The Torture Debate

by David E. Anderson

After six months of stiff resistance and faced with an overwhelming and embarrassing political defeat, President Bush on December 15 reversed himself and reluctantly agreed not to veto a law banning cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment of prisoners in American custody.

The agreement caps a year of legal and policy debates on torture, but a recent stream of new revelations — the abuse (and deaths) of U.S.-held detainees, secret CIA prisons with “unique” interrogation methods, the “extraordinary rendition” of prisoners to other countries that practice torture, and the torture of prisoners at facilities run by the U.S.-backed Iraqi regime — suggests that the issue of torture is neither morally resolved nor politically settled.

The proposed law extends the torture ban to specifically include cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment of prisoners overseas (such treatment is already banned in the United States) and applies it to all civilian intelligence interrogators, including the CIA, as well as U.S. military personnel. It establishes the Army Field Manual as the uniform standard for the interrogation of prisoners.

“We’ve sent a message to the world that the United States is not like the terrorists,” said Senator John McCain, R-AZ, chief sponsor of the provision. “What we are is a nation that upholds values and standards of behavior and treatment of all people, no matter how evil or bad they are.”

McCain was voicing one of the key moral principles at stake in any consideration of the ethics of torture. But with the exception of a limited number of examples of religiously and ethically grounded criticism of U.S. policy and practice, most public debate has focused on legal rather than ethical or religious questions, and there has been little thoughtful examination of the historical complexities, nuances, and ambiguities that can be found even within religious traditions when it comes to torture.

Two days before Bush announced his acquiescence to McCain’s torture ban, Pope Benedict XVI issued his first World Day of Peace message and declared that “international humanitarian law ought to be considered as one of the finest and most effective expressions of the intrinsic demands of the truth of peace. Precisely for this reason, respect for that law must be considered binding on all people.” At a news conference releasing Benedict’s message, Cardinal Renato Martino, head of the Pontifical Council on Peace and Justice, said the pope was urging all countries that have signed the Geneva Conventions barring torture to “respect” them. “Torture is a humiliation of the human person, whoever it is,” he said. “The Church does not allow these means to extract the truth.”

In the United States, the National Council of Churches (NCC) and its mainline Protestant and Orthodox denominations sharply denounced the administration in November for its resistance to the McCain measure. An ad hoc coalition from across the religious spectrum, including evangelical Christians, Unitarians, Muslims, Quakers, and lay Catholics, told the president that the nation’s ban on torture, left confused by the administration’s post-9/11 policies, “must be restored in U.S. policy and practice.” After the McCain-Bush agreement was announced, the NCC praised the two leaders. “By taking this principled stand, President Bush reflects the views of the American people that torture can never be morally justified or legally sanctioned by the United States,” said Antonios Kireopoulos, an associate general secretary of the NCC.

Much of the torture debate continues to focus on legal and human rights issues. In part, of course, that is because the ban on torture and on cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment is written into law — international treaties such as the Geneva Conventions and U.S. laws that implement the treaties and make them applicable in the United States. Much of the Bush administration’s effort at explanation and justification has been legalistic, as well. As the now infamous “torture memos” from the White House’s Office of Legal Counsel and the Justice Department indicate, the issue never reached a discussion of the morality of torture but dwelled, instead, on how to find a legal rationale for exempting the United States from the provisions of the Geneva Conventions and the U.S. Constitution. Thus, suggest Joyce S. Dubensky and Rachel Lavery, staff members at the Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding and contributors to THE TORTURE DEBATE IN AMERICA, a new book edited by Karen Greenberg, who directs New York University’s Center on Law and Security, and published by Cambridge University Press, it is not surprising that religion has not been more dominant in the torture debate. “Modern concepts of human rights are largely defined in terms of ethics and law,” they point out. “In fact, none of the central international human rights conventions mention God or a spiritual inspiration as a basis for protecting the welfare of all human beings.”

Dubensky and Lavery argue that “shared values in world religion” can aid in finding more universal bases than law or legal principles for supporting human rights and a ban against torture. “While all religions worldwide do not identify the same theological basis for human rights, there are basic values across religious traditions that offer a powerful rationale for a shared condemnation of torture,” they observe.

At the same time, their survey of world religions — principally Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and Baha’i — notes how in the past, religious systems have justified torture as “the lesser of two evils.” The Inquisition carried out by the Roman Catholic Church, they note, is a well-known example of “how members of one religious community came to support the use of torture for what it believed were rightful ends. The Inquisition’s tortures were intended as instruments of salvation targeting Muslims and Jews and were used to identify heresy or other permutations of religious guilt, thereby saving the souls of sinners. … Many of the torturers saw themselves as performing acts of Christian charity, rooted in the Golden Rule’s mandate to do good for others.”

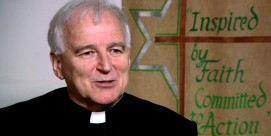

In another new book, TORTURE: RELIGIOUS ETHICS AND NATIONAL SECURITY (Orbis Books), Jesuit priest John Perry, who is also an ethicist at the University of Manitoba, notes how the Catholic Church’s position on torture has changed over time but still is not, he insists, as robustly antitorture as it should be. He cites as one positive sign of change the Jubilee Year “Confession for Commission of Sins Committed in the Service of the Church” led by Pope John Paul II at the beginning of Lent on March 12, 2000, when then Cardinal Josef Ratzinger was given the task of confessing the sin of “the use of force in the service of truth” during the liturgy.

Dubensky and Lavery also found that torture to obtain information in order to save lives has religious justification. They cite the Talmud’s emphasis on the value of each human being — “One who saves but a single life is as if he has saved the entire world” — and the opinion of Jerusalem-based rabbi Shraga Simmons that “reasonable physical pressure” could be justified to save lives, but only in an extremely rare situation. This defense of torture, widely used by administration officials, is sometimes known as the “ticking bomb scenario.” It implicitly asks whether torture would be morally justified if a suspect in custody possessed information about a hidden nuclear bomb.

That argument has been given wide currency recently by neoconservative columnist Charles Krauthammer, who responds bluntly to the “ticking bomb” scenario: “Not only is it permissible to hang this miscreant by his thumbs. It is a moral duty,” he wrote in the December 5 issue of THE WEEKLY STANDARD. For Krauthammer, that establishes the ethical principle that “torture is not always impermissible.” In fact, he argues, not only is it permissible, it should be made legal. Once deemed permissible in extreme cases, it is thus permissible in less extreme cases.

After Congress accepted his proposal, John McCain muddied the waters of the torture debate by suggesting the president could order “harsh” treatment — presumably techniques barred by international and U.S. law — to gain information from a suspect with “ticking bomb” information. “In that million-to-one situation, then the President of the United States would authorize it and take responsibility for it,” McCain said. Left unclear was what he meant by “take responsibility.” Did it mean the president was immune from the constraints of the law or, like Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights campaigners, the president would break the law but be willing to pay the price for the violation?

In a powerful rejoinder to Krauthammer, Andrew Sullivan, a senior editor at THE NEW REPUBLIC, raises in the December 19 issue of that magazine what he calls the “imperfect analogy” to civil disobedience with regard to Krauthammer’s argument that torture is permissible. “In fact, civil disobedience implies precisely that laws should not be broken, and protesters who engage in it present themselves promptly for imprisonment and legal sanctions on exactly those grounds. … They are not saying that laws don’t matter. They are saying that laws do matter, that they should be enforced, but that their conscience in this instance demands that they disobey them.”

The crux of the issue, in both the overt and the implied religious debate on torture, turns on the question of the humanity of the person to be tortured — a possible terrorist, an enemy combatant, or any of the other thousands detained in Afghanistan, Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, or the CIA’s “black site” prisons without a label, or with a very inexact one. For Krauthammer, detainees (he assumes them to be terrorists) “are entitled … to nothing. Anyone who blows up a car bomb in a market deserves to spend the rest of his life roasting on a spit over an open fire.” He is outraged that the United States gives Qur’ans to detainees: “That we should have provided those who kill innocents in the name of Islam with precisely the document that inspires their barbarism is a sign of the absurd lengths to which we often go in extending undeserved humanity to terrorist prisoners.” Leaving aside the fact that none of the Guantanamo prisoners has been convicted of killing innocents — and Pentagon reports on the abuse at Abu Ghraib have said that as many as 90 percent of those held were not guilty of anything — Krauthammer raises and rejects the essential humanity of the detainees as a moral dimension to be considered in their treatment.

Krauthammer’s view flies in the face of much religious thought as well as the secular views of classic democratic theorists. For Sullivan, insisting on the humanity of terrorists is “critical to maintaining their profound responsibility for the evil they commit.” To reduce them to a subhuman level, he writes, “is to exonerate them of their acts of terrorism and mass murder — just as animals are not deemed morally responsible for killing.” Recalling the use of torture to “save” souls in the religious wars of the 16th century, Sullivan argues that “the very concept of Western liberty sprung in part from an understanding that, if the state has the power to reach that deep into a person’s soul [and destroy their individual autonomy] and can do that much damage to a human being’s person, then the state has extinguished all oxygen necessary for the freedom to survive. … You cannot lower the moral baseline of a terrorist to the subhuman without betraying a fundamental value,” he writes.

Similarly, Perry observes that “state-sponsored torture drives a stake into the heart of human community through its violation of the human person.” A torturer “not only defaces another brother or sister, but implicitly attacks the face (image) of God in the other.”

Dubensky and Lavery make the same point in their survey of religious resources for condemning torture. “The three Abrahamic faiths … share a fundamental belief that all humans are created in the image of the one God. The torture of another person, therefore, desecrates a being created in the divine image. And this is prohibited.” They conclude: “Within every religious tradition, there are core values capable of providing the foundation for a shared perspective that all people must be treated with respect — as we would for ourselves.”

It is worth noting that for an administration steeped in the public rhetoric of religiosity and staffed with people of deep religious commitment, White House and department explanations of policy decisions about the use of torture, some still shrouded in secrecy and only partly known, have been curiously devoid of ethical reflection or moral reasoning. For the administration and for many Americans, September 11 represented a turning point in the history of the United States, if not of all humanity. It was as if history began anew. Former White House counsel Alberto Gonzales, now the U.S. attorney general, who helped to frame the Bush policies about treatment of prisoners of war, called it “a new paradigm.” Former CIA counterterrorism chief Cofer Black, testifying on September 26, 2002 about the CIA’s operational flexibility, explained it this way: “This is a very highly classified area, but I have to say that’s all you need to know: there was a before 9/11, and there was an after 9/11. After 9/11 the gloves came off.”

As constitutional law professor Richard H. Weisberg points out in an essay on “why lawyers take the lead on torture” that is included in the book TORTURE: A COLLECTION, edited by Sanford Levinson and published by Oxford University Press, apologists for torture “invoke special emergency conditions (whether spiritual or geopolitical), as though the world had never before seen such conditions. Where the premodern torturer perceived some unique threat to the soul, the modern torturer sees it to the nation-state, and his or her postmodern apologist manages to forget history in an ironic rush to cloak the torturer’s brutality in the language of utilitarianism.”

The debate this year over the McCain law and the strong bipartisan political and public support it enjoyed suggest that there is, indeed, a broad moral consensus against the use of torture and cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment of those the United States holds in captivity. But how that consensus is put into law and then parsed into policy, from definitions of torture to techniques for its employment, and whether public deliberation might still be cast in the language of religion and ethics, remains largely unresolved.

David E. Anderson is senior editor at Religion News Service. He wrote last year for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on “Ethics and the Shadow of Torture“.