Interview: Studs Terkel

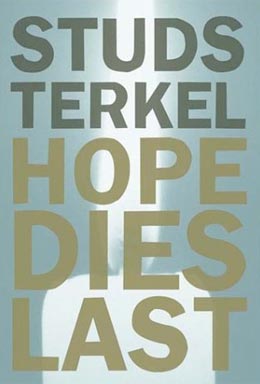

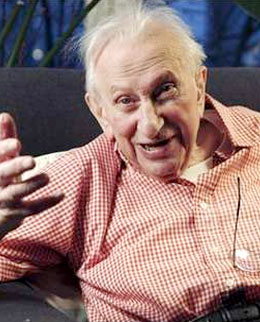

“Hope has never trickled down,” writes Studs Terkel. “It has always sprung up.” His most recent book, HOPE DIES LAST: KEEPING THE FAITH IN TROUBLED TIMES (The New Press), is an oral history of social action — a collection of interviews about faith and hope with workers, organizers, school teachers, immigrants, chaplains, cooks, custodians, priests, politicians, and pilgrims from one of America’s most thoughtful listeners:

Q: Is there a difference between hope and optimism?

A: Hope is more of a tightrope. You can hope and still feel guardedly so, even a little pessimistic: “I hope it will be better tomorrow than it is today.” We use the word “hope” perhaps more often than any other word in the vocabulary: “I hope it’s a nice day.” “Hopefully, you’re doing well.” “So how are things going along? Pretty good. Going to be good tomorrow? Hope so.” With optimism, you look upon the sunny side of things. People say, “Studs, you’re an optimist.” I never said I was an optimist. I have hope because what’s the alternative to hope? Despair? If you have despair, you might as well put your head in the oven.

“Hope dies last” was a phrase used by Jessie de la Cruz, one of the first women to work for Cesar Chavez in organizing the farm workers union. Very few women were involved in the beginning. She is one of the few. She said, “Whenever things are bleak and seem hopeless, we have a saying in Spanish: ‘La esperanza muere ultima.’ Hope dies last.” I thought, if ever there were a time [to write a book about hope], it’s now.

Q: What do you think September 11 has to do with this book and with what people told you?

A: I would have written this book anyway, I think, but September 11 italicized it. Even the book preceding this one [WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN? REFLECTIONS ON DEATH, REBIRTH, AND HUNGER FOR A FAITH], named after the old hymn that the Carter family and Johnny Cash sang, was about death. I wrote that one before September 11. But of course it wasn’t about death. No, it’s about life. The whole point is it’s about life itself. What’s the meaning of your death if there is no life to talk about? It was a hymn to life. And HOPE DIES LAST, you might say, is what follows.

Margaret Atwood, the Canadian writer, was talking about my previous books and how they all seem to deal with more visceral events, like the Great Depression, of which young kids know so little. It’s as though it never happened. Nonetheless, it was a visceral event…

Q: But hope is visceral too, isn’t it?

A: Yes. All the other books ask, “What’s it like?” What was World War II like for the young kid at Normandy, or what is work like for a woman having a job for the first time in her life? What’s it like to be black or white? Hope is more abstract but, at the same time, this turns out to be the most personal of all the books. This, in short, is a tribute to all those people whom I call “the prophetic minority.” Through history, there always have been certain kinds of people who had a hope. They did stuff they shouldn’t have done. They discommoded themselves. They could have led nice lives. HOPE DIES LAST is an anthem to people who have hope, who always have been kind of a minority, who are called “activists.” “Activist” means what? Someone who does an act. In a democratic society, you’re supposed to be an activist; that is, you participate. It could be a letter written to an editor. It could be fighting for stoplights on a certain corner where kids cross. And it could be something for peace, or for civil rights, or for human rights. But once you become active in something, something happens to you. You get excited and suddenly you realize you count.

HOPE DIES LAST is also a tribute to Virginia and Clifford Durr, two people who lived in the South and who were well-off. I dedicate the book to them because it is about all those who succeeded them. He was from a top family in Montgomery, Alabama. Her father was a clergyman. He was a member of the Federal Communications Commission under Franklin D. Roosevelt when World War II was going on. He’s the one who wrote that the airwaves belong to the public, and the public has the right to all variety of programs. Then came the Cold War and Joe McCarthy. President Truman said to Clifford Durr, “Your people have to sign a loyalty oath.” He said, “I don’t believe in it. I won’t. Under no circumstances will I allow my people to be demeaned by doing this.” And he resigned.

HOPE DIES LAST is also a tribute to Virginia and Clifford Durr, two people who lived in the South and who were well-off. I dedicate the book to them because it is about all those who succeeded them. He was from a top family in Montgomery, Alabama. Her father was a clergyman. He was a member of the Federal Communications Commission under Franklin D. Roosevelt when World War II was going on. He’s the one who wrote that the airwaves belong to the public, and the public has the right to all variety of programs. Then came the Cold War and Joe McCarthy. President Truman said to Clifford Durr, “Your people have to sign a loyalty oath.” He said, “I don’t believe in it. I won’t. Under no circumstances will I allow my people to be demeaned by doing this.” And he resigned.

And Virginia Durr — I first heard of her in 1944 at a big anti-poll tax gathering in Chicago. You know what the poll tax is? It was aimed primarily against blacks and poor whites. They couldn’t vote, especially African Americans in the South. So Virginia was campaigning against the poll tax in the company of Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, an eminent African-American educator. This big symphony hall in Chicago was jammed! Dr. Bethune was good, but Virginia Durr — this lanky forty-year-old white woman — set the house on fire. So I go backstage with a number of us to shake her hand. As I put forth my hand, she says, “Thank you, dear,” and she puts forth her hand. In her hand are a hundred leaflets. She says, “Now, dear, you hurry outside and you pass out those leaflets, because Dr. Bethune and I are due to speak at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in a couple of hours. Hurry, dear!”

Virginia and Cliff Durr were ostracized by their community. They suffered a great deal. They were under investigation by Senator James Eastland of Mississippi, who was very segregationist and very antiblack. He said the group the Durrs belonged to, the Southern Conference on Human Welfare, was subversive because it was antilynching, anti-poll tax, and for integration. The Durrs got themselves in big trouble. Virginia’s seamstress was a woman named Rosa Parks. She encouraged Rosa Parks to go to a school that was teaching organizers, the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, with Myles Horton, a great teacher. Rosa Parks went to school there and so did Dr. Martin Luther King and others. But the school was under attack. These people, few in number and way outnumbered, were fighting way back then. In the book I celebrate the ones who are doing this sort of work today.

Q: You interview a number of Catholic priests, or former priests, in this book. What did you learn from them about hope?

A: Religion obviously played a role in this book and the previous book, too. You happen to be talking to an agnostic. You know what an agnostic is? A cowardly atheist. Nonetheless, do I have respect for people who believe in the hereafter? Of course I do. I might add, perhaps even a touch of envy too, because of the solace. If solace is any sort of succor to someone, that is sufficient. I believe in the faith of people, whatever faith they may have.

It turns out that there are a great many Catholics in this book, like Kathy Kelly, a disciple of Dorothy Day. Kathy taught at a very wonderful parochial school, St. Ignatius, in Chicago. More on her later. We’ve got John Donahue [executive director for the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless]. He’s not a priest anymore and he is married. His story is about worker-priests, the phrase that was first used by some French priests. Pope John XXIII admired worker-priests — those who work in the community, work in the neighborhood. John Donahue tells the story of the priest in Panama who organized a cooperative of coffee pickers. Their coffee is so terrific that it’s being sold all over the world. It was a priest who did that. Then we’ve got two ex-seminarians — Jerry Brown, the mayor of Oakland, and Ed Chambers, who succeeded Saul Alinsky as a community organizer and who teaches how to organize. He was a disciple of Dorothy Day, too. Jerry Brown still believes in his Jesuit training. A number of them still believe in that.

There’s a priest at the very beginning of the book, Father Bob Oldershaw, and his brother, who is a neurosurgeon. I interviewed him about his experiences in the Vietnam War with soldiers he had treated and what he saw. But along comes his brother who said, “Why don’t you have the two of us talk and reminisce, and you ask provocative questions?”

Father Oldershaw had a parish. His altar boy, a Mexican kid, Mario Ramos, was part of a gang, and he shot Andrew Young, son of Steven and Maurine Young, a nice kid. It was a mistake, because he thought Andrew Young was a member of another gang. Here is Father Oldershaw: “That was my altar boy who did the killing. At first, I said to myself, No way! Then I started thinking about what made him do it, where he comes from. Then I had to go see the couple,” who are not members of his parish, but he was praying for them. It was pretty tough. Finally, he did see them and they got together. That couple, in a sense, have adopted as theirs the boy who killed their son. The one who arranged the whole thing was Bob Oldershaw himself. The kid has been in prison and is now rehabilitated. Throughout the book, you have this aspect of faith. [Read the related R & E story “Forgiveness” about the Young murder.]

Kathy Kelly heads a group called Voices of the Wilderness, a campaign to end economic sanctions against Iraq. These are people who bear witness, as Dorothy Day did. Dorothy Day got in trouble and was arrested many times. Why did she do this when she could lead a nice, easy life and mind her own business? Dorothy Day said — and I’m sure that Kathy Kelly would say the same thing — “I’m working toward a world in which it will be easier for people to behave decently.” Now, think about that: a world in which it will be easier for people to behave decently. Kathy Kelly has borne witness in Basra and Baghdad to the innocent victims of war. She’s been mentioned for the Nobel Peace Prize several times. She has shadowed some of the thousands of missile sites we have. Many people may not think they have seen any, but they have when they drive by one in the Midwest. It’s like a little hill, but it just ruins the corn country around it. Corn can’t be planted. One day Kathy Kelly cut through the barbed wire at one of the missile silos. There she was — all eighty-five pounds of her — on this missile site. She starts planting some corn next to it. Of course, she put up a sign. She wanted people in the passing cars to see the sign: “Beat your swords into plowshares and study war no more,” from Isaiah, the Old Testament prophet.

She called up the authorities to be arrested, because obviously she violated security. Here comes a big truck with machine guns and everything. The commander says, “Will the person on that site get off with your hands raised and kneel to be handcuffed.” And she does. Just then, a young soldier, a kid of about nineteen, comes off the truck toward her with a gun pointed at her head. He’s trembling, because here’s the enemy. It’s Kathy Kelly. He’s told she’s a terrorist. He’s trembling, but he’s got a gun on her head. She looks at the boy and says, “Do you know why I’m kneeling now? Do you know why I’m here?” He says, “Why, ma’am?” “Because I’m praying for the corn to grow.” Then she looks at him and senses he’s a country boy. She says, “Wouldn’t you like the corn to grow?” “Yes, ma’am.” “Will you pray with me for the corn to grow?” He says, “Yes, ma’am.” And he thought of a prayer for the corn to grow. Then the kid says — he’s still got the gun to her head — “Ma’am, are you thirsty?” “Oh, yes.” It was a broiling hot day. He puts his gun down (which I’m sure is a violation) and he opens his canteen and says, “Ma’am, will you lean your head back a little?” and he pours some of the water into her mouth.

The judge was kind, but she’s not going to recant or say she’s sorry and she’s never going to do it again. Of course not. She got a couple of years in the federal pen. But she saw that boy in court. He was supposed to testify and he was trembling, because he thought she might tell the story. She said no, she just winked at him, and then she said, “If he reads this book, I hope he’ll forgive me for telling you the story.” So that is Kathy Kelly. And there is faith. And there is hope.

Q: Do you have to be an idealist to have hope? Can you be a realist and still be hopeful?

Q: Do you have to be an idealist to have hope? Can you be a realist and still be hopeful?

A: I think it’s realistic to have hope. One can be a perverse idealist and say the easiest thing: “I despair. The world’s no good.” That’s a perverse idealist. It’s practical to hope, because the hope is for us to survive as a human species. That’s very realistic. Why are we born? We’re born eventually to die, of course. But what happens between the time we’re born and we die? We’re born to live. One is a realist if one hopes.

Q: How did you grow up in Chicago? What did you grow up believing?

A: My mother ran a rooming house. My family was Jewish but not religious. My mother went through the rituals; my father didn’t. He was a freethinker. What made me was the hotel where I was raised. My father died and my mother ran it. Before that, it was a rooming house. In that hotel, there were these guys arguing. There were the old-time union guys and there were nonunion guys. There were what we called Wobblies, the IWW, and the guys who were anti-them would say, “I Won’t Work, that’s what IWW means.” They argued. That’s what we’re missing. We’re missing argument. We’re missing debate. We’re missing colloquy. We’re missing all sorts of things. Instead, we’re accepting.

Today, more and more, because of the nature of the press and TV and radio, celebrityhood has taken over, and trivia takes over. Way back in 1916, Upton Sinclair wrote THE JUNGLE, a famous book about how terrible conditions were in the stockyards. He was called a muckraker — the phrase used for those who were investigative journalists. He also wrote a book called THE BRASS CHECK. In the early days the brass check was something that someone got at a brothel, a sporting house. When you paid the madam two dollars (this was before inflation), you would receive a brass check. The girl would be given the brass check. At the end of the day, she would cash in all her brass checks. In those days, she’d get half a dollar apiece. Upton Sinclair called the reporters back in those days “brass check” people because they were like the call girls in the brothel. They just followed orders. In a sense, we have a lot of that today. But we have other journalists, and they are the few who come through here and there.

I’ve always felt, in all my books, that there’s a deep decency in the American people and a native intelligence — providing they have the facts, providing they have the information. The September 11 assault was horrendous. But there’s another assault that’s taking place. It’s an assault upon our intelligence. It’s an assault upon our sense of decency as well as upon our faiths too, I believe. We are the most powerful nation in the world, but we’re not the only nation in the world. We are not the only people in the world. We are an important people, the wealthiest, the most powerful and, to a great extent, generous. But we are part of the world.

Q: You have seen a lot and lived through a lot. Are you less hopeful or more hopeful now? Are things any worse today than they’ve ever been?

A: That’s a hard question. I am hopeful. The most amazing thing is that there are so many groups. I don’t understand the Internet real well. I’m very bad technologically. I can’t drive a car. I fall off a bicycle. I goof up the tape recorder. I’m just learning to use an electric typewriter — that’s my big advance. I’m not up on the Internet, but I hear that is a democratic possibility. People can connect with each other. I think people are ready for something, but there is no leadership to offer it to them. People are ready to say, “Yes, we are part of a world.” People are ready to say, “Yes, we are ready for single-payer health insurance.” We are the only industrialized country in the world that does not have national health insurance. We are the richest in wealth and the poorest in health of all the industrial nations. So people are ready. I feel hopeful in that sense.

I feel a little worried because of the nature of technology. Technology works in two ways. I’m ninety-one years old, thanks to technology — a quintuple bypass. It was the skilled hands of a surgeon, but there were also all these medical advances and the machinery that helped me. At the same time, we have the technology of destruction since Hiroshima and beyond — technology that can destroy the world.

So here we are. We have a choice to make. I’m merely paraphrasing Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein. I always love to quote Albert Einstein because nobody dares contradict him. Einstein and Russell together issued a joint statement some time shortly after Hiroshima: “We have a chance right now to live in a new world with so many possibilities. With labor-saving devices, people can learn new ways of earning their living, new ways of following what they want to do. Or we can engage in mutual destruction.” They both spoke of that back in 1945. It’s more than half a century later, and what they said is even more italicized.

That’s why I wrote this book: to show how these people can imbue us with hope. I read somewhere that when a person takes part in community action, his health improves. Something happens to him or to her biologically. It’s like a tonic. When you become part of something, in some way you count. It could be a march; it could be a rally, even a brief one. You’re part of something, and you suddenly realize you count. To count is very important. People say, “I’m helpless.” Of course, if you’re alone. There are so many groups — environmental groups, other groups — but there is no one umbrella.

Q: What do you hope for?

A: I hope for peace and sanity — it’s the same thing. I want a language that speaks the truth. I want people to talk to one another no matter what their difference of opinion might be. I want, of course, peace, grace, and beauty.

How do you do that? You work for it. I want to praise activists through the years. The ones in the book are alive today. But I praise those of the past as well, to have them honored. And I hope that memory is valued — that we do not lose memory.