BOB ABERNETHY: Now, a special report. Twenty-five years ago this past week, in Greensboro, North Carolina, there was a shooting that left five people dead and the city polarized. But recently, a group of volunteers formed what they call a Truth and Community Reconciliation Project. The idea is to try to find out what happened that day and, the organizers hope, to create some forgiveness and healing. Lucky Severson has the story -- which includes dramatic film footage of the shootings.

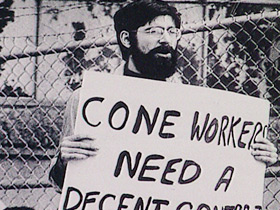

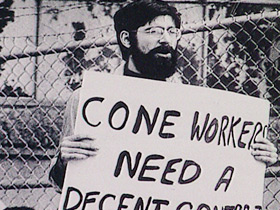

LUCKY SEVERSON: The Reverend Nelson Johnson, reliving the violence in Greensboro of 25 years ago that he can't seem to get out of his system:

Reverend NELSON JOHNSON (Pastor, Faith Community Church): It was right in this area that Cesar was shot and Jim was shot. People were within 15 yards of each other.

SEVERSON: Where were you?

Rev. JOHNSON: Actually, I was on this side of the street when I was stabbed, when the shooting started.

SEVERSON: It was November 3, 1979. Johnson was at an anti-Klan rally and parade sponsored by the Communist Workers Union Party. Several cars carrying Klansmen and Nazis showed up uninvited. Shots were fired. Minutes later, five demonstrators were dead. Ten others, including Nelson Johnson, were wounded.

On this Sunday at his Faith Community Church in Greensboro, Reverend Johnson is still trying to reconcile himself to what happened.

Rev. JOHNSON (Speaking to Congregation): Isn't truth a good thing? Isn't reconciling people a good thing? Isn't restorative justice a good thing?

SEVERSON: Reverend Johnson was a driving force behind the recent creation of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission, fashioned after those in South Africa, Rwanda, and other countries that have attempted to come to terms with their past. It's the first of its kind in this country.

The seven-member commission, which is privately funded, has been given 18 months to complete its mission, which includes reviewing evidence and interviewing witnesses. But unlike some commissions, this one has no legal standing to compel testimony -- or even to indict.

Rev. JOHNSON: We have no interest of placing anyone in jail. Most of the people who were trigger pullers and police officers are up in years. It would really defeat our purpose to do that.

SEVERSON: Still, there have been other commissions with no subpoena powers that have been quite successful. According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, which has worked with several commissions, including the one in Greensboro, countries like Peru, El Salvador, and Guatamala have apparently all benefited from the truth-seeking process.

Observers say even when perpetrators haven't come forward, the testimony of the victims, although painful, often proves to be cathartic. The goal of all these commissions is to prevent what happened from happening again.

But Greensboro Mayor Keith Holliday says what worked elsewhere won't necessarily work here.

KEITH HOLLIDAY (Mayor, Greensboro, NC): I don't think they are going to get more to the truth than what we already know what the truth is.

SEVERSON: Despite the mayor's skepticism, the commission appears to have fairly broad-based support from throughout the community. Still, the mayor thinks the commission will do more harm than good.

Mayor HOLLIDAY: A lot of eyes from across the nation are going to look at Greensboro and re-conjure up the image that Greensboro's a battleground. And this wrong perception of Greensboro is going to be portrayed across the country at a time when that is the last thing that we want.

SEVERSON: There was a time when Greensboro was a battleground. The sit-in at the Woolworth's soda fountain in 1960 put Greensboro on the civil rights map.

Mayor HOLLIDAY: It really sparked the revolution around the country for sit-ins. And of course, we are very proud of that.

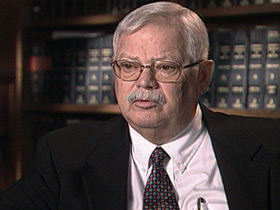

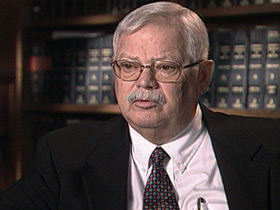

SEVERSON: It wasn't that Greensboro had more racial problems than any other Southern city, although it had its share. But after the famous sit-in, Greensboro became a symbol of the struggle for equality. Some say the deadly rally in 1979 was mostly about race. On the other hand, Harold Greeson, an attorney for one of the Klan defendants, says the rally was nothing more than an attempt to organize workers in Greensboro's textile plants.

HAROLD GREESON (Attorney): I suppose since the incident took place in a black neighborhood in Greensboro, some would think it was race, but it was a bunch of communists who staged the rally hoping to gain some recruits for membership in unions -- taking over the country by taking over labor unions.

SEVERSON: Signe Waller was one of the rally organizers that day, a member of the Communist Workers Party. She says it is impossible to separate race from workplace equality.

SIGNE WALLER: Racism is interwoven in the whole fabric of the social system. You can't really separate it. We were organizing workers across racial lines. That was very threatening to some people, the Klan.

SEVERSON: Signe's husband, Dr. Jim Waller, a pediatrician, was one of two doctors gunned down that day.

Ms. WALLER: He really cared about people: very humble; perfectionist; thought about other people. He was thinking that he had to help people, that he had to save lives.

SEVERSON: The only woman and the only African American killed was Sandi Smith.

Rev. JOHNSON: Sandi Smith was like a young sister to me. It was a heartbreaker to have to call Sandi's mother -- to tell her that her beautiful, young daughter, an excellent student, was shot in between her eyes trying to help children get out of the way, out of a barrage of bullets.

SEVERSON: But attorneys for the Klan and Nazis said their clients were shooting in self-defense, that the demonstrators started firing first.

(To Rev. Johnson): Did people with you fire at the Klansmen, shoot their guns?

Rev. JOHNSON: Only after they were fired upon.

SEVERSON: They did not fire first?

Rev. JOHNSON: Absolutely, and the FBI report will attest to that.

Mr. GREESON: Our guys came here, the testimony showed, with eggs that they had purchased along the way.

SEVERSON: And guns?

Mr. GREESON: Pardon me?

SEVERSON: And guns?

Mr. GREESON: They had guns in their trunks. Klansmen always have guns in their trunks. That's what they do at Klan rallies; they trade guns.

SEVERSON: It's true that the demonstrators did have some guns, and fired them.

Rev. JOHNSON: Imagine what would have happened if there had been 15 or 20 in our group who had rifles or shotguns and were fired upon. Then you would have had casualties on both sides. You would have had massive casualties on both sides. Except no one was killed on one side, no one was injured on one side.

SEVERSON: There's no doubt that when the Klan showed up, they would not have been happy with the chants and placards that said, "Death to the Klan."

Ms. WALLER: Because we said it that way, it was used to show the antagonism between ourselves and the Klan. It was an unfortunate slogan. We wouldn't do it today if we knew what we knew then.

SEVERSON: What troubles people who were there more than anything was that police didn't show up until after the shooting was over, even though they had promised to protect the marchers. Police said organizers changed the start time. But local television news crews managed to be there. And later in court, it came out that there was a police informant, a former Klan member, who notified the Klan about the march route and time.

Rev. JOHNSON: It essentially was a government-sponsored death squad, when you go through all the trappings and see there would have been no Klan and Nazis here had not a government agent invited them.

Mr. GREESON: I know that this was a simple case of the organizers firing shots and the Klansmen returning shots, and that's the truth.

SEVERSON: There were three trials. The first was in state court, the second in federal court, where all-white juries found the defendants not guilty. The third civil trial found two police officers, one police informant, and several calling themselves Klansmen and Nazis liable for the wrongful death of one protestor. The city settled out of court.

The lingering suspicion here is that someone literally got away with murder. And it troubles Reverend Johnson that this effort to clear the air isn't getting more support from local churches.

Rev. JOHNSON: And yet this great experiment in truth seeking and grassroots democracy and restorative justice and reconciliation, some churches have urged their members not to become involved. Can you understand that?

SEVERSON: Even the mayor, who opposes the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, says he thought there should have been a different outcome.

Mayor HOLLIDAY: I would be real honest to tell you that I did sit in and heard a lot of the trial. There is zero doubt in my mind I would have found someone guilty. Probably more than one. I was very surprised that they were acquitted.

SEVERSON: Councilwoman Yvonne Johnson says the lack of trust is why the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is necessary.

YVONNE JOHNSON (Councilwoman, Greensboro, NC): I think what is more damning is not to try to heal it, to not just call it what it was, and to do some forgiving of whoever needs to be forgiven.

Mr. GREESON: I don't believe anybody is really interested in the truth. I think it's an attempt to keep the matter alive by a handful of people who find it in their best interest to do so.

Ms. WALLER: I'm prepared to forgive the people responsible for these deaths, including my husband's. It's something I need to do. But I think the whole community -- there are many people and institutions that need to be accountable and perhaps forgiven here.

Rev. JOHNSON: I have great faith in the power of truth, even though it comes slowly and at some expense. It is a powerful thing when done in the right spirit.

SEVERSON: For the survivors of that day, like Nelson Johnson and Signe Waller, and for many in Greensboro, the commission is a way of getting to the truth, then hopefully finding forgiveness. The commission's challenge, and it won't be easy, is to heal the old wounds without opening new ones. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Lucky Severson in Greensboro.

ABERNETHY: At the trials after the shooting, none of the surviving demonstrators or relatives of victims testified. The leaders of the Greensboro project hope people can now tell their stories, and that that process alone will be helpful. Testimony is expected to begin at public hearings early next year.