In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

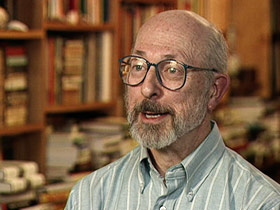

Peter Steinfels

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, a Catholic writer and his new book on what he calls the crisis in the U.S. Catholic Church, a crisis that goes well beyond the sex abuse scandal. The book is A PEOPLE ADRIFT, and the author is Peter Steinfels, a lifelong Catholic who says the church he loves, the largest church in the U.S., the church of one American in four, is “on the verge of either an irreversible decline or a thoroughgoing transformation.”

We spent a recent Sunday with Steinfels and his wife, Margaret, beginning with their walk to mass at New York’s Church of the Ascension.

Steinfels fears that unless American Catholics overcome what he calls a “vacuum of leadership,” they will experience “a soft slide” into Catholicism in name only, as has happened in much of Europe.

PETER STEINFELS: The danger is a kind of hollowing out of the faith of Catholics, where it no longer will affect the central decisions that they make.

ABERNETHY: U.S. bishops have often been what he calls “disgracefully slow” to respond to problems. Steinfels charges that the bishops are too timid, too subservient to the Vatican.

Mr. STEINFELS: Again and again, they have tended to look over their shoulder toward Rome and the Vatican rather than look right in front of their faces to what was happening in the Church.

ABERNETHY: Steinfels is a religion columnist for THE NEW YORK TIMES, where he had been the senior religion reporter. Earlier, he was the editor of the liberal, lay Catholic magazine COMMONWEAL, and so, later, was his wife.

Steinfels is also a historian, who says some of the Church’s conflicts began with changes in the world around it — ideas about human sexuality, for instance, and the equality of women.

Other problems, he says, grew from decisions by the Church itself, such as those coming out of the Second Vatican Council in the early ’60s.

Mr. STEINFELS: The very fact that the priest is facing the people from the other side of the altar, that the Mass is said in English, that the congregation is participating much more fully, both in responding to the priest and in song.

ABERNETHY: Each change, says Steinfels, helped polarize the Church, liberals against conservatives.

Steinfels says some Vatican teachings have been contradictory, and that has caused problems. For instance, the Church has strongly affirmed the equality of men and women. But it also says only men can be priests, and many women resent that.

Mr. STEINFELS: The truth is that unless women can be put into visible, ritual roles and have a real decision-making role within the Catholic Church, this conflict is just going to be something that really undermines the Church’s credibility.

ABERNETHY: Perhaps the greatest challenge to Vatican credibility came after Pope Paul VI’s 1968 refusal to permit artificial birth control. By big margins, American Catholics simply ignored the pope’s teaching, and that weakened Vatican authority across the board.

Also, the Church teaches that marriage and raising a family is a holy calling just like the celibate priesthood. But Steinfels says that helped trigger the priest shortage because many men who had been ordained, or were thinking about it, felt they could be just as holy if they got married.

Mr. STEINFELS: There was one priest for about 650 Catholics in 1950. Today there may be one priest for perhaps 1,400.

ABERNETHY: That decline meant that jobs once done by priests were taken over by laymen and, mostly, laywomen. There are now 30,000 Catholic lay ministers, more than the 27,000 active priests in the dioceses. Steinfels says the Church has not yet adjusted to that new lay leadership.

Sunday brunch at the Steinfels’ now includes three generations, among them two new grandsons.

Afterwards, we talked with Steinfels about the Church’s future. He does not deny that the Vatican helped cause many of the U.S. Church’s problems. But he does not blame the Vatican explicitly because, he says, he does not want American Catholics to think there are no changes they can make.

Mr. STEINFELS: What I am concerned about is that people not just wait upon the bishops, or wait upon a new pope or a change in the Vatican — that there is a lot that can be done by laypeople independently.

ABERNETHY: Americans could think through such practical issues as the costs of having married priests with families to support. Lay Catholics could improve the quality of Catholic colleges and hospitals, and of Sunday masses and religious education. He also thinks Americans could press the Vatican to let women be ordained deacons. And the ordination of women priests?

Mr. STEINFELS: I grew up in a family that always wanted to have the Mass said in English instead of Latin. I never expected to see that. I did see it. So when it comes to the question of ordination of women, I don’t know. I may see it.

ABERNETHY: Steinfels is doing a lot of speaking these days, recently at a panel at Boston College.

Mr. TIM RUSSERT: Where do you see the Church at the end of the 21st century?

Mr. STEINFELS: My hope is that we can build and strengthen the kind of infrastructure that will be the platform and the vehicle for the work of grace and the individual heroism. And if we can set that in place, maybe a lot of the 21st century will take care of itself.

ABERNETHY: One remarkable change Steinfels thinks is possible: if Catholic women could be ordained deacons, he says — even if they are not priests or bishops — they might be eligible to be appointed cardinals, and help elect future popes.