In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

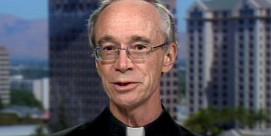

Randall Balmer Extended Interview

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview about evangelicals and evangelism with Randall Balmer, professor of American religion at Barnard College, Columbia University:

My sense is that evangelicals talk about doing evangelism a great deal more than they actually do it. I think one of the characteristics of being an evangelical is that you want to share your faith, or at least you feel you should share your faith or proselytize, bring others into the kingdom of heaven. And certainly that’s warranted in the New Testament. My sense, however, over the last 30, 40, even 50 years is that most evangelicals talk about doing that a great deal more than they actually do it. They tend to hire professionals to do it, so you have these large, particularly suburban churches, megachurches, or even churches that are not quite that large, who would have a visitation pastor or an evangelism pastor on their staff as a way of fulfilling that part of what it means to be an evangelical.

There’s not a whole lot of difference between proselytizing and evangelizing. I think that generally proselytizing has more of a pejorative connotation, and evangelicals talk about what they do as evangelism; they have evangelists, Billy Graham, Billy Sunday, a host of other evangelists who are active as full-time professional evangelists. They use the term “evangelism” more than “proselytization.” Besides, it’s easier to say.

I think evangelism’s always changing, and I think that’s the genius of evangelicalism throughout American history, is the way in which evangelicals have adapted to the cultural idiom, whatever that may be at any given time. In the 18th century you had George Whitefield coming with the Great Awakening, doing open-air preaching, very persuasive rhetoric; he [was] somebody who had been trained in the London theater and so he understood the importance of dramatic pauses and contemporary settings. He could bring tears to your eyes simply by saying “Mesopotamia,” he was that riveting a preacher. In the 19th century you had circuit riders; later in the 19th century you had coal porters who rode on the trading lines bringing gospel tracts and Bibles to western territories. In the 20th century you had the great urban revivalists, beginning with Billy Sunday and later with Billy Graham and so forth. So evangelicals are always crafting their message and using the media with extraordinary success in order to bring their message to the masses. I think what’s happened in the last 30, 40 years is that evangelicals have in many ways fine-tuned their message. The suburban megachurch, of course, is the great paradigm for evangelical adaptability to the larger culture, and learning how to speak the language of the suburban corporate culture in the case of Willow Creek, or speak the language of the hippie Jesus movement culture of the early 1970s with Calvary Chapel, and there are many other examples, but, again, evangelicalism has been masterful at adapting its message to the surrounding culture.

In the case of Willow Creek, they recognized that they were locating this new church, new in the mid-1970s, in a suburban context. So they speak the language of the corporate culture all around them. Willow Creek is often looked at as the great example of cultural adaptability. In the mid-1970s when Bill Hybels began the church, he did a door-to-door market research survey to find out why suburbanites were staying away from church. And then he proceeded to design a church in order to overcome their objections. He found, for example, they didn’t like religious symbols — no crosses, no icons — anywhere in the church. The building itself looks like a corporate office park or even a suburban shopping mall with a food court. Willow Creek is just one example of that, but evangelicals have been trying to adapt to the language and the idiom of the larger culture around them.

Evangelicals have probably been a little bit slower than others to pick up on the Internet, although more and more they’re catching up. Throughout American history, however, evangelicals have used communication technology quite effectively, beginning with radio in the early part of the 20th century and later with television and so forth. Aimee Semple McPherson was the first person to own a religious radio station. They’ve been masterful — Charles Fuller with the old-fashioned revival hour, Billy Graham with his various innovations in communications technology. I think the Internet has been picking up for evangelicals; almost every congregation you can imagine has its own Web site, and they’re jumping on the newest technology as well.

Evangelicals understand that the message is what is important. The vehicle for communicating that message is quite pragmatic, and they’re willing to try a lot of things. One of the reasons for the success of evangelicalism, if you compare it, say, for example, with mainline Protestantism, is that evangelicalism is always looking for novelty. It’s looking for innovation, always looking for the latest edge in communicating to the larger public. In more tradition-bound religious movements, whether it’s Presbyterianism or the Episcopal Church or something like that, you have liturgical rubrics, you have centuries or at least decades of tradition, and people are reluctant to countermand that tradition. Evangelicals have no problem with that. They’re always looking for the latest means to communicate with the public, whether it’s praise music, whether it’s Internet, whether it’s mass communications of one sort or another, and they’ve been very successful.

Most of the reservations about translating the gospel into popular forms come from the academy, the intellectual class within evangelicalism. They worry about that sort of thing, and I think they’re right to worry, because very often the gospel can get translated a little bit too much into the idiom of the culture. In the 1980s you had a really good example of that, with the popularity of the so-called prosperity gospel or prosperity theology. This was the decade of Reaganomics, with the Reagan administration and its economic policies that really were quite unabashed about self-aggrandizement and every boat is going to rise with the tide and that sort of rhetoric. Evangelicalism latched onto that, and that’s one of the reasons why it was so popular in the 1980s.

The day for the popularity of hellfire and brimstone preaching probably is past. It was popular in the 19th century and the earlier part of the 20th century when people really did have an innate sense that the world was a dangerous place, that there was eternal punishment. These days I don’t think Americans feel that so acutely, so it’s a message that doesn’t resonate quite so clearly. But even as far back as the 18th century, Jonathan Edwards is often cited for this famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which is really a hellfire and brimstone sermon. But it was very atypical of his preaching, and throughout American history, evangelicals have quite rightly emphasized the grace of God rather than the anger and judgment of God, and I think that’s what the gospel is all about.

To some degree there has been a lessening of urgency about the spiritual, eternal fate of individuals. A lot fewer Americans generally, and certainly a lot fewer evangelicals as well, believe in eternal damnation and eternal hell and perdition, separation from God. They are much more willing to emphasize the paradise, the rewards of the faith. I think that fits in with the therapeutic culture that is all around us. We don’t talk much about sin any longer in the culture, and you don’t hear it much from evangelical pulpits. When I was growing up as an evangelical 30, 40, almost 50 years ago, I heard a lot of hellfire and damnation sermons, and I don’t hear it that much anymore.

One of the most striking things about the RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY survey is the high number, 84 percent I believe, of evangelicals who believe that being born again or having a personal relationship with Jesus is the ticket to heaven. But if you turn that question around or ask it in a slightly different way and say, “Do you have to have that experience or that credential for entering the Kingdom of Heaven?” far lower numbers were willing to say that. I think that’s probably a function of theology informing their theological responses to that particular question, but if they are forced to turn that around and apply that principle to their neighbors, to their friends and people they know from school or work, whatever it might be, I think they’re much less willing to say those folks also are condemned to damnation. It’s a natural response in some ways; you have these beliefs in the abstract, but if you really are forced to apply them to individuals, it’s a lot less comfortable for them.

Pluralism is a huge challenge for evangelicals. It comes at a time in the late decades of the 20th century when evangelicals really had become fairly complacent about their faith. One of the characteristics of American society is that the First Amendment set up a free market for religion, and you had all these religious groups competing with one another for popular followings. Evangelicals had to compete in that marketplace as well throughout the 19th and into the 20th century; even though they had a hegemonic hold over the religious landscape, they still had to compete somewhat. By the middle of the 20th century they had become fairly complacent about their role in society. Changes to the immigration laws, beginning in 1965, suddenly did change the complexion, quite literally, of religion in America. Evangelicals were unprepared to compete in that marketplace in the way they had in the past. The response generated by that was, politically, the rise of the religious right, which effectively tried to turn back the clock, tried to reintroduce evangelical Christianity as a kind of hegemonic expression of faith for the entire culture rather than compete in that marketplace. I think that’s a mistake. I think evangelicals need to understand how to compete within a religiously pluralistic environment rather than impose their principles on all of society.

Any person has a right to tell someone else that, “My religion, my faith, is better than other faiths.” But in a pluralistic culture, where we value discourse, we value freedom of expression, I think the other person ha[s] the right to disagree, and very often those sorts of discussions do take place. The real danger for evangelicalism is in trying to impose its religious values on the larger society, whether it’s posting the Ten Commandments in the Alabama judicial building or trying to prescribe some form of prayer in public schools. I think that is a mistake, because religion has flourished in this country precisely because the government has, for the most part at least, stayed out of the religion business. Once you begin to specify or to codify religious beliefs or behavior, I think you kill it.

We’re living in a moment where everyone is trying to understand the ground rules, and the ground rules have changed because we are in a pluralistic environment, arguably for the first time in American history, with the possible exception of the 17th and 18th centuries, long before the American Revolution. We’re living in a multicultural, religiously pluralistic context. We all have to figure out how to operate within that context. What is the appropriate form of discourse with someone else? How can I disagree with someone without being disagreeable myself? We’re all trying to find this language, and I think as a culture we’re looking for a common moral vocabulary which right now is eluding us. We haven’t come there yet. We’re looking for a way to talk about values and ethics without drawing on the language of one tradition in particular to the exclusion of all other traditions. And that’s a very difficult conversation to have. How do we talk about morality, how do we talk about ethics in a multicultural context in a way that does no violence to any one group within that multicultural environment? It’s very difficult. That’s the challenge facing us in the 21st century.

There’s no question that there’s been an overreaction on the part of some groups, liberals or secularists or humanists, whatever language you want to use, that have tried to be defensive and even to quash evangelical or more explicitly religious rhetoric in the larger meeting place of cultural discourse. But that’s an overreaction, and we are as a culture still groping toward common ground for discourse in this multicultural context.

Lifestyle evangelism has been effective on the part of evangelicals, and I don’t think it’s necessarily a cop-out. I don’t think it’s disingenuous. If you go back to the New Testament, that’s the kind of evangelism that Jesus himself did. Jesus was incarnational in his approach to the gospel. As an evangelical myself, I would feel much more comfortable with that sort of approach to spreading the faith, rather than preaching it over the airwaves. I’m not criticizing those who do, but it seems to me that incarnational approach to the faith and toward spreading the faith is much more consistent with the style that Jesus had in the New Testament.

Evangelicals are always struggling with exactly what’s appropriate: Should I be explicit about my faith? Should I simply live out my faith? At what point do I move from one stage to the next stage? That’s always going to be a struggle. But living one’s faith is essential to what it means to be a person of faith in a multicultural context. The New Testament calls on us to preach the gospel. If you believe that preaching the gospel means, “I live in a certain way, I hold myself to certain standards of propriety, I live my life with a great deal of integrity; that’s how I’m going to live my faith in this alien world,” then that has a certain legitimacy to it, that has a certain integrity that I honor.

Evangelicals would be hard pressed to draw a distinction between the two. Certainly, an evangelical would feel bound to communicate the faith in whatever way, in an incarnational way or through proclaiming the gospel in one way or another. The general understanding would be that having communicated the faith, it would have a generally ameliorative effect on the broader society and the people with whom you come in contact.

The biggest challenge facing evangelicals is how to communicate their faith. What are the ground rules in a multicultural context? What is appropriate for me as an evangelical making faith claims for myself or for my tradition, listening to others, trying to find a balance in that dialogue that would do no violence to the other and allow the other to be heard, but at the same time representing the faith, my faith, with integrity as Jesus would? We’re still struggling with that. It’s a big challenge in the 21st century in this bewildering multicultural environment.