Illegal Immigration

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, illegal immigrants. There are more than eight million of them in this country. And while there is a lot of discussion about controlling U.S. borders and enforcing the laws, there are also those who say these immigrants are often exploited, and denied basic rights. Are they a drain on the economy — or poor people deserving compassion? Saul Gonzalez reports from Los Angeles.

SAUL GONZALEZ: At dawn in Los Angeles, these men are looking for work at a day laborer site established by the city of Los Angeles and the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights.

Undocumented Worker #1 (Through Translator): From my perspective, there’s money in Los Angeles, but we’re finding that there’s few jobs. Of the little work I’ve found, I’ve sent the money to my family back home.

GONZALEZ: The national debate over illegal immigration is often framed in economic terms, such as whether undocumented workers contribute more to the economy then they take out, and whether they take jobs away from U.S. citizens. However, illegal immigration also forces America to confront a profound ethical question, namely, how does the country reconcile treating poor and vulnerable newcomers compassionately, while defending its immigration laws and national self-interest?

Immigrant rights advocates say undocumented workers often fall prey to unscrupulous employers.

ANGELICA SALAS (Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights, Los Angeles): We have a fundamental belief that an individual has inalienable human rights and that those rights are not diminished once they cross a border. There is a belief by the general populace that the undocumented do not have rights. So because of that situation you have employers who are more than willing to pay individuals less than minimum wage, but unfortunately we see people who are not paid at all.

GONZALEZ: Ira Mehlman, with the Federation for American Immigration Reform, says the U.S. needs to be more concerned about upholding its immigration laws than protecting undocumented workers.

IRA MEHLMAN (Federation for American Immigration Reform): The United States has an obligation to enforce the laws of this country — all the laws of this country — not just the ones that people want to obey. Why should anybody obey our immigration laws when there’s clear evidence that if you come here illegally, nobody is going to do anything about it? And, in fact, you’re going to have advocates here who are going to say, “Let’s legalize these people once they get here, let’s reward them for having broken the law.”

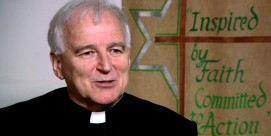

GONZALEZ: Some people of faith believe the country needs to show immigrants hospitality, even those who are here illegally.

RABBI MARC DWORKIN (Leo Baeck Temple): The first thing we have to do is not to deny people basic human and civil rights. So I would say this concept of welcoming, of hospitality even, certainly not exploitation of the stranger, is very essential to religious thought.

VICTOR DAVIS HANSON (Author, MEXIFORNIA): You and I welcome people into our home. Do we welcome 500 people into our home? It’s a question of the limitations of time and space.

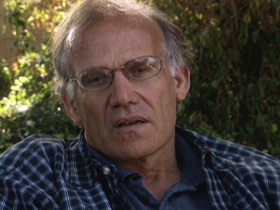

GONZALEZ: Victor Davis Hanson is a fifth-generation California grower, an author and social commentator. He says lax enforcement of immigration laws has permitted more people to come in than the United States can assimilate.

Mr. HANSON: The American tradition is that the immigrants come legally, they go through English immersion, a cultural immersion, and the second generation is clearly better off than the first. For so many people who come here so quickly and without knowing English, and illegally, we’ve overwhelmed the powers that we used to rely on to assimilate.

GONZALEZ: Hanson lives in California’s agricultural heartland, the San Joaquin Valley, a region whose economy benefits from undocumented workers like Geraldo Reyes.

GERALDO REYES (Undocumented Worker, Through Translator): We pick all the crops. And immigrants that are documented, you don’t see them here in the fields working, inhaling dirt. They think we’re bad, but without us, who is going to do it?

GONZALEZ: Hanson, who advocates stricter border enforcement, says those who favor relaxing immigration laws fail to recognize the moral consequences of their position.

Mr. HANSON: They are the immoralists, so to speak, because they depend on cheap labor to do what they do not want to do. They’ve allowed apartheid communities to spring up in California where the people who cut their lawns, clean their pools, paint their house are here illegally from Mexico, and yet their own children will never go to school with those kids, they’ll never shop at the same store, they’ll never wonder where they work. It’s almost as if they come in from Mars, parachute down, work eight hours, then out of sight, out of mind.

GONZALEZ: Illegal immigrants themselves are becoming increasingly vocal. In October, thousands converged on New York demanding legal status and safer workplace conditions. In Congress, legislators are once again considering bills long sidelined by the 9/11 attacks that would grant guest worker visas to hundreds of thousands of people now in the United States illegally. Immigrant rights advocates say such benefits are long overdue, considering what undocumented workers contribute to the nation’s economy.

Ms. SALAS: It is morally suspect when you’re receiving the work of all immigrants, that you really do benefit from cheaper products and just overall the service that immigrants give, but then not to see these individuals as humans, not to see them as people with families, with needs, with aspirations, hopes and dreams. That is incorrect.

Mr. MEHLMAN: The social costs of illegal immigration are enormous. It’s estimated that it costs about $7.5 billion in the U.S. every year to educate illegal alien children in our public schools. And so we are taking enormous resources that could be used to provide a higher quality of education for a lot of other kids in this country and spending it on illegal immigrants.

GONZALEZ: Others would say these immigrants must be educated so they can be part of the work force of the future. As the national debate continues over the burdens and benefits of illegal immigration, some people of faith say that compassion should govern policy.

Rabbi DWORKIN: We talk first of all of civil rights in this country as a citizen. There are also such things as human rights. If a person is in your midst, they have an absolute right to health care. They have a right to have their children get an education. Again, we cannot punish the stranger, or the children of the stranger, because we don’t like what the parent did.

GONZALEZ: The morality of how we treat newcomers has long been a national challenge, one that becomes more and more acute as the number of people in the U.S. illegally continues to grow. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Saul Gonzalez in Los Angeles.