In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

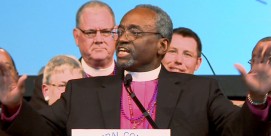

Bishop Frank Griswold Extended Interview

Read more of Kim Lawton’s interview with Episcopal Bishop Presiding Frank Griswold in New York City on October 6, 2004:

Q: Let’s start by talking about the new Lambeth Commission Report. What did you say in the House of Bishops meeting about how the U.S. church will be receiving this report?

A: It’s very important for us in the United States to receive the Lambeth Commission Report on communion in a generous spirit and in a humble spirit. One of the realities is the Episcopal Church, by association with United States policies – which are perceived in other parts of the world as very self-serving if not unhelpful to other societies – I think often the Episcopal Church is so associated with American policy abroad that we are thought of as arrogant and insensitive to other cultural realities and other concerns, and therefore it’s very important that we receive this report seriously, with openness of mind and a genuine desire to find ways in which we can be better partners with other parts of the Anglican world.

Q: In the years since the General Convention, how much hurt, how much anger, how much confusion have you heard about from some of these partners?

Q: In the years since the General Convention, how much hurt, how much anger, how much confusion have you heard about from some of these partners?

A: I’ve had the advantage of being able to travel to other parts of the world. I’ve been to Nigeria, where I gave a retreat to the bishops of Nigeria and visited a number of dioceses and saw the work and understood some of the complexities of life there. And the same is true also in Uganda. And therefore, I’m very aware of how different the contexts are in which, let’s say, the Anglican Church in Nigeria or Uganda is seeking to interpret and live the Gospel. And then in contrast, I’m very aware of different realities that are present here in the United States. And in fact, one of the primates, not from a Western country, said to me, “I think the Holy Spirit can do different things in different places.”

One thing about Anglicanism – and this is in some of the documents that have been generated by such things as the Lambeth Conference – the Anglican tradition realizes that the Gospel is locally embodied, and therefore it’s going to be affected by cultural and political realities in different parts of the world, and therefore what may seem to many people in the United States as a genuine unfolding of a Gospel direction may in another part of the world be seen as extremely unsettling and threatening.

So, I have a very deep sense of the complexity of all this, and it’s further complicated by the immediacy of communication. I mean, years ago, no one would have known about the ordination of the bishop of New Hampshire until letters had arrived some months later. But now, television, for example, beamed the ordination service around the world, so suddenly it was as if it were happening in Nigeria and other places. And so, naturally, the reaction was more intense because here it was, right in my own living room.

Q: When you as a church are making those determinations of how the Gospel is embodied in a particular context, where is the line at which point it’s not the same church, or the beliefs are so different that it no longer is still the same body?

A: I think what is very disturbing to me at the present moment is that sexuality seems to have trumped the creeds in determining fundamentals of the Christian faith. And the truth is that a great deal more unites us than divides us. There’s a common appreciation of the creeds as the ground of our articulated faith, and we all believe that the Old and New Testaments contain everything necessary to salvation. And then the interpretation of Scripture becomes something that varies. Even the primates themselves, when they met last October, in their official communications said there are differences in how we interpret Scripture, and we need to acknowledge those things.

Q: I want to ask you to simply explain this notion of a communion. I think it’s difficult for people outside the Episcopal context to understand what that means – how the U.S. church is autonomous, but yet in relationship with all of these other churches. How does that work?

A: There are two important things about communion. First of all, communion is a gift from God and not something we simply create. Communion is the intimate life of a relationship that exists between the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit that is then expanded to human beings through baptism, and we are all then connected in what Paul calls “the body of Christ.” He says we’re all limbs, members of this body – arms and legs and constituent elements of a body. So, communion is about deep relationship created by God.

Now, the Anglican Communion exists not juridicaly – I mean – there is not a pope. The Archbishop of Canterbury does not occupy that kind of position. But communion is a matter of relationship on many levels. And so, though there may be strains formally between the heads of the various churches of the Anglican Communion, relationships also continue on the ground, and they are much more intimate. They are sometimes bishop to bishop, or a group of women from one part of the Anglican Communion, for instance, came here to New York to be part of a U.N. conference, as Anglican women, about women in the world. Well, this is a manifestation of communion.

So, it’s not a formal relationship so much as it is a kind of lived pattern of many relationships. And I think, too, it’s important to point out that the Episcopal Church, which was the first, as it were, breakaway from the mother church in England, saw itself as quite independent, and the notion of Anglican communion really is a more recent development, as largely British missionaries went to various parts of the world and established churches in what were British colonies. So the notion of communion has evolved, and it is still evolving. And I think part of the present strain is, what is the proper relationship between the local reality and an international body of churches in fellowship with one another, and where does the action of one church drastically affect the life of the other churches?

So, this is part of what we’re struggling with. And I think the Lambeth Commission report will help us in that struggle.

Q: To what extent do you think that you are in some ways redefining or evolving the notion of how all of these Anglican bodies relate to one another and live together or don’t?

A: Well, my hope and my prayer is that we will find a way to continue to be partners. For instance, there is such poverty and disease and internal turmoil in various parts of the world where we have resources that can be helpful and useful, and we want to be in a living relationship with brother and sister Anglicans who are dealing with HIV/AIDS, for example.

So, my hope and prayer is that the Lambeth Commission report, which really, as its title suggests, is about communion, will really be an invitation to live what I will call a more sacrificial life, not just on our part but on the part of everyone, to make a little more space for one another, because in this shattered and broken world where division is the order of the day, I think it’s so important that the church manifest a capacity to contain difference with grace and focus its attention on human need. After all, the church doesn’t exist for itself, it exists for the sake of the world and the world’s well-being.

Q: What is the U.S. church’s responsibility as a church here to deal with the people here, and then to what extent should outside voices have an impact here, as the church here deals with the people here?

A: I think when you look at the Episcopal Church you have to ask the question, “What kind of church has it been historically?” And you have to go back to the 16th century, when the Church of England, our parent, came into being, and at that time you had on the one hand reforming zeal, and on the other hand you had a sense of Catholic continuity. And these two really were at loggerheads with one another. But the Anglican solution, Anglican comprehensiveness as it’s sometimes called, saw containing those two realities within one reality, namely the Church of England, rooted and grounded not in perfect agreement, but rooted and grounded in a capacity to pray together. And so in the Anglican tradition, the liturgy has always been this sort of meeting point for difference, where difference is reconciled, not at the level of the head but at the level of the heart. Historically, we’ve always been a church that can contain and live difference.

So, that brings us now to the present moment and I think the overwhelming reality of the Episcopal Church is what I would call “the diverse center,” people who hold a variety of opinions, not just with respect to something as emotional as homosexuality, but all kinds of other things – war and peace, should we be involved in military operations or not? You have a church that has multiple points of view and by-and-large can live with that multiplicity of points of view because of the sort of common focus beyond ourselves, mediated by the liturgy, namely the person of Christ.

So, we have people on the edges, and people on the edges always are more loudly heard, I think, than the diverse center. And I don’t want to overly complicate the situation by describing something too diverse and strained, but still, I think it’s important to say that even within this diverse center you have people who are deeply pained by actions of the Episcopal Church in recent days, and others who are overjoyed, and yet they’re able to live together. Our recent meeting of bishops is a perfect example of people with diverse opinions being able to come together and say, “All right, for the sake of the world, what should the church be doing?” and sort of looking beyond ourselves.

There is this concern about ministering to all points of view, and certainly as the presiding bishop I see myself as belonging to everyone even though I have my own points of view. I care as much for people who are distressed as people who think the actions are inspired by the spirit.

Now, internationally, I am very aware, as are the bishops – and they said this in their recent letter – we’re very aware of the complications and difficulties the decisions we’ve made have caused in other parts of the world. And this is part of, I would say, the tension between trying to be faithful to what you perceive locally – yes, being sensitive to other parts of the world, but also acknowledging the fact that ultimately you have to live within your own context. And we, as a result of that, are certainly going to seek every way and are seeking every way we can bridge the gap and be authentic partners with other parts of the Communion.

Q: Is this truly a time of crisis? Is that how you look at it?

A: If you look at the Episcopal Church through the eyes of its parishioners, which I think is probably a realistic way to look at the church, see what actually is going on – on the ground, the overwhelming majority of congregations are focused on things like Sunday School, adult education, how can we meet the needs of the community in which we find ourselves, how might we be related to a parish in a diocese in some other part of the world. Things like the Lambeth Commission Report seem awfully remote, and some of the struggle seems awfully remote.

I’m not saying that’s universal. There are congregations that are deeply upset, and some that are deeply divided, but the vast majority are focused on what does it mean to be a Christian community, what does it mean to exist not for ourselves but for the sake of the world? That is the larger reality of the Episcopal Church, and I think probably that’s the larger reality of most of the Anglican Communion, if you look at it on the ground in terms of its congregations.

Q: Is it frustrating to be so focused on this and asked about it all the time as opposed to so many of the other places where the Episcopal Church is involved and issues that the church is wrestling with?

A: I find the endless fixation on sexuality, and more specifically homosexuality, a distraction from other areas that quite frankly are matters of life and death. I remember vividly, when the primates met last autumn in England, at the end of our meeting, which was focused mostly on the blessing of same-sex unions in a diocese in Canada and the actions of the Episcopal Church in confirming the election of the then bishop-elect of New Hampshire, one primate said, “You know, it’s been sex, sex, sex, and I am facing poverty and disease and life and death in my diocese, in my church.” And several of the other primates just sort of sighed. And I apologized. I said, “I am very sorry that this issue has been made center stage in the life of the Anglican Communion,” and I went on to say, “and that has happened in large measure because of people within my own church who are unhappy, who have insisted that this be the issue in the life of the Anglican Communion.” So that does sadden me deeply. And when I retire as presiding bishop, I hope that I’m known for something other than this issue.

Q: Has it been challenging for you spiritually, physically, and emotionally to be presiding at this time?

A: It has not been easy to be the presiding bishop in this season. I must say I am well served by a wonderful spiritual director who once said to me, “What other people say about you is none of your business,” and that was very helpful. I realize that a lot of the anger and upset, and indeed, some of the elation as well that gets focused on me isn’t so much about me as myself as [it is about] me as symbol. I make a distinction, insofar as one can, between myself as myself, and myself as a “role,” and therefore, sort of a focal point for any number of perspectives within the life of the church. I think my role, too, and my basic task is to keep as many people at the table as possible, and to remind everyone that though they have their own particular point of view, there are others who have another point of view, and they are equally members of the church, loved by God, members of Christ’s risen body, and therefore must be taken with full seriousness. And it’s in the tension, often, that the truth, whatever it may be, gets more fully revealed.

Q: How has all of this affected you spiritually?

A: Spiritually, this has all deepened my companionship with Christ. It has also made very real to me the whole notion of sharing Christ’s sufferings in order to share Christ’s resurrection. I mean, dying and rising, which is the basic paradigm of Christian life, seemed in some ways a bit abstract before I became the presiding bishop, and now it seems very, very real indeed. As I read the psalms each day in morning and evening prayer, many of the psalms are about people in a situation of suffering and feeling isolated and alone, and nevertheless, “I know you’re with me, God.” I mean, those psalms take on an immediacy that they didn’t have before.

Basically, I think I’m a happy person – not with my own sort of manic joy but with something the Holy Spirit has sort of worked in me. And I think this is what gives me a sense of graced confidence, you might say, and an ability not to be sort of thrown off course by these curious things that sort of erupt in the life of the church.

Q: What are you hearing from the Anglican churches in Sudan, and what do they want to see the U.S. do – not just the church, but the U.S. government, the U.S. as a nation?

A: The Sudan is very close to our hearts because there is an Episcopal Church of the Sudan, and at our recent meeting of bishops in Spokane, one of our guests was a bishop from the Darfur area. We have been, as a church, very focused on legislation. We’ve brought Sudanese bishops to testify before Congressional committees. Congregations across this country are in solidarity with the church in Sudan. Our Episcopal relief and development organization has received, I think, about $1.5 million for relief in the Darfur area. We’re trying to be partners in terms of political leverage and in terms of direct service, and trying to make the situation, as our brother and sister Anglicans can describe it in vivid detail, that much more real and immediate in the lives of our people, and certainly in the lives of our legislators.

Q: And what do they say that situation is? What are they suffering?

A: You could listen to a bishop tell you about his family being killed in the compound, and just chaos – I mean, a chaos to an extent that you can’t imagine how people can function. What has been so amazing to me is the power of a kind of deep faith, and indeed, a hopefulness in the midst of situations that from our point of view seem absolutely hopeless. Our faith is rendered so shallow, in a way, in comparison to the heroism with which the bishops and clergy and lay people in the Sudan are able to witness to the Gospel under the most appalling circumstances.

Q: You are a good friend with the Episcopal bishop of Louisiana.

A: Bishop Charles Jenkins and I go back to when he was ordained a bishop. In fact, I was scheduled to give a retreat to the clergy of his diocese before he was elected. He attended the retreat and we became, out of that experience of praying together and reflecting on the life of ministry together, very, very close friends. I think the fact that Bishop Jenkins and I have somewhat different views on matters of sexuality, but are absolutely of one mind on everything else, has been a very good example to people on both sides of the question, of people who can care deeply about a mission they share for the sake of the world, and disagree on some things, and yet make common cause in the name of Christ.

Q: Does he challenge you? Does he push you a bit on some of these things?

A: If anything, Bishop Jenkins teases me. He has an outrageous sense of humor. I would say we were both aware of our different perspectives, but we simply accept the fact that there are different realities within one church, and those realities are going to continue, and they need to be respected. And sooner or later the Holy Spirit will figure out how they might be reordered, but for now we live our two integrities together as brothers in Christ.