal civil war at home in the early 1990s, lived in refugee camps in Africa, and finally, five years ago, landed in the U.S., many near Atlanta — determined but still unable to find happiness.

The Somalis didn’t like the big-city environment, what they perceived as bad influences on their children. So they went looking for a smaller place, a safer place to call home, and raise their families. Some of them ended up here.

Prof. WATERS: I think we have a moral obligation based on the values that we hold of being a refuge for people who are fleeing persecution. The nation as a whole has decided to let the Somalis in and has given them assistance and has brought them in. It is really Lewiston that’s taking care of them and educating their kids and housing them and finding them jobs. In some sense they are doing the work of the nation by absorbing these immigrants that we let in, and it is hitting them.

SEVERSON: The Somalis’ timing could have been better. They were up against not only old prejudices but some new and extraordinary circumstances as well.

Mr. BENNETT: There were so many other uncertainties and pressures that were going on that have nothing to do with their decision to make our city their homes. If the economy was a little better and we weren’t getting ready to go to war, and, you know, maybe the BLACK HAWK DOWN movie didn’t come out.

SEVERSON: He says, and others agree, that the movie BLACK HAWK DOWN, one of this year’s most popular, adversely affected attitudes against Somalis. The movie was based, from the American viewpoint, on a U.S. raid gone terribly wrong in 1993. Nineteen American soldiers and many Somalis were killed in a fierce gun battle in the capital, Mogadishu.

It turns out that a local boy, Staff Sargent Thomas Field, was killed in that battle.

Mrs. ABDI: That movie didn’t help. I feel sorry what happened and I, you know, have sympathy for the family, but we don’t have to forget, my whole family killed in that war.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: A lot of people ask me, “Where you from?” and I say, “Somalia,” and they say, “Where is Somalia?”

MUHAMMAD: They don’t know the difference — Middle East and Somalia — that’s the problem. We’re an African continent. We’re not Israel. We’re not Iraq. We are not Egypt. We are Africa.

SEVERSON: And there’s another factor that has affected attitudes in every city in America.

Ms. CAMIRE: I think September 11 has put fear in the hearts of every American. I think that there is tension all over the country right now, and this fear that every time you see someone who’s of another country or a culture you wonder, are they going to shoot me?

SEVERSON: After the mayor’s letter, a public show of support and welcome signs that feelings are on the mend, but still a ways to go.

Mr. SCHLOTTERBECK: What does it mean? I think it means that we have lots to work out. But potentially a tremendous increase in who we are as a community.

SEVERSON: Take away the rumors and the misunderstandings, and Lewiston is not much different from any other American town. People struggling to make a living. After the dust settles, they’re hoping to make a community.

Word now that the government plans to resettle 10,000 more Somalis across the U.S. next spring. Last month Holyoke, Massachusetts voted to reject 300 Somali refugees even though it could cost local agencies a million dollars in federal grants. A spokesman for the Federal Office of Refugee Resettlement said he has never known a community to reject refugees. In reality, the vote was purely symbolic — a community cannot legally keep immigrants from moving in.