BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, the moral issue facing and dividing many families: what to do when someone you love is in what doctors call a persistent vegetative state. Do you withdraw the feeding tube, as Michael Schiavo, in Florida, wanted to do in the case of his wife, Terri, over the objections of her parents, the state legislature, and the governor? Or do you keep alive indefinitely someone doctors say will never recover?

Our correspondent, Judy Valente, has the story of another family -- all devout Catholics -- torn apart by their feeding tube decision.

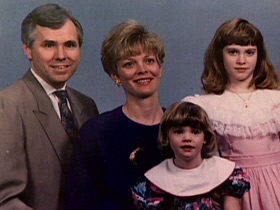

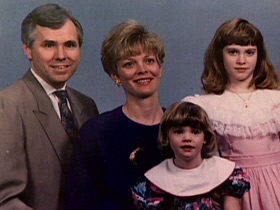

JUDY VALENTE: Hugh Finn was a popular television anchorman in Louisville, Kentucky, and to his wife and family, much more.

MICHELLE FINN (Hugh Finn's Widow): He was a very vibrant person. He was involved with so many things in the community.

ED FINN (Hugh Finn's Brother): My brother was the nicest guy in the world.

Ms. FINN: He above and out was a fabulous family man and husband.

VALENTE: That life, devoted to family and community, took a tragic turn on this rural road one icy morning in March 1995.

Ms. FINN: He had sustained a traumatic brain injury at the scene of the accident. And when I got to the hospital I was informed that he had a tear in the aorta of his heart. I knew that he had gone to the operation room to get the tear replaced. I knew that he had lost a significant amount of blood -- that 11 units of blood that he had lost had deprived his brain of oxygen.

VALENTE: His condition was consistent with what doctors call a wakeful coma. He appeared to be awake but had lost the ability to walk, talk, or control his body. A feeding tube was inserted in his stomach to keep him alive in hopes of recovery.

Ms. FINN: I remember going to the chapel and praying for Hugh. And I -- at that time, I wasn't praying for "Oh please Lord, let him get better." I was just praying for whatever is the right course. You know, "I'm leaving it in your hands."

VALENTE: Michelle was determined to find the best care for Hugh. She brought him to two prominent centers for long-term rehabilitation. Each time, doctors told Michelle they could do no more for Hugh.

Ms. FINN: I was told I really needed to find a nursing home for Hugh, and I was not, at that point, I was not ready to give up.

VALENTE: There were still some signs of hope.

JOHN FINN: He could move his arms, he could move, he would roll around in that bed.

VALENTE: Nearly two years after the accident, Michelle brought Hugh to this nursing home in Manassas, Virginia. There, he could be closer to his parents and some of his seven brothers and sisters. Michelle Finn still hoped her husband would improve. He did not.

Ms. FINN: He was essentially lying in a sick bed existing. We had concerns over bedsores. We had concerns over him getting pneumonia. We had some instances where he was vomiting his own feces. That was actually a complication from the feeding tube.

VALENTE: It was there doctors told Finn her husband was in a persistent vegetative state and that he likely would never recover.

Ms. FINN: I reacted like, well, now I can finally do what I know that Hugh would want me to do.

VALENTE: Michelle believed her husband would want to die. She had talked with her husband philosophically about death just before he turned 40, a few months before his accident.

Ms. FINN: I asked him if he was afraid to die. And he said, "No, I'm not afraid to die." He strongly believed that, as well, he was going to a better place. And that gave me great comfort.

VALENTE: In June 1998, more than three years after the accident, Michelle asked doctors to remove Hugh's feeding tube. She believed her husband's physical ordeal would soon be ending.

But another was just beginning for the entire Finn family. Hugh had not left written directives of what his wishes would be in the event of a catastrophic illness.

It fell to Michelle, as his wife and sole legal guardian, to make the decision. But Hugh's parents and siblings sued to keep him alive. And then Virginia public officials intervened.

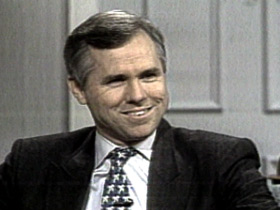

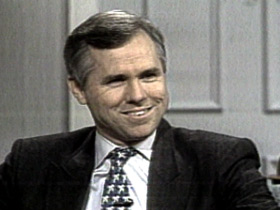

Delegate BOB MARSHALL (Commonwealth of Virginia): We have no reverence for life anymore.

VALENTE: Bob Marshall is a Republican delegate in the Virginia legislature and a devout Catholic. He organized public demonstrations to protest Michelle's decision to let Hugh die and convinced Virginia's governor to file an emergency motion to prevent doctors from removing Hugh's feeding tube.

Del. MARSHALL: Government is supposed to protect your rights. And if it doesn't protect your rights, it ceases to perform its function. The goal of medicine is, or should be, the preservation of life and restoration of health. And when it ceases to do that, it ought not to take up the job of assassins.

JOHN FINN: It wasn't so anybody knew what persistent vegetative state was. It has so many different definitions. My father had seen my brother react and try to communicate with him. Hugh's sister-in-law had seen it. My own sister had seen it.

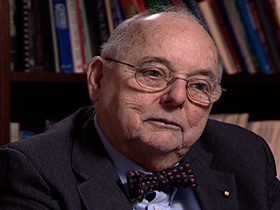

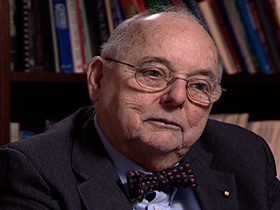

VALENTE: Dr. John Collins Harvey is chairman of the bioethics committee at Georgetown Medical Center. He counsels families who have to face the same kinds of decisions as the Finns did.

Dr. JOHN COLLINS HARVEY (Bioethicist, Georgetown University): Individuals in the persistent vegetative state have reflex actions, including reflexes that will end up in groans and noises that are meaningless, but are there.

VALENTE: Dr. Harvey argues that when there is no hope of recovery, the benefits of keeping someone alive indefinitely on a feeding tube must be balanced between the physical burden to patient, the emotional burden to family, and the cost -- an estimated $60-80,000 a year.

Dr. HARVEY: Moral theologians of the 16th, 17th century on down to the present time have all pointed out that when there is a fatal pathology, we are not obligated to maintain simply biological life. If we maintain biological life that can never recover, we are prolonging the ability of that individual to reach his or her final end, which is life in heaven in glory with God.

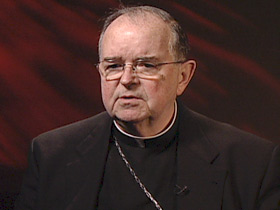

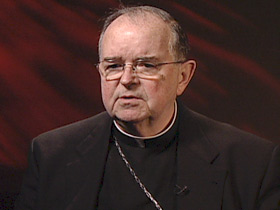

VALENTE: Michelle Finn went to this man -- Archbishop Thomas Kelly of Louisville -- for advice. The archbishop told her that the Church's bias is always toward preserving life. However ...

Archbishop THOMAS KELLY (Archdiocese of Louisville): She was getting all kinds of arguments from certain members of the Church who said that she was basically committing murder. It was suggested that I write to her, and I did. My intent was to say to her, "Michelle, the course of action you're proposing -- that is within the course of acceptable theological opinion in the Catholic Church."

VALENTE: But Church teaching has been far from clear-cut. Many bishops take a stricter view than Archbishop Kelly, arguing it is wrong to remove a person's feeding tube unless death is imminent from other causes. Archbishop Kelly himself stressed that the decision would ultimately be up to Michelle.

Archbishop KELLY: I didn't mean to say it was my opinion or the Church's opinion she should do this. It was her choice. That's very important to remember. She's the responsible one for her husband, and she knew what he would have wished done.

VALENTE: The Finn family, also devoutly Catholic, had a different view.

ED FINN: He was alive. He was a person. And he still had his personality. He wasn't talking or anything, but he was there. He had his emotions. And, well, we have a pretty strong Christian upbringing where what you do to the least of my brothers you do to me.

VALENTE: Finally, Hugh's father told Hugh that Michelle planned to let him die.

JOHN FINN: And he went in and he told my brother Hugh, "That was your wife and she intends to pull your feeding tube and let you die." His reaction was his face soured up, and he gritted his teeth.

VALENTE: Eventually, after a four-month bitter legal battle, a Virginia court agreed that without written directives from Hugh to the contrary, Michelle Finn had the right to end his medical treatment. Eight days after his nutrition and fluids were withdrawn, Hugh died.

He was 44.

Michelle and Hugh's pastor urged the family to reconcile.

Father J. RONALD KNOTT (Pastor, Cathedral of the Assumption, Louisville): If there is anything yet unresolved, now is the time to forgive yourselves and each other. If for no other reason, do it for the sake of Hugh's two children.

VALENTE: The Finn family has never made peace over Hugh's death.

ED FINN: After he was declared dead and he turned, like, a yellowish green from jaundice, from dying of thirst, the hatred and the bitterness -- all that set in.

JOHN FINN: There are too many reports of too many other people who are in this so-called persistent vegetative state that their brain reconnected.

ED FINN: The people who want that person to live, who were already doing the work and putting in, you know, the tender mercy at home, let us do what we want to do. What is so hard about that? What is so inconsistent?

VALENTE: In recent weeks, Pope John Paul II likened the removal of feeding tubes from people who are awake but not necessarily aware to "euthanasia by omission."

Del. MARSHALL: Food and water, that is the line that we should not cross -- we should never have crossed, but we have crossed.

VALENTE: Delegate Marshall has proposed making it illegal in Virginia for a family member to remove a feeding tube without a written directive from the patient.

(To Archbishop Kelly): Archbishop, what would you recommend for people facing a similar situation as Michelle Finn?

Archbishop KELLY: The first thing I would say to everybody is get your wishes in writing. Get your wishes in writing. Put them down.

VALENTE: Michelle Finn now works as an advocate for better government services for people with brain injuries. She has not remarried. She calls her decision a final act of love for her husband.

JOHN FINN: If you really do love that person, do what's best for them and let them come to a natural closure.

VALENTE: Families, meanwhile, continue to struggle over their decision.

Ms. FINN: I loved Hugh's family. They're all wonderful people. Not only, you know, upon Hugh's death did I suffer the grief of his death, although I was somewhat accepting that he was no longer here. I suffered the grief of losing his family.

VALENTE: For now, whether to prolong or end life through a feeding tube remains a largely personal decision -- one that rests on the shoulders of those who must live on with the outcome, whatever it is.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Judy Valente reporting.

ABERNETHY: The dilemma that faced the Finn family also faces many others, among them those whose loved ones are in the last stages of Alzheimer's disease.