In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Operation Whitecoat

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, the story of a group of American soldiers — conscientious objectors — who volunteered to expose themselves to deadly viruses and bacteria, rather than go to war. They were Seventh-day Adventists. Over a 20-year period, beginning in the 1950s, the army used them to test vaccines against biological weapons. Today they look back on their experience, most of them with no regrets. Lucky Severson reports.

KENNETH JONES: My name is Kenneth Jones and I’m from Riverside, California.

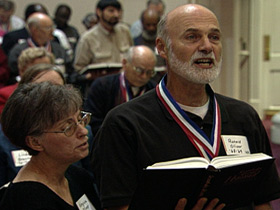

LUCKY SEVERSON: Overall they numbered about 2,300, young men then, veterans of the U.S. Army’s top secret “Operation Whitecoat.” This is their 30th-year reunion, for most a celebration of pride in the sacrifices they made for their country. These were unusual soldiers, to say the least. They were all members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and they never fought in any battlefield. Their mission was to serve as human guinea pigs.

Most Whitecoats fought their war at Fort Detrick, Maryland. The enemies were dangerous and deadly viruses and bacteria, administered by their own government. The purpose of the program was to help develop and test vaccines. Wendell Cole was exposed to the dangerous virus called Q fever.

(to Wendell Cole): Are you proud of participating?

WENDELL COLE (served 1954-56): Yeah, and when I check out I’m going to have an American flag, a military funeral, and all of those other things they want to give you. I’m proud.

SEVERSON: Operation Whitecoat began in 1954 in the early years of the Cold War. The fear then was that Russia was ahead in the development of biological warfare. The U.S. was struggling to catch up, using rats and monkeys, but animal responses do not always reflect those of humans. That’s when the army approached leaders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, whose members are called to adhere to a strict health code, no drinking or smoking, and take the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” quite literally. The church has always been engaged in medical missionary work and draws inspiration from the quote in the book of James — “If you know to do good and you don’t do it, that is wrong.”

Chaplain RICHARD STENBAKKEN (Adventist Chaplaincy Ministries): There seemed to be a natural fit, so when the military came to the church — “We are drafting a bunch of your guys; most of them are going into the medics; most of them are noncombatants. There is this ethos and ethic; it seems like a good test group.”

SEVERSON: Richard Stenbakken was an army chaplain for almost 24 years, and is now director of the church’s chaplain ministries throughout the world. He says the church approved the plan because it was mutually beneficial, and allowed members to worship on Saturday, their Sabbath.

Chaplain STENBAKKEN: Sabbaths were free; they were making a contribution to humanity; they were in a nonkilling situation; it seemed to be, and, I think, was a very good fit.

SEVERSON: There was a troubling ethical question the church had to come to grips with about members participating in tests that could be used for offensive weapons.

Chaplain STENBAKKEN: If the Seventh-day Adventist Church felt there was any clear evidence that this material the Whitecoats were involved with were being used offensively, I think the church would have counseled its men from going into it. Could some of that data be used ultimately in another way? I can’t answer that other than to say data is data, and how people use that data is their responsibility.

SEVERSON: There was one other unusual aspect to Operation Whitecoat. The volunteers were informed about the risks involved and required to sign a consent form. They could also leave the program whenever they wanted. And hardly anyone left, even those faced with exposure to the deadly tularemia bacterial, like Ed Lamb, who has no regrets.

ED LAMB (served 1963-65): They briefed us so thoroughly, they were really careful about the preparation, and we sat through meetings and they were spelled out in detail. And I really had no qualms about it.

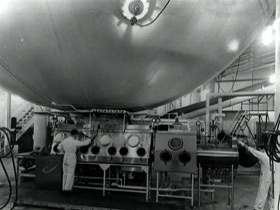

KEN JONES (served 1954-56): I was the first Whitecoat to arrive in Fort Detrick and go through the Eight Ball. I’m proud of that opportunity.

SEVERSON: This 40-foot-high steel sphere was the central experiment of the Whitecoat project. It was called the Eight Ball. Here’s what would happen: scientists would fill the Eight Ball with dangerous viruses or bacteria aerosol. Volunteers wearing gas masks would hook up to the Eight Ball and breathe in the infected air.

The Whitecoaters have much to be grateful for. None died, at least not during the testing period, which began in 1954 and ended in 1973. What happened after is unclear, although the military recently sent out questionnaires to 1,000 volunteers, and received responses from 522. This is Colonel Phillip Pittman.

Colonel PHILLIP PITTMAN (USAMRIID, Fort Detrick): We found that for the most part, there was no — we could find no adverse health effect from their participating in biomedical research.

SEVERSON: Colonel Pittman says the study did find an increase in the incidence of asthma and headaches among some volunteers. But it was a very limited study. Only 25 percent of the Whitecoaters were surveyed, partly because the army and the church have lost track of hundreds of volunteers. The military chose not to fund blood tests, which could have been far more definitive.

Col. PITTMAN: A pitfall is we do not know of all of the volunteers who have subsequently died and thus we don’t know what they died from, so we cannot evaluate death and the cause of death.

SEVERSON: The survey apparently missed Gene Crosby, who can’t get around without his wife Rhonda.

GENE CROSBY (served 1964-66): I asked him, Major Dangerfield, when I drank that stuff, was it going to last any longer than two weeks? “Oh no, got the antidote, it will be all over in two weeks,” and it isn’t over yet today.

SEVERSON: Crosby served 1964 to 1966. He’s had two heart attacks, a stroke, and several other serious health problems. He has an autoimmune disease called ankylosing spondylitis.

RHONDA CROSBY: His brother was already a medic in Germany, letting him know that if you are going to be a medic, you are going to jump out of a helicopter and be shot at, that[‘s] what the Viet Cong are shooting at. What would you [do,] take a chance to be stateside and be alive or go jump out of a helicopter and be dead? Gene took the chance to stay alive. Gene is wishing now that he took the chance on the helicopter.

SEVERSON: He was told three years ago that he would be dead within a year. But he’s still fighting, this time against the army, which he says has stonewalled his pleas for help. The couple has also left the Seventh-day Adventists, saying the church sold them out. Chaplain Stenbakken said he was unfamiliar with the Crosby case.

Chaplain STENBAKKEN: There’s always the dangerous possibility of something going awry.

SEVERSON (to Chaplain Stenbakken): Do you think it would be the church’s ethical responsibility to help him out?

Chaplain STENBAKKEN: The responsibility is a shared responsibility.

SEVERSON: Almost everyone we spoke with is proud of their military service, although there were some who questioned the long-term medical and psychological support they received from both the army and the church.

LESTER BARTHOLOMEW: They volunteered us; this was a bunch of Seventh-day Adventist kids.

SEVERSON: Lester Bartholomew and Jerald Lea both served between 1965 and 1967.

(to Mr. Bartholomew): What kind of tests did you have?

Mr. BARTHOLOMEW: I had rabbit fever, black plague, and tularemia.

JERALD LEA: His temperature was up to 106 and we had him in ice to get his temperature down. He didn’t remember most of it.

SEVERSON: And Lester says he’s had some lingering effects, though nothing serious.

Mr. BARTHOLOMEW: That’s what I’m negative on. Seventh-day Adventists probably had one of the biggest medical organizations in the world at that time, and there was not backup before we went in and no backup after we went in, and the army denies that we did anything when we were there.

SEVERSON: But the overwhelming sentiment here is that the testing, their sacrifices, made the U.S. a safer place. We now have inoculations against many of the diseases and viruses tested here. We have much more effective protective gear, and a model of how to conduct human experiments with informed consent.

Chaplain STENBAKKEN (Addressing Group): It is the soldier, not the reporter who has given us the freedom of press. It’s the soldier, not the poet who has given us freedom of speech. It is the Whitecoats who have given so much that we have health and safety and freedom.

ALLAN WOLFSON (served 1964-65): Thanks to the Lord, I’m alive and glad to be part of the Whitecoats, and I would do it all over again.

SEVERSON: It’s been 30 years since the testing ended. And it’s unlikely it will ever be repeated. But if there were a dire national emergency, it seems that most of these men would be proud to volunteer all over again.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Lucky Severson.