In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Infant Mortality

There are large numbers of babies dying in America’s poorest neighborhoods. Ground zero for U.S. infant deaths is the poorest part of Memphis, Tennessee.

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: We take a look today at one of the country's often overlooked scandals -- the large number of babies who die in America's poorest neighborhoods. Ground zero for U.S. infant deaths is the poorest part of Memphis, Tennessee, as Lucky Severson reports.

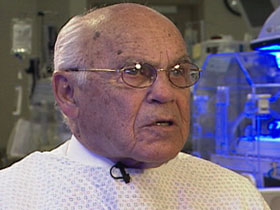

LUCKY SEVERSON: Dr. Sheldon Korones still frets over the tiny humans he calls the ultimate underdogs -- the most helpless among us. The neonatal intensive care unit at the Regional Medical Center in Memphis has treated about 47,000 premature babies since Dr. Korones founded it 40 year ago. He's proud of the improving survival rate but remains deeply frustrated.

Dr. SHELDON KORONES (Founder, Regional Medical Center, Memphis, Tennessee): I started out a man possessed, and I've remained a man possessed. Yes, the ugliness is still there.

SEVERSON: The ugliness, in Dr. Korones's view, is the infant mortality rate that plagues Memphis -- the highest rate among America's 60 largest cities. For every 1,000 babies born in Memphis, at least 14 don't survive, and most of those die within a month. In some parts of Memphis the statistics are even grimmer.

I'm standing in the middle of zip code 38108, which is one of the poorest neighborhoods in Memphis. The infant mortality rate here is four times the national average and worse than that of many Third World countries.

Tanya Clayton's first child, Justin, died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome when he was just over two months old. She had been at work. Her husband worked nights and had fallen asleep while the baby was napping. Justin was blue and stiff when Tanya found him.

TANYA CLAYTON: My first instinct was to -- I ran out of the apartment. I don't know why. But I really didn't go anywhere. I just ran.

SEVERSON: She now has a three-year-old son and a 14-year-old daughter, but she will always miss Justin.

Ms. CLAYTON: I'll never forget him, and even though he was only here a short time, he's still my first.

SEVERSON: The single biggest contributor to infant death in Memphis or anywhere, most doctors agree, is premature birth.

Dr. KORONES: If you talk about infant mortality, it's the basis of most of it, and that is a monster, no question about it.

SEVERSON: Many of the preemies here weigh under four pounds. Those born at 22 weeks and under two pounds often don't make it.

Dr. KORONES: This baby should never have been born that size. We need to keep them from coming. We want to be out of business, and we're not headed that way.

SEVERSON: The cost of a premature baby's hospital care can reach over a quarter-of-a-million dollars. A full-term healthy newborn costs a few thousand dollars.

Dr. KORONES: There are people saying that it's more expense than it's worth, yes.

SEVERSON (to Dr. Korones): You've had to deal with that?

Dr. KORONES: Oh, yes. Well, my way of dealing with it is to just go on working.

SEVERSON: Poverty is a major factor behind premature births. Neighborhoods like these, with high teen pregnancy rates, offer little or no prenatal education. Violence and the stress that comes from it is another factor, along with malnutrition.

Pastor HARRY DAVIS (St. Paul Douglass Missionary Baptist Church): Well, we're trying to educate our people by going in the streets and showing them a better way.

SEVERSON: Pastor Harry Davis and volunteer Rita Marshall canvas the neighborhood offering advice on just about everything, and especially prenatal care. An increasing number of churches and faith-based groups are getting involved. High infant mortality in Memphis is not a recent development, but it was only after a series of articles in the city's daily newspaper that officials started calling it a crisis.

RITA MARSHALL (Volunteer, St. Paul Douglass Missionary Baptist Church): We're going to talk about what happens to your body during pregnancy -- how important it is to go to the doctor, to take your vitamins, and things like that.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN (talking to Ms. Marshall): Are you all going to talk about teenage pregnancy?

Ms. WILLIAMS: We're going to talk about that...

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN (talking to Ms. Williams): Yeah, okay.

Ms. WILLIAMS: ...and that's something that we can talk about.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN (talking to Ms. Williams): ...because I have a daughter and I want her to, you know -- she's 13 and she's growing up. She's getting to the age that she is ready.

SEVERSON: One out of four teenagers in this area get pregnant, and teen pregnancy is a major factor leading to premature births. Fifteen-year-old Antoinetta Johnson lives with her two-year- old son, Jeremiah. Before she got pregnant with Jeremiah, she had dreams of doing something with her life.

ANTOINETTA JOHNSON: Sometimes, I thought about being a -- what's that thing called -- a person that do hair? I wanted to be one of them people. And then when I get grown, I wanted to go to college to be a doctor.

Dr. GREG MULLINAX (Christ Community Clinic, checking expectant mom): I'm going to feel for the head here.

SEVERSON: Dr. Greg Mullinax provides prenatal care for a 19-year-old at the Christ Community Clinic. He says many young mothers-to-be are often living in extreme circumstances, and the tension of their lives affects the health of their baby.

Dr. MULLINAX: The more that I practice up here, the more I believe that it's stressors from environment. We see moms moving from place to place, or they're just not in a safe environment. Any stressor on the mom affects the baby. So we have a high rate of pre-term delivery, and there is a higher rate of infant mortality.

SEVERSON: And many women don't get prenatal care because they lack health insurance. Brenda Johnson was four months pregnant before she got to see a doctor.

BRENDA JOHNSON: My caseworker was not very helpful trying to, you know, help me get medical insurance. And she was asking for more information needed instead of, you know, trying to help me.

SEVERSON: Dr. Mullinax says -- and he is not alone in his view -- that there is one reason in particular that there are so many premature births among African-American women in Memphis -- racism.

Dr. MULLINAX: There are all forms of racism still out there. In Memphis it's just a very big issue. One of the few things that overcomes race is Christianity, and when we talk about seeing each person as a special individual in God's sight, that overcomes the black/white issue.

SEVERSON: This is the Shelby County cemetery, where those too poor to afford headstones bury their babies. Most likely the babies here had black moms like Tanya Clayton.

Ms. CLAYTON: They wanted to charge so much for a headstone at the time. We didn't have the money, so we don't have a headstone. When I do go, they have to tell me how many steps left to step, and then I assume that I am standing above his grave.

SEVERSON: The caretaker, Robert Savage, who is also a pastor, says he tries to comfort the mothers of some of the 17,000 infants he's buried here the past 30 years.

(to Rev. Savage): What do you say to the mothers?

Reverend ROBERT SAVAGE (Caretaker, Shelby County Cemetery): Well, I - you know, I kind of pacify them, talk to them, ask them about how many kids do they already have. And some of them say, "No, it's my first one."

SEVERSON: Do any come here who say, "This is not my first one who has died?"

Rev. SAVAGE: Oh, sure. Maybe one mother might have two or three out here, you know, as years go by.

SEVERSON: Doctor Korones says he thinks there is one reason above all the others why not only Memphis but the U.S. as a whole has such high infant mortality rates.

Dr. KORONES: We're the only country in the world that sells medical care and says if you can't buy it, you can't have it.

SEVERSON: The doctor is an avid photographer. The pictures he's taken of kids around the world line the halls leading to the clinic that now bears his name.

Dr. KORONES: I see potential. For instance, these babies obviously can't take care of, look at us and say, "Please relieve my pain." And what we do here is virtually worship the potential that baby has. Right now he's almost inanimate in his movements. He's not moving much, and he's not expressing much. But we know he will.

SEVERSON: Pledging to find why so many babies die so young, the Tennessee governor has announced a new initiative and promised that "we are not going to stand aside and watch one more child die in vain."

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I'm Lucky Severson in Memphis, Tennessee.

There are large numbers of babies dying in America’s poorest neighborhoods. Ground zero for U.S. infant deaths is the poorest part of Memphis, Tennessee.