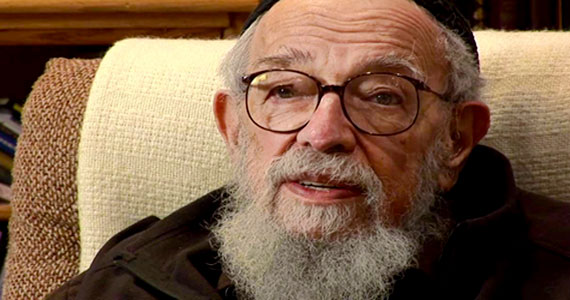

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi Extended Interview

Read more of producer Susan Goldstein’s interview about the Jewish Renewal movement with Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi:

Q: What is Jewish Renewal?

A: Let me begin with the issue of renewal itself. There are some people who after the Holocaust felt that we have to do restoration. We have to get back to where Judaism was before Hitler decimated 6 million. And it was such a deep cut, as it were, of vital power and energy of our people. When the refugees came, they settled in enclave[s] in New York and elsewhere and in Jerusalem, and they wanted to reconstitute what they had before, namely, they were restorationists.

And that’s how I began first, because I read the Dead Sea Scrolls, and I was very much impressed by the original of all monastic stuff in Christianity and even the dervishes in Islam, which was with the Dead Sea community. And the first group that I brought together was called “Be’ Nay Or,” because it was based on the scroll of the children of light against the children of darkness.

However, as time went on, the kind of community that I wanted to create, which was a monastic urban kibbutz — it didn’t come to be. And more and more, I felt that the people here in America needed first of all to lower the threshold and then to find ways where in this setting we could renew those values and those experiences that were there before.

The most important thing was to remove all the debris that was between souls and God. And so, therefore, I took the Hebrew prayer book — and working with it is called “davening,” which I believe comes from the word “davenum,” just as when we say the grace after [a] meal we call it “benching,” from benediction. When people start[ed] to daven, they didn’t know how to do it beyond reciting. So, therefore, I looked into the way in which I had been taught in the mystical tradition in Chabad and Lubavitch, and with this introspection I was able to learn how one moves on the inside, because it doesn’t have external markers.

I created something I called “davenology” in order to help people be able to go into that experience. Having done that, it became also clear that we had to do a theological job, which was that every religion has the magisterium, the teaching part of the religion, and it also has a cosmology, a reality map. And the reality map [for] most of the people trying to do restoration was an old reality map. It didn’t fit anymore. In other words, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Auschwitz, Birkenau, moon walk, fifth-generation computer, the whole story of the universe has changed. We are not talking about fields; we are talking about string theory. We’re talking about a whole other thing in quantum stuff, and that hasn’t yet been incorporated in our theology. A theology that’s out of date cannot get the loyalty of the people in the present.

So that was dealing with the more conceptual stuff. But beyond that, ever since what we call scientism and the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century, what you couldn’t touch and what you couldn’t see, what you couldn’t measure didn’t exist for people. But then out-of-body experiences and all the old stories that people had been telling about spirituality and so on, so forth started to come back into view. And the question was: How do we take the teachings of Jewish mysticism and make them applicable to our day? Jewish Renewal is all that.

Furthermore, there’s an element of medieval awareness that said the body isn’t good, the soul is good. Leave the body behind or suppress the body and opt for the soul. Now that we’re talking holistic stuff, it didn’t make any more sense to do that. Also, Earth is suffering. If we could hear the outcry of Earth, her air, her lungs have emphysema. Her blood circulation, meaning the water table and so on, so forth is poisoned. And she has fever with global warming.

So when you look at all these things, the outcry, then the question comes: What is there in the way in which we deal with our commandments that would help heal the planet? We discovered something else — that much of our understanding of Judaism was very masculine, patriarchal, and was therefore left-brainish, and it didn’t have enough of the [imagining] of the heart and the intuitive. Jewish Renewal brought all these things together.

Q: Why is there a thirst for spirituality? Why do people yearn for the experiential?

A: Let me begin, first of all, with something that happens in all mysticisms. There is a four-level way in which people deal with things. There’s hatha karma yoga, one level. There’s bhakti yoga. There’s gani yoga. And then there’s raja yoga. In our understanding, we speak about the four letters of the divine name and the four worlds. Where does this come from, that all over, wherever you go, you find these four — or five, in Chinese medicines? Jung would talk about the quaternity and so on. [It is] because we’re hard-wired that way. We have the reptilian brain. We have the limbic part of the brain. We have the cortex, and we have a whole bunch of uncharted stuff that deals with intuition. We needed to become aware of that, because if you only live on this level, which is consciousness of the shopping mall mentality, then the needs that we have would all have to be dealt with on this level.

A rabbi friend of mine put it this way: “When I was a baby, when I was hungry, my mother took me to the breast, and it was good. And when I was lonely and I cried, my mother took me to the breast. When I was upset, my mother took me to the breast. And now I’m grown up. When I’m hungry, I go to the fridge. When I’m upset, I go to the fridge. When I’m lonely, I go to the fridge” — which means that we haven’t learned that our needs happen on other levels, and we still are trying to fulfill them on the bottom level, which is precisely what advertisement wants us to do. If I long for a beautiful woman, she’ll sit on the car that I should buy in order to get her. Advertisement is always built on trying to keep us on this lowest possible plane. But the hungers happen to be on other levels. Once you become aware that the bigger hunger is not for more conceptual stuff, it is for more heart, and it is for more of the intuition that allows each person to have the initiative over his own soul life. Whereas in the other situation it was always, “Clergy will tell us how to do it.” It comes from a heteronymous thing rather than autonomy and the soul.

But after this kind of paradigm shift, people want autonomy, and they want to have their self-experience. It began in the ’60s and a re-sensitizing where we are. And then later on, more intuitive stuff, and gestalt and psychology moved from behaviorism to Freud and then to humanistic psychology to transpersonal psychology, all of which is in order to fill that need, that hunger that people have for the intuitive and the emotional.

Q: But is it also a hunger for relationship with God?

A: That’s precisely the point. The definitions we had of God that were the old ones had to be discarded. No person can really have a real relationship with God unless they have been an iconoclast first. Abraham had to smash the idols of his father, and so we have to go through the same thing. We have to smash the idols of our childhood in order to get to a more mature God. But it turns out that philosophers have made God disappear from us by wanting God to be the omni, omni, omni, and that took away the heart connection, which is to say the root metaphor that each person has to have.

William James once asked a deacon in New England, “What do you do when you see yourself in the presence of God?” He said, “I see an oblong blur.” Well, the oblong blur is not what the heart can use. The heart needs to have a relationship word. So we talk about “father.” “Father” after Freud wasn’t so good. “Judge,” “king” — these words don’t work anymore.

So this is why our people have gone to speak of Melech instead of Melech Ha’olam, “king of the universe,” “the spirit of the world.” In other words, the life force in the world. With that we can have a connection, because the life force operates in us.

How do I know there is a God? Listen to the pulse. I don’t beat my pulse myself. The voice of my beloved is in the pulse. Once you begin to speak about the longing that we have and you sing the melodies that bring the longing to the fore, and you express that in prayer, in that longing there is a response that comes from the universe. [It is] the best way in which we can say that this is God. But the word is such a bad word. It’s because it’s become so contaminated by people pushing other people around with that word.

Q: Christians talk about a personal relationship with God, so when you say that it sounds very Christian.

A: This is so funny, because it looks to me the other way. Jesus is so thoroughly Jewish, and he talks about God as Abba: “Our Father who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy name.” The Judaism has been filtered out for Christians, so they don’t know anymore what his origin is. And the worst thing yet is with Islam. They don’t understand what they owe to Judaism when they speak about the relationship to Allah. We need to just make this very clear. When you speak about the Ba’al Shem Tov and Hasidism and so on, it becomes very, very clear that there was a personal relationship. Just four generations ago for many people here, their mothers would put on a kerchief and say the prayer over the candles and then pray for every member of their family at that time and pour out their heart. People came for Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur. Even Rudolph Otto describes “the idea of the holy.” He says he came to a synagogue, and he discovered it when people were praying, because when you say “Baruch atah adonai,” you’re addressing God.

I remember when I was a child, my dad had just finished his prayer, and I peeked underneath his tallit, which he had over his head, and I saw he had been crying. So I said, “Papa” — I was speaking German at that time — “why do you cry?” He said to me, “Because I talked with God.” So I said, “Does it hurt when you talk with God?” And he said, “No, it doesn’t hurt. It’s very good. I only cried because it was so long since I last talked to him.” You get the sense that the personal was very, very real in everything that we did. It was only from the 1920s, I would say, to the late ’60s, ’70s that even in most synagogues God was absent.

Q: There are apparently disaffected Jews who are turned on to Judaism because of the renewal movement. Why was God absent in the synagogues, and how has renewal reenergized synagogue life?

A: I don’t want renewal to be seen as a denomination, but rather as a process, as a moment. Any revitalization, any connection that we have with that which is beyond ourselves and in ourselves at the same time is a revitalization, and it happens to some people in Orthodoxy and some people in Reform, and even it happened to one young woman who was just ordained who was serving a community that was humanistic Judaism. She mentioned God and she was fired.

There was this attitude that people had because very often oppression came connected with God — oppression by clergy, oppression by rabbis, oppression by people who couldn’t understand one generation. There was such a gap between one generation and the other, and they couldn’t bring God across.

Another element: as long as we had three generations in one household, then the grandparents could talk to the grandkids because both of them had an enemy in the middle. But once it happened that we now have these nuclear families and single-parent families, family values have to be rejected by the next generation.

Q: But tell me about synagogue life. You were saying that God was absent from institutional life. Why was that, and how did Jewish Renewal help?

A: First of all, it went back to reform in Germany that wanted to make sure that Judaism was the religion of reason. And reason then took God into “god idea.” “God idea” is just a concept, and the living God is not a concept. After all the “god ideas” had evaporated, the best thing that in many synagogues they could hear is, “We live under the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man,” and it didn’t mean very much, because you didn’t have a personal relationship.

It’s not true that that was absent completely, because there was a Reform prayer book for home use. [It] was pious, if you will, very heartful. But the pulpits were not doing that, and so people didn’t have a connection with that, and they talked a lot about Israel, which you need to talk about, about United Jewish Appeal, about helping to rebuild the infrastructure, bringing refugees from Europe, helping Russian Jewry. A lot of the time these were the topics in synagogues.

Q: You were influenced by other faith traditions. You took a trip to meet with the Dalai Lama, Thomas Merton, Howard Thurman. How were you influenced? What did you gain from them?

A: Much. What can I say? When you see another person praying with fervor, and you get the feeling that you attune your heart toward where a person is, and you get to see that person underneath praying. … I still remember THE BELLS OF ST. MARY, when I fell in love with Ingrid Bergman — how she was fully, totally into that prayer, and I was saying, “Oy, Yom Kippur, I want to be where she is at this point.” Or [seeing] Charlton Heston standing before the burning bush. I had that feeling, “Oy, how wonderful that would be to be in that place.” When they sing, “I want be in that number / When the saints come marching in,” that is a very real feeling. …

When I began to read about Rama Krishna and saw that there was a Hasidic rebbe, as it were, in India, when I began to read what people were describing as difficulties in mental prayer — and this was a Trappist monk who had written that book — that touched me a great deal. When I came to Boston University, I wanted to take a course in spiritual disciplines and resources that was being offered by Howard Thurman, and when I came and asked him, “Could I really trust you that you won’t want to manipulate my soul?” he said to me, “Don’t you trust Ruach Ha Kodesh?” He used the Hebrew words. That threw out for me a lot of the things about goy, and that was very, very much the point. “Ruach Ha Kodesh” means the Holy Spirit, but that he should use that Hebrew word, that was an important thing.

Q: You visited the Dalai Lama. What did he teach you?

A: That meeting with the Dalai Lama, which came about in the ’90s, had a prehistory. In 1962, when the Dalai Lama had to flee from Tibet, I sent off a telegram to Ben-Gurion and suggested that he should give him sanctuary in Israel. That never happened. I can understand why not. But then I was concerned about what will they do in the diaspora. I met Geshe Wangyal in New Jersey in 1962 and said that “I think we would be able to have something to share with you about how to survive in the diaspora.” It took about 30 years before we had this dialogue. But His Holiness was wonderfully open to this, and THE JEW IN THE LOTUS describes the whole thing.

I know what it means to live as a monk. I also know what it means to be the manager of a community. I expressed to him my compassion, really, for the role that he had undertaken and how this cuts him off sometimes from being able to do his own spiritual work. He then grasped my hand and appreciated that.

We work in different spaces, but it doesn’t mean that we do different work. We each want to preserve as much of the ethnic and traditional material that we can, but to transform it so that it can be practiced in the present. Once I see somebody like this doing it, I feel that I have greater connection with such a person than I would have even with people of my own faith who are trying to do, still, the restoration work. Matthew Fox, for instance, is a person with whom I have very, very close connection because of that. He’s doing it in Christianity, and the Vatican didn’t understand that. I see the same thing but much more hidden in Islam. There are some people. We met the Nobel Prize winner, Shirin Ebadi, a wonderful woman who wants to be able to work from within Islam. There’s another woman in Toronto at this point who is trying to create this kind of understanding. But the people who have cut off reinterpretation in Islam have gone with the Wahhabi sect, and they are the ones who have so much power.

You see that in every religion, the people to the right claim that they are the ones who need to be listened to, rather than to have a direct connection with God. They’re always afraid of spirituality because it seems to bypass their standing at — how would I say it? — the controls of things.

Q: You have written that Judaism has unique gifts to offer the world. What are they?

A: I believe that Gaia is whole and that every religion is like a vital organ of the planet. You cannot say that Earth can be alive with only the heart or with only the kidneys or with only the guts. It needs to have the whole thing. So if, for instance, I were to say, “We are the liver,” okay? (Everybody wants to be the heart.) If I say, “We are the liver,” if we’re going be a good liver, then the heart will be able to mend, the lungs will be able to mend, and so on and vice versa. If they will be able to renew Christianity or Islam or Buddhism in their own way so that it’ll be a vitally contributory element to the wholeness of the life on this planet, that’s just going to be wonderful.

What do we bring? First of all, we bring something about time. Commodity time has killed our relationship to nature. We have fluorescent lights that want to say it’s daylight when it’s night. We have temperature arrangements which make us feel that all seasons are gone now. We don’t live any more in organic time. Many calendars there are, and some can go by the sun alone. An Islamic one goes by the moon alone. But we go by sun and moon, which means that they both have influences, as if to say there’s a masculine time sense and a feminine time sense, and they work together. Passover is always at the time of the full moon of the vernal equinox. And the festival of the harvest is always at the full moon of the autumnal equinox, which means sun and moon are together.

When you understand living in organic time, then Shabbat comes in. There’s a big difference whether you celebrate the Sabbath as the seventh day or the first day. If you do it as the first day, then you say, “I’ll rest so I can work.” If you do it on the seventh day, then you say, “I worked and now I can be in being, not only in doing.” Shabbat is a very important thing, and some people have tried to obliterate it with 24/7 so that we no longer have the thing. …

The organic thing is important, number one. Second, we go to study. The way laypeople study Torah with us isn’t found anywhere else — the sense of wrestling with texts and working it through and asking, “How does this text speak to me at this time?” This is very much how we do Torah study in Jewish Renewal. I wish that people would study the New Testament the same way and then check with the Old Testament — and I’d like to say instead of “New Testament/Old Testament,” the “Younger Testament/Older Testament.” If they were to put these things together and really study … I think no Christian can fully understand what’s going on in the Gospels unless they have studied a little bit with Jews to understand what it was like to live in the time of Jesus.

I’ll give you a little example. I spent some time at a Trappist monastery in Snowmass, Colorado. Shabbat was coming [and] as for rolls and for wine and for candles they said, “What do you need it for?” I explained and they said, “Could we come and join?” It was wonderful. We had a nice Shabbat together. The next week I still was there, and they said, “Could we do it again?” And I said, “I have a condition. I will role-play Joseph of Arimathea and you will role-play the disciples of Jesus. And you will be coming to visit me in Jerusalem and we’ll have Shabbat together.” So I began. I made the prayer, the wine and the candles and so on, so forth. And then we talked about the lectionary, what we are reading, what they are reading at that point. And then I turned to them and said, “Well, what’s the Master been doing in Galilee?” And one says, “Well, we had this wedding. We ran out of wine,” and they brought [that] back into what was happening between us as Christians and the Shabbat, and everything came alive at that point. I think that’s a very important part for all of us — study of Torah and the celebration of it in time.

There is an element in the way in which we see instinctual stuff. We don’t say something is forbidden. We say a lot more: stop for a moment, become conscious. So, for instance, you want sex? Good. You make a brachah (blessing). You get married, and you raise it to a higher level. You want food? You make sure that if you slaughter an animal, you do it in the right way and then you share with other people. There is an element of that justice making in the world that we call “tzedakah.”

If you read the Torah clearly, you see that nobody could get so rich that they own everything, that they create a feudalism. And nobody can get so poor that they can’t have access to a corner of the land that’s being left for them. The sense that we have of tzedakah — I want to say, nowadays, I picked up a newspaper that had free loan things called “gemilut Hasedim,” the Hebrew for “doing of kindness.” If you want to get married and you want to have a gown, they have a whole closet full of gowns you can get. If you need to get dishes, there are a whole bunch of dishes available. If you need to have crutches or a wheelchair, they have created this whole system of being able to help people.

I wish that when they talk about faith-based charities they wouldn’t be just organizations [but] that they would do a lot more organically and communally in these things. These are the contributions we made, and people can watch us do them and participate with us and then bring it home to their situations.

We need to reconstitute and fix, if you will, that disturbance that creates life in the beginning. But it has to be made organic. It has to be harmonized. So we are told [in Kabbalah] that there are sparks of holiness and goodness hidden in so many places. The task that we have is to reconstitute these and to bring them and harmonize them together. That’s called “tikkun olam,” fixing the world.

One of the ways we do that is to ask, “What is the just, the balance of that?” At one point I wanted to create a research situation in commerce and ask people, “Tell me, when did you feel you did a righteous deal? You didn’t rip off somebody else. They didn’t rip off you. And what was the feeling that you had?” We need to create for the new market situation what is equity — the imbalance of trade and the way in which we are dealing with native peoples, indigenous peoples and paying them a small amount for what we charge a lot for and so on, so forth. There’s a lack of equity, a lack of tzedakah. And that justice element is very strong in tikkun olam.

Q: What is your goal?

A: I’m going to be 81 years old. I’m about to go into a place that’s going to be a lot more withdrawn from outer activity. I’ve worked for a while to bring consciousness to aging, and that was in my book, FROM AGING TO SAGING, to be able to help people see what to do with the later part of their life. We don’t have live models for what to do after retirement. That was an important part of my work. As long as I can connect people in a loving direction with God, the rest is up to God. Most of the time people feel as if God wasn’t there, and they have to fix everything up. I don’t feel that. What I feel is that once I have introduced people, as it were, to God and God to them, and they feel that they have a relationship which expresses them in prayer, in daily life and so on, then my job is done. I can withdraw. I would like to be able to have people think of me as having loved them to God.

There is spiritual technology that we haven’t yet learned to explore. We’re beginning to get glimpses of the crystals of water, how mind and spirit can influence that. I feel that in order to bring about peace and harmony in the world, we need to get adept at working in concert together, to work in ensemble together in order to create conditions on the higher level so that we don’t have such a clash of cultures and a clash of attitudes with each other that brings on such calamities. …

Q: Is there more you want to say about the impact of renewal on community and synagogue life, the impact on Jews who might not have ended up staying Jews?

A: Most of the people today in the world are underblessed. I want to bless people. I want to bring down blessings from God, and I want to bring up blessings from earth so that in your life you would feel that fullness that is your birthright. The planet is currently underblessed. We live on empty calories. It is really important to bless the food, to bless the relationship, to bless going in and out, to bless when you sit in the car and reflect again, “Could I do without as much gas?” and so on, so forth. That reflection is very important. I wish for our president and for our Congress to be able to start thinking in transpersonal terms. …

There was a time when Christians lived in a story they used to call the history of salvation. When a Jew lived in a story the story had an ending — Moshiach will come, the Messiah will be here, there will be peace on earth and good will for all people and so on. There is a same story in Buddhism, that Maitreya will show up, and so on, so forth. We have lost our stories, and I believe that unless we re-dream the myths that keep us alive, we are not going to be able to heal the planet. Most religions have claimed triumphalism, that when the final end will come, we’ll show we were right and they were wrong. We are in a post-triumphalist situation as we speak of Gaia and of all religions being vital organs of the planet. So here is really that collaboration and a vision and a dream of the healed world. Please, please dream a good world. If you stop dreaming the good world, you’re going to find yourself always guided by what is immediate or of bottom-line quality. You won’t think in terms of seven generations. So dream the good dream.