BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, a special report. In India, in the foothills of the Himalayas, in the city of Kalimpong, the poorest children have no place to go to school -- except the Gandhi Ashram, where a Canadian Jesuit priest seeks them out, feeds them, teaches them, and gives them confidence -- and violins. Fred de Sam Lazaro tells the story.

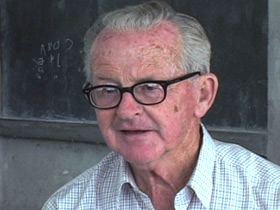

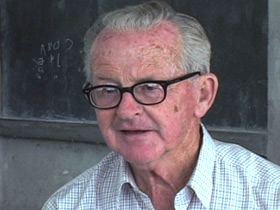

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: At Gandhi Ashram, it is the first day of a new school year. Father Thomas McGuire, a Jesuit, is choosing his newest kindergarten. Gathered around him are children who could never get into another school, whose parents never went to school. He's looking in particular for people called "Biswakarma," that is, those on the lowest rungs of India's rigid caste system.

Father THOMAS E. MCGUIRE, S.J.: We're trying to pick the poorest we can find. If someone comes and tells me, "My name is something Biswakarma," then they've met 80 percent of our entrance tests that we have here.

DE SAM LAZARO: Admission is, most immediately, a meal ticket. It means breakfast, lunch, and afternoon snacks.

Fr. MCGUIRE: Between the Nutella and the vegetables they get in the curry here, it's a rather well-balanced meal -- plain but very nutritious. You'll see after they've finished the meal around here how they'll start running around and sort of giving other witness to the presence of a nutritious meal under their belt.

DE SAM LAZARO: There's not much equipment or playground to run around on. But instead of cricket bats, every child here -- almost from day one -- is provided a violin. Most have never heard the instrument, certainly not playing western music. But listen to the next class. They are three to five years along -- and light years ahead.

(To Father McGuire): What made you think up this whole idea of teaching these kids violin and western music?

Fr. MCGUIRE: Well, I suppose, first of all, because I like it myself very much. I don't play.

DE SAM LAZARO: Father McGuire came here 50 years ago from Canada to teach in the prestigious Jesuit schools. But McGuire also worked the streets, trying to bring into schools the children of people he calls coolies or laborers. Because these children were more likely to be academically behind, McGuire began looking for activities at which they could excel. One day he asked a visiting violinist from the Calcutta symphony to play for the street kids.

Fr. MCGUIRE: I told him they might giggle or laugh or that sort of thing, and he said, "Fine, I'll be ready for that." He played for well over an hour, and it was just rapt attention. So then I thought maybe they might take an interest in this kind of music.

DE SAM LAZARO: In fact, they excelled at it. Ten years ago, when he started his own school, McGuire hired some of the coolie children he'd adopted years before to be teachers, including music director Rudramani Biswakarma.

Fr. MCGUIRE: Rudramani was a boy who had, as we proved later, extraordinary ability in music, native ability. Now, I first met Rudramani in the streets of Darjeeling when he was seven or eight years old, and he was just a coolie. He was earning his own livelihood.

DE SAM LAZARO: Under McGuire's tutelage, he went on to get a college degree and, remarkably, just in the past two years, hearing aids to correct a severe impairment he'd endured since childhood. Rudramani says few words. His passion and eloquence are more evident in music. He plays, teaches, and arranges everything from Mozart to movie scores to Nepali folk songs.

Fr. MCGUIRE: You can see that they're interested in music, that they picked it up quite quickly, and they picked it up from one of their own. I would bet you that 95 percent of the children I have here have never owned a toy. All these children can do is sit around and play Mozart. Lucky kids. They can't go and listen to "boom, boom, boom" or "rrrr rrrr" on TV.

DE SAM LAZARO: This is Kushmita Biswakarma. Her parents labor on farmland in exchange for food and space for their tin-roofed home.

MOTHER OF KUSHMITA: We are happy, very happy.

FATHER OF KUSHMITA: We're happy to see them go to study because we, of course, did not have a chance to study. Now they are able to get an education; they can have a better life than we did.

DE SAM LAZARO: For Kushmita and about 30 other older students, like Milind Lepcha, McGuire has gotten scholarships to attend the so-called mainstream schools.

Fr. MCGUIRE: It's a big break, but it's also a social challenge to fit in. That's where their violins fit in -- providing a boost in self-confidence.

DE SAM LAZARO: Were you able to make friends?

KUSHMITA: Yeah. I was able to make friends because I was good ... in school, like, in the program, I used to play violin. I used to play solo songs, like Hindi, Nepali songs, you know. They all used to love me playing violin. I had many friends, many friends I had in the convent.

DE SAM LAZARO: Because you were able to play violin?

KUSHMITA: And I was good also.

DE SAM LAZARO: You were good?

KUSHMITA: Yes.

DE SAM LAZARO: So good, she was pulled out of school to be tutored by a visiting music teacher from Germany, in hopes of attending one of Germany's prestigious music conservatories.

KUSHMITA: Before, I did not know the rules and the way ... how we should play violin. Afterwards, when Margaret came she taught me how I should hold my bows and how I should cast the violin. I want to come back to Kalimpong because my parents are here; I was born here. I studied at school in Kalimpong.

DE SAM LAZARO: Would you like to be a teacher in Kalimpong someday? Teach music at Gandhi Ashram?

KUSHMITA: Yes.

DE SAM LAZARO (To Father McGuire): You belong to the Society of Jesus. In this Hindu majority school, where does Jesus Christ figure?

Fr. MCGUIRE: Well, my Christianity, as lived here, is trying to get breakfast for those kids in the morning, eh? Go out and develop your talent, eh? God created you for a purpose. God has a purpose in mind for you in this world today. What is it? You find out!

DE SAM LAZARO: He says few of these kids would likely want to make a career as musicians. But music has been their ticket to an education and a ticket out of generational poverty. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred De Sam Lazaro in Kalimpong, India.

KIM LAWTON, guest anchor (August 5, 2005): A footnote to that story: Kushmita Biswakarma has been admitted to the Konservatorium Richard Strauss in Munich, Germany, where she is pursuing her musical education.